Most shale wells, regardless of lateral length, produce furiously for the first several months, then start a downward trajectory that’s accompanied by rising levels of gas and sand. This combination means that lift methods must also evolve along the well’s life.

To make that happen, three Permian Basin lift companies are advancing some existing technologies. Extract Production, an NOV company, has honed systems made to help electric submersible pumps through gas and sand issues; SPM Oil & Gas is providing stronger parts for rod pumps that deal with longer laterals toward the end of a well’s life; and Legacy Artificial Lift Solutions is also seeing rod pump updates that include much larger units, also to deal with longer laterals

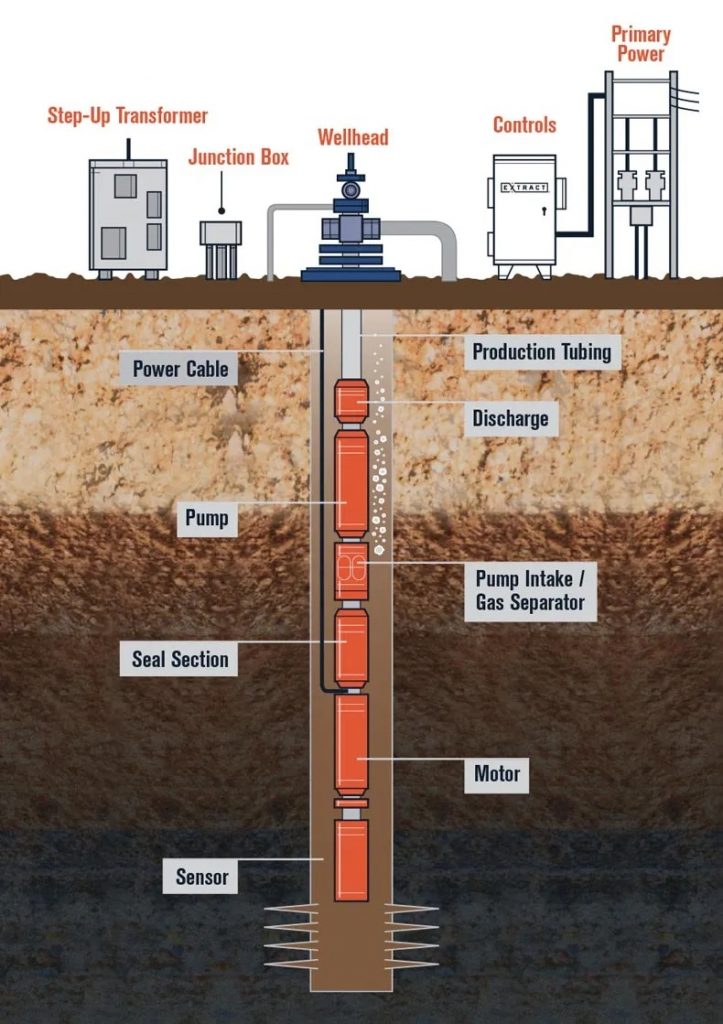

Overcoming Gas Locking in ESP

While the company’s current contra-helical pump (CHP) design is new, said Extract’s Engineering Director James Rhys-Davies, the concept has been honed, refined, and improved many times since its origin in 1997.

The current version, a 2021 redesign of a system that worked very well and now has greater durability, is designed to “plug and play” with an ESP system, Rhys-Davies said, putting it on the same motor and the CHP stages into the same pump housing as an ESP. Because it works in harsh environments, durability and reliability are keys to its success.

There are two different products, he explained. One is the 338 CHP, “which uses all CHP stages throughout the pumps and is the redesigned product in current field trials.” The other is the new XCEL Integrated Gas Processor (IGP), which uses CHP technology and sits below the pump section of the system. It is used to homogenize, separate, and compress the gas. “It has been commercial for about 18 months,” said Rhys-Davies. “We have had over 70 installations of this latest gas processing technology.”

What the CHP Does to Remediate Gas and Sand Issues

The CHP has a rotor, which is the equivalent of the impeller or the rotating element in an ESP. It also has a stator, “which is equivalent to a stationary diffuser in a centrifugal pump.” With two opposing helixes, the rotor slides inside the stator, creating two flow paths.

“The primary flow path is the big helix, then you have the secondary flow path,” Rhys-Davies explained. “That allows the pump to handle more gas and more sand than an ESP.”

An ESP’s centrifugal action flings the liquid crude to the outside edge of the pump housing, then back to the inside. As the pump throws the heavy liquid to the outside the lighter gas is trapped towards the center of the impeller, which is what causes gas locking, Rhys-Davies said.

“In the CHP you don’t get the same effect because the gas is not being flung to the outside,” he explained. “It’s not being separated; it’s all traveling in both the rotor and the stator. It’s that commingling of the liquid and gas that allows it to handle more gas in the liquid.” Because the gas stays entrained in the liquid, it doesn’t cause gas lock.

When and Where the CHP Applies

Rhys-Davies and Extract’s Vice President, Artificial Lift Product Line Chris M. Osburn stressed that the 338CHP is a niche product, to be installed as possibly the second or third replacement after a well has been in service for several months or more. “This is for more of a problem application, where centrifugal pumps with a little bit of gas handling technology don’t seem to be taking care of the problem,” said Osburn.

