The Cline Shale, still in its infancy as a producing zone, is exerting a profound effect in places like Garden City and the rest of Glasscock County.

While the Permian Basin is a busy place for the oil and gas industry these days from one end of the basin to the other, tiny Glasscock County on the eastern side of the basin is perhaps the epicenter of what is happening during the region’s most current oil boom.

While the Permian Basin is a busy place for the oil and gas industry these days from one end of the basin to the other, tiny Glasscock County on the eastern side of the basin is perhaps the epicenter of what is happening during the region’s most current oil boom.

“It is incredible,” Glasscock County judge Kim Halfmann said. “It is a mixed blessing. As a county official, I appreciate the taxable revenue [that the oil boom has brought the county]. Whether it is enough to offset the damage to our roads, I don’t know. We were a small quiet county. Now, we have people coming in and out and up and down. I worry about our kids who are just getting their driver’s licenses being out on the road.”

To get an understanding of the challenges that Halfmann is facing with the current oil boom, consider these facts:

Glasscock County is a rural county just south of Big Spring in Howard County and east of Midland County. It has a population of only 1,220, according to Halfmann. Garden City, the county seat, is unincorporated. It has only one convenience store (that she said is doing a booming business) and no restaurants, although a portable taco shop and a few burrito wagons have popped up to accommodate the increase in oil field workers, according to Halfmann.

“A couple of RV parks have opened,” she added, “but we don’t have any man camps in the county. Every little nook and cranny has an RV on it, though.”

Halfmann said Glasscock County has averaged 36 to 40 rigs actively drilling in the county over most of the last year. When one considers that at least 40 or 50 workers will usually set foot on the well site during the drilling of a well, one can readily do the math and realize that there are more people working and driving back and forth to the rigs every day than actually permanently live in the county.

There were 90 new drilling permits filed for Glasscock County in December and 75 more in January. Both figures were the most filed for any county during those two months in the Permian Basin. A total of 78 new wells were spud in the county in the final month of 2012 and the first month of 2013 alone. In all, there are 2,465 producing wells in Glasscock County, according to the Texas Railroad Commission’s most recent statistics, a figure that represents twice the county’s population.

To deal with increased crime rate that comes with additional people in the county, Halfmann said Glasscock County has added two deputies to its sheriff’s department.

“One of the biggest problems with traffic is overweight trucks—trucks that don’t meet the law,” she explained. “The big companies aren’t a problem, but the smaller, fly-by-night companies are a big problem. They own a water truck and they send it to Glasscock County. Our county roads are taking a beating. Our accident rate has increased more than 500 percent.”

Halfmann said there is some relief coming for the county’s main thoroughfare, Highway 158, which runs from Midland through Garden City to Highway 87 just north of Sterling City.

“We are working with our legislators,” she stated. “They know we are in trouble.”

She said the Texas Department of Transportation has already approved funding to turn Highway 158 from a two-lane to a four-lane highway from the Midland County line to Highway 33 in Garden City.

“And we are also waiting on final approval for funding to make Highway 158 a four-lane from Highway 33 to Highway 87 in Sterling County,” Halfmann continued, “so that means Highway 158 will eventually be four-lane all the way across Glasscock County. We now have our first traffic light in Garden City, too.”

Halfmann said one of her major concerns is the county’s volunteer emergency management service and volunteer fire department.

“We have only a volunteer EMS. They are the best in the business,” she claimed. “But now with the influx in people and increase in traffic, there is more pressure on the volunteers. I worry about burnout. We are seeing a huge increase in calls that are taking our volunteers away from their regular work.”

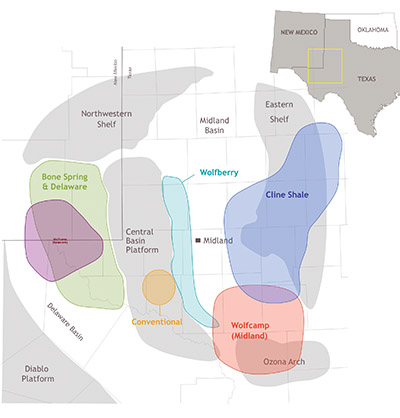

One thing that makes Glasscock County unique is that it has been the center of not one but three distinct plays during the current boom. Halfmann, who took office on April 1, 2010, said the oil and gas industry has been thriving ever since she took office. First, there was the Wolfberry play when the industry started commingling the Spraberry and Wolfcamp zones, along with deeper formations with deep vertical wells in which each zone receives separate fracs. Glasscock County is at the heart of the eastern flank of the Wolfberry play, which is credited with igniting this most recent surge in activity in the Permian Basin.

Then, Laredo Petroleum became the first company to start drilling horizontal wells in the Wolfcamp formation in Glasscock County. And now, the much-anticipated Cline Shale play is taking off with many of the initial wells being drilled in Glasscock County.

“We are just now seeing fewer land men in the county courthouse,” Halfmann explained. “They came back in because the Cline Shale is a separate play from the Wolfberry.”

She said county judges, city mayors, economic development directors, and chamber of commerce officials from all across the Permian Basin met April 2 at the Horseshoe Arena in Midland to discuss the impact of the oil and gas industry, to forecast needs in infrastructure and to receive a legislative update, all in an effort to anticipate and meet the challenges brought on by the industry’s boom.

It is easy to see the remarkable growth in Midland and Odessa that has been generated by the oil and gas industry’s increased activity. But the current oil boom is being felt, too, in even the most rural counties of the Permian Basin, bringing not only increased growth but also problems associated with more people and more traffic. Perhaps no county is experiencing that impact more than tiny Glasscock County.