A roustabout is, in some ways, the essence of what the oil patch is all about.

Sometimes confused by the public as a roughneck, a roustabout is generally thought of as just a less-skilled oilfield hand than a roughneck, but the fact is, their occupations are different. Roughnecks work on the rig floor, in proximity to the drillstring. They are tasked with making hole and tripping pipe.

Roustabouts handle more generalized tasks, though not necessarily easier ones. Here’s how the Schlumberger Oilfield Glossary defines “roustabout”: “Any unskilled manual laborer on the rig site. Roustabouts are commonly hired to ensure that the skilled personnel that run an expensive drilling rig are not distracted by peripheral tasks, ranging from cleaning up locations to cleaning threads to digging trenches. Roustabouts typically work long hard days.”

In my youth, I knew a few roustabouts, because my dad, Jess Mullins Sr., a drilling engineer for Texaco, knew them, worked with them, and sometimes assigned work to them. In the 1960s, Dad’s role had him working wells across much of south-central Oklahoma, operating out of Texaco’s area office in Maysville. It was in the 1960s that I first heard of Plato Andros, a roustabout who worked in that locale also.

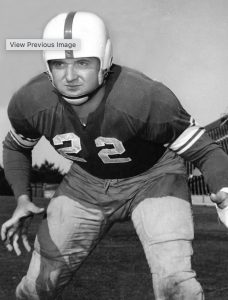

What made Andros remarkable was his past glory as a football player. An All-American for the University of Oklahoma in 1946, he had excelled on both offense and defense as a lineman. Andros would go on to play for the Chicago Cardinals—in the league now known as the National Football League—in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

At the time, though I was just a schoolboy, I marveled that someone with such a colorful history was employed as a—well, as a laborer—in the oil patch. But from what I learned of roustabouts in my dad’s day, they were not the drudges that the Schlumberger Oilfield Glossary would seem to make them out to be. They had skills, they had initiative, they had hustle and knowhow.

And they were tough, too. Andros was not the only one of their ilk to have a reputation for grit.

Roustabouts were not exactly the kind that had to be rousted about. Forget the oilfield moniker. Old time oilfield hands loved to put a whimsical label on every job they could. If a guy has to clamor around on a mast, he’s a monkey. That’s where we get the word “monkey board” for the elevated platform mounted to the outside of the mast, where the derrickman works. A welder is dubbed a “dauber.” A seismic pro is called a “doodlebugger.” A green, uninitiated roughneck is a “worm.” Anything to jibe the other guy. So they make light of some hands by calling them roustabouts, suggesting that they have to be rousted (driven, pushed) to get going. Or to be kept occupied. We’ve all heard of the phrase, “to roust someone out of bed.”

But in my own admittedly limited view, roustabouts did more than just unskilled labor, just as welders do more than “daub.”

Dad was not someone who was easily impressed. When Dad would share some anecdote about Plato and do so with a smile, I knew that Plato Andros was something special. And I knew from the stories that Plato was someone who lived life large.

The website CrimsonAndCream.com says this of Andros: “After spending more than four years fighting with the Coast Guard against Nazi submarines in World War II, he came back to Norman to finish his career with the Sooners. An outstanding blocker on offense… Dominant play on defense… A great player.”

Sportswriter Berry Tramel, in a 2010 article on the 1946 OU team, “Saluting the Greatest Generation of Sooners,” described a post-war assemblage of talent that was truly generational. Head coach Jim Tatum, a recruiter par excellance, “coached a football team unlike anything the sport has seen before or since. Four years of recruiting classes rolled into one. War-tested maturity. Unbelievable competition…. Tatum’s tryouts and practices were legendary. The toughness of those tryouts has not been exaggerated.”

The 1946 team, quarterbacked by Darrell Royal, changed OU’s football fortunes for good. It was because of the ’46 Sooners that OU-Texas weekend became the institution that it is.

