With prices up, Basin natural gas production sees new life.

By Paul Wiseman, special contributor

Discussing natural gas in the Permian Basin is somewhat like talking about Pippa Middleton—a lovely idea but not really the main attraction. The three Texas Railroad Commission districts that primarily identify the Basin—7C, 08 and 8A—accounted for 441.1 thousand MCF of gas from gas wells in 2012, a figure that falls short of the comparable statistic for Tarrant County, the state’s leading single county in gas production, which brought forth more than 819 thousand MCF in the same time period.

Most of the strictly gas wells in the Basin are in the Delaware Basin in Reeves, Ward, and Pecos counties, along with the Bone Spring play along the Texas-New Mexico border south of Carlsbad. Wolfberry gas production (with Natural Gas Liquids, or NGLs), however, is on the upswing. Much gas in the area is a byproduct of oil wells, which sometimes makes it as much a nuisance as a product.

Still, CH4 is and has been a significant contributor to the area’s energy production and its economy. And, after a time of low commodity prices due to production increases that culminated in a storage glut in the fall of 2012, prices may be poised to make a comeback in the near future.

Certainly they have regained ground in recent months.

In an article that appeared April 24 on Fox Business (foxbusiness.com) entitled “Rise of Natural Gas Prices an Enigma,” writer Dunstan Prial observed that natural gas futures “are up 26.5% year-to-date.” And in that same week, he observed, “futures contracts for May delivery were trading at $4.189 per thousand cubic feet on the New York Mercantile Exchange. A year ago, increased production and unseasonably warm weather reduced demand and pushed the price for the same contract below $2.”

The price bump this spring, reaching over $4 per MMBTU for the first time in over a year and a half, can at least in part be attributed to the working off of that oversupply, according to Mike Banschbach, a Midland natural gas marketing consultant.

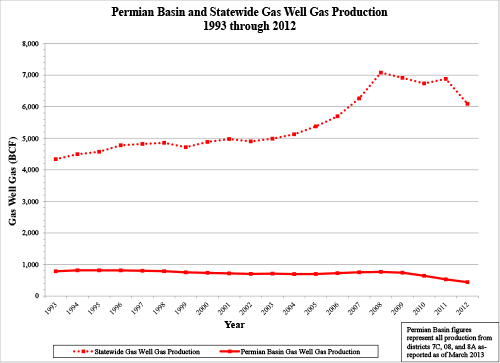

If the prices were to shoot up to $5-$6 per MMBTU in the near future (which he is not predicting) there is much more gas waiting in the wings to be drilled for and brought to market, Banschbach speculated. Indeed, with prices just up to $4, Permian Basin gas production in the first two months of 2013, the latest period for which the Railroad Commission has numbers, is already at a rate that would put the gas numbers higher than last year. Still, those numbers are much lower than they were in 2010, when gas prices were above $4.

Should that happen, Banschbach mused, there could be another gas glut leading to a new drop in prices.

As Fox’s Prial observed, “It’s not as if supply of natural gas has dwindled. To the contrary, production surged in the past year as the drilling method known as frac’ing took off. Energy analysts predicted frac’ing at massive new natural gas fields… will keep supplies abundant for years to come…. In any event, some traders believe the price of natural gas is likely to level off soon or even reverse course temporarily if for no other reason than the price of has risen too high for too long.”

Of course, that is only some traders, not all.

For now, a series of late spring cold fronts harassing the eastern United States and creating greater need for heating could be part of the reason for higher prices.

While the extended period of low prices over the last 18 months has led to more entities such as electricity generation and vehicle fleets to switch to gas, most of the switching that is likely to happen has already been done, in Banschbach’s view, so higher prices are not likely to come from that direction.

According to the Energy Information Administration, increased cost of production could cause prices to firm up at $4 and begin a long, slow rise to the $8 region by 2040. The EIA’s Annual Energy Outlook for 2013 states, “As of January 1, 2011, total proved and unproved U.S. natural gas resources [total recoverable resources] were estimated to total 2,327 trillion cubic feet. Over time, however, the depletion of resources in inexpensive areas leads producers to basins where recovery of the gas is more difficult and more expensive, causing the cost of production to rise gradually.”

One challenge to natural gas production in the Permian Basin is a slowdown in processing of NGLs at plants in Mont Belvieu, creating a pipeline glut. So, Banschbach explained, companies can’t produce natural gas without a place for their NGLs to go. “If you can’t get rid of your natural gas liquids, then you cannot bring gas from the wellhead into the plant. Then the producer has the choice to either shut the well in or keep the well flowing, produce the oil, and flare the gas.”

NGL delivery had just come out of a time when all those pipelines were full and waiting for new ones to be built. So transportation can be an even bigger factor than price in the production of gas in the Permian Basin.

Keeping gas production high in the era of increased dependence on shale formations requires continued drilling activity. Many shale gas wells see a steep decline within six months, which can affect the profit or loss possibilities dependent on price. Many others, however, produce well beyond the level needed to pay for the cost of the well. Banschbach noted that, while this is a concern for gas-only wells, much Permian Basin gas is either a byproduct of an oil well or is rich in NGLs, which means that anything a producer makes on gas is a bonus anyway.

If producing shale gas were not profitable overall, companies, especially those that are publicly traded, would not keep doing it over the long haul, Banschbach said.

Part of the issue of profitability revolves around the number of frac stages needed, and, for a while, there seemed to be a competition to see who could have the highest number of stages in a well. If 10 stages are good, 20 must be better, the thinking went. Now producers are backing up and better evaluating the number of stages that actually provide the optimum production.

With all the excitement surrounding the possibilities in the Cline Shale on the eastern edge of the Basin, the question arises as to what that formation’s natural gas yield might be. At this point, however, gas and oil details are sketchy. One noted natural gas producer, Devon Energy, said they are not looking for gas in that formation. Banschbach said most producers in that area are “wanting to keep everything pretty close to the vest.” Much acreage is already under lease in Sterling and Mitchell Counties, but it is too early in the process to know very much about what is actually there.

Natural gas is certainly no longer looked at as a nuisance, although the flares that turn the night sky orange verify that it still is not the primary focus. But as the nation looks for cleaner-burning fuels for electricity generation, transportation, and other needs, gas continues to grow in importance, even where it is only second fiddle to oil.