Rhys-Davies added, “The IGP has shown production and performance improvement, to aid conventional ESP’s in handling gas. In the more challenging gassy wells, a full string of CHP pumps has shown to provide a step change in performance.”

SPM Oil & Gas Upgrades “Red Iron” Hardware as Laterals Lengthen

Oil patch news is thick with advancements in ESPs, variable speed drives (VSDs), and other lift systems dealing with the greater demands of 2-4 mile laterals. So what could possibly be new with the steady, trusty rod pump, used by ancient Romans and seemingly little changed, design-wise, in the oil patch since the 1950s?

You might be surprised, says SPM Oil & Gas’s North American Sales Manager Scott Macfarland.

Concerning artificial lift systems, SPM Oil & Gas provides service companies and oilfield parts suppliers with production equipment, commonly referred to as “red iron” or, in Macfarland’s words, “Equipment that hangs off the top of the pump jack. Where your bridle cables extend off the front of the horse’s head there’s a carrier bar that sits between those bridle cables, which is where the main load of the sucker rod is held. We install a rod rotator there, and our polished rod clamp attaches to the polished rod at the top of the sucker rod string.”

This polished rod clamp and rotator combination must bear the load of the entire rod string while also rotating it to spread the wear incurred as the sucker rod rubs against wellbore deviations in the pumping process.

Below the horse’s head SPM Oil & Gas provides pressure-containing equipment, including stuffing boxes and the flow tee, as well as the blowout preventer (BOP). All of these components are affected by longer laterals. The rotator is affected by the extra weight and resistance of the longer rod strings needed as pumps are placed deeper in wells.

“You’re using a rod pump because you don’t have enough wellbore pressure to allow it to flow on its own. Historically, “red iron” production equipment was rated at 1,500 psi, he noted, “But it’s much more common now to see pressure ratings for 3,000 psi or 5,000 psi, or sometimes 10,000 psi. That comes from fracturing an adjacent well in a long lateral.”

SPM Oil & Gas is in a unique marketplace position, importing parts and distributing them to suppliers and service companies, Macfarland explained. While those parts are manufactured overseas, he stressed that SPM Oil & Gas’ facility in Shanghai watches over the engineering and the supply chain-procurement side to ensure quality up and down the line. “Everything is made absolutely to SPM Oil & Gas and Caterpillar Oil & Gas standards,” he said.

All’s Well that Ends Well(s)

While today’s shale-play-based oil field uses almost no rod pumps for new wells (only for the few verticals still in the mix), the trusty pump jack is still out there waiting its turn, says Stephen Floyd, CEO and co-founder of Legacy Artificial Lift Solutions. “There’s an old saying that, eventually, every well will go to rod pump.”

With drilling costs rising, most producers are in a hurry for up-front production from their horizontal wells, something that only ESPs can provide enough flow to accomplish. Rod lift is sort of like Boxer the horse in George Orwell’s Animal Farm—amazingly dependable, but very methodical.

While the demand for pumping units is indeed down from its pre-shale heyday, there is a fairly predictable cycle. Floyd said that in the “early teens” of 2013 and shortly thereafter, “the industry as a whole thought that these wells were going to need to be on submersibles or gas lift at the onset of production” for about 6-8 months before switching to rod pump. But continued development of submersibles and variable frequency drives that operate them has extended that life to several years in many cases.

Eventually, however, “They enter the decline curve and the volumes of fluid, whether it’s water or oil, decreases. Then it’s always cheaper and more economical to rod pump these wells,” he observed.

Once upon a rod pump, that connection to the well can live happily ever after. “There are pumping units pumping oil out of the ground today that have been out there for 60-70 years,” at a very low operating cost, Floyd pointed out. “If it’s maintained, the thing will sit out there until the apocalypse.”

Pumping the Updates

Even with rod pumps, there have been updates. “They’re exponentially larger than what people used to produce with here [in the Permian Basin] so you can get those volumes of fluid,” Floyd said. That relates to the longer laterals coming to vogue in the Permian and elsewhere. But the main reasons lift systems are bigger is due to the greater oil flow than simply the length of the laterals.

As with everything, cost is a major deciding factor in what pump to use when, and Floyd pointed out that ESPs are expensive in both electricity use and in repairs. ESPs often have to be replaced every few months—but of course, they’re producing a flood of oil that more than pays the cost of the replacements, repairs, and the power usage.

How’s the Rod Pump Business in the Days of the ESP?

Floyd said most of Legacy’s business is in service and repair of bearings and other parts—and they’re busy every day, along with the occasional sale of a new or refurbished pump.

The nature of the rod pump business as a whole has shifted in recent times. Floyd said the 1980s were dotted with small independent, owner-operated companies.

A wave of consolidation happened as shale plays in the Bakken and Eagle Ford opened up, but then it became a “roller coaster,” he said. “There’s a consolidation, then there’s a breakup,” just like on the production side. Today there are fewer independent rod pump companies than before, and the greatly stricter safety requirements are costly, making that a major obstacle to new small startups, he said.

It Takes All Kinds

With today’s rising production and worldwide demand, it’s apparent that the oil industry needs every type of pumping system it can find, both brand new and improved mature systems. For all types, research and development continues.

Paul Wiseman is a freelance writer in the energy sector.

Related: Lifting Well