Tramel quotes Norman Lamb, a lifelong Sooner fan: “If you enjoy OU-Texas weekend, thank these guys. They started it all. Thank God for these guys who survived large, underfed families, the Great Depression, the hell of World War II, and Jim Tatum’s football practices in 1946.”

Tramel goes on: “[One teammate of Andros] said the typical Sooner ‘chewed tobacco and kissed every girl.’ They were like Plato Andros, the raw-edged Sooner who was ‘rougher than a cob.'”

Plato’s brother Dee Andros was another OU football standout on that ’46 team, one who later became one of the greatest head coaches in Oregon State football history.

Most of Andros’ teammates were also veterans of WWII. The Greatest Generation. Tramel describes a few of them:

“Buddy Burris earned three battle stars fighting in both Europe and the Philippines. Ken Tipps was a bombardier/navigator on B-29s in Guam.

Homer Paine’s old football knee injury flared up in the Army; he was transferred to an anti-tank unit, where he rode instead of walked. Probably saved his life. Paine’s previous infantry unit was virtually wiped out in the Battle of the Bulge. Dee Andros was a field cook but shed his apron at Iwo Jima and was awarded the Bronze Star for heroism beyond the call of duty. Jake McAllister spent 40 months as a combat engineer fighting the Japanese. Big John Rapacz was a Marine who stormed the island of Roi in the South Pacific, digging foxholes to avoid Japanese fire. Homer McNabb spent three years as a Marine, enduring a skin burn across his back during savage fighting in Saipan and Iwo Jima. Eddy Davis was wounded in the battle of the Rhineland, tripping a Nazi land mine, and laid in various Army hospitals for six months. Harry Moore was a Marine lieutenant on the U.S.S. Idaho, earning four battle stars.”

Toughness like this, forged on battlefields or in Jim Tatum training camps, produced men like Plato and Dee Andros. Dee’s rise in the coaching ranks brought him fame and affection that lasts to this day among those who knew him. Known for racing out at the head of his team when they took the field at games, Dee, at 5’10” tall and 310 pounds, clad in a bright orange OSU windbreaker, earned the nickname “the Great Pumpkin.”

Maybe it was Plato who gave my dad tickets to the OU-Oregon State game during a time when Oregon State was flying high. I don’t know for sure. But we were at the game in Norman, Okla., and when OSU rushed onto the field, Dad pointed at Dee and (probably being informed by Plato) said with a laugh, “Dee Andros has a rule that none of his players can pass him.”

Plato was no puny fellow, either. He told my dad that during his pro football years, getting to the quarterback was not all that hard because he was so much bigger than the offensive linemen he faced. Some of them were not much over 200 pounds. Plato said he would hook his arms under theirs, lift on them, and carry them back to the quarterback.

One incident involving Plato became part of the local lore in Texaco circles. Plato and another man—I think it was another Texaco roustabout—were driving in Lindsay, Okla., when a carload of local toughs began jeering at them and making close passes to them on the road.

Plato and his companion led the harassers out of town and down a country road. When they reached a place where a steep slope dropped away from the road, Plato and partner parked their vehicle close to the dropoff, got out, and took positions back-to-back on the narrow ledge between the parked car and the slope that dropped away. Being so positioned, they could take on any assailants one or two at a time, rather than all of them at once.

On came their harassers, piling out and charging them. Whether their assailants came at them from one side or the other, or from across the roof of the car, Plato or his pal would knock the thunder out of them and/or heave them off into space, to tumble down to the bottom. They’d clamor back up, only to go flying down the slope once again. Oh, the humanity.

Plato Andros, who passed away in 2008, was well remembered by OU football faithful, but he was well remembered by the oil patch as well.

Right now, somewhere, there is a football player looking for work in the patch. Take him on. You might find he’s got some toughness. And you might just end up with a colorful character—the kind the patch is known for.

Jesse Mullins, editor of Permian Basin Oil and Gas magazine, was raised in Oklahoma and has been a Texan for the past 25 years.