Remediation–the remedying of oil spills and other oil and gas mishaps–is an industry unto itself, and one that makes great sense for companies wanting to protect the bottom line and maintain a squeaky clean image to boot.

by Hanaba Munn Welch

Don’t cry over spilt oil. Remediate it.

“Remediation,” in the context of oil and gas production, is a fancy word for “cleanup.” Remediation is required when pollution occurs. In some situations, operators themselves can manage remediation; in other cases, it takes someone with a license to get the job done. Either way, it’s the law, and a whole cadre of people who specialize in remediation cater to the needs of oil and gas operators, some in very sophisticated ways.

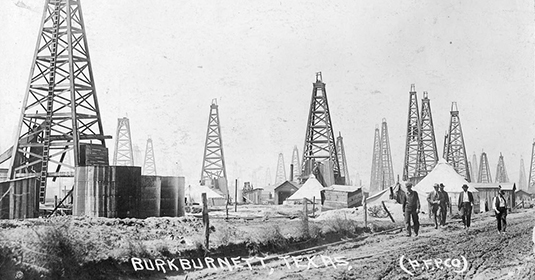

It hasn’t always been so.

In the context of history, remediation is a relatively new aspect of oil and gas production. Remediation reflects society’s current emphasis on environmental concerns. Mankind has been utilizing petroleum products at least since Noah sealed the ark with pitch. But references to the remediation of pollution created by pitch, bitumen, asphalt, or other naturally occurring petroleum products in the ancient world are hard, if not impossible, to find. (So are examples of remediation of other kinds of pollution and offenses against nature, not that the problems weren’t recognized. To wit, consider the deforestation and resulting erosion so aptly described by Plato in his Critias.)

Fast-forward to the first half of the 20th century. Neither the word “remediation” nor the concept thereof is to be found in 386 pages of text nor in the appendices, tables, and index of the 1940 first edition of the book This Fascinating Oil Business by the late Max W. Ball, who purported to cover all aspects of the industry from its earliest known inception right up to 1939. In the book, Ball comes closest to the sort of ethical considerations that underpin remediation when he talks about reducing waste, specifically when he lauds refinery research chemists who in his day and time were finding ways to derive new products from oil, to a great extent “from by-products that formerly went to waste or were burned as refinery fuel.” But it’s the economic benefits of cutting waste—not the moral aspect—that Ball extols. Not to say he didn’t see a moral obligation for the oil industry to conserve resources and respect the environment, even to repair it via remediation. He just doesn’t write about any such moral obligations or procedures. Such topics would have taken him on philosophical rabbit trails away from his main topic. By contrast, any survey of the oil industry today would be remiss not to mention remediation and other disciplines that fall in the environmental category. It’s part of the business.

But if remediation by any name existed in 1939, it seems not to have been of general interest. Even the word “environmentalist” meant something different in the first half of the 20th century, referring to the school of thought that people were more a product of their environment than their genetics.

Not until the 1960s did the word “environment” and its derivatives begin taking on the current meanings and connotations that refer to the art of protecting the natural world—in short, “saving the planet.” Equally imbued with the new morality, at least in the oilfield, is the word “remediation.” After all, it sounds better than “cleanup,” which makes it sound like a mess has happened, even if it has.

That said, “Operator Cleanup Program (OCP)” is the name of Texas Railroad Commission (RRC) program that oversees remediation of oilfield sites. The OCP falls under the RRC’s organizational rubric “Remediation/Environmental Support.”

Remediation/cleanup is the responsibility of the operator, but, depending on the level of complexity, the task can require someone licensed as a professional geoscientist—a geologist, geophysicist, or soil scientist. Often the critical factor is the location where the incident occurs. Protecting groundwater is a primary objective.

In today’s oil and gas world, where oil spills and other environmentally unfortunate events can lead to expensive fines, companies have become hyper-sensitive to the idea of environmental damage and to the costs inherent in the same. And they have shown that they are quicker to take advance cautions and quick to seek remedies when their cautions have proven insufficient. It’s good business to stay on top of such things and it’s good corporate citizenry to be pro-active in such matters where lapses can hurt the industry on the whole.

Geologist Mark Larson is president of Larson & Associates, Inc., a Midland-based firm that provides environmental consulting services as well as geospatial information management. In the environmental realm, investigation and remediation are services the company provides.

In one sense, Larson’s company mixes oil and water, depending on both to exist. But initially it was his interest in water that drew him into environmental services. “My main goal coming out of college was to work in the field of groundwater,” he said.

Now, with 25 years in the environmental field, he’s involved in a range of services that have been steadier than the ups and downs in the oil industry per se. His company provides services that go hand-in-hand with oil production and translate into assignments all over the state and elsewhere, notably Utah and Colorado. It’s the nature of remediation that water is a concern.

“As a consulting firm, we provide services other than groundwater,” he said. “I just like the groundwater side of the business.”

In Texas, the work can be in East Texas, the Fort Worth Basin, or the Permian. “It’s pretty much statewide,” Larson said.

Like oil and gas operators, Larson and others of his ilk aim to meet the dictates of the Railroad Commission. “The Railroad Commission has primacy in Texas with regard to remediation or cleanup,” he said.

In some situations, an operator doesn’t have to involve a professional firm like Larson’s to effect a cleanup, but when professional expertise is required, a side benefit also results. “It gives them [the oil and gas operator] an unbiased third-party opinion,” he said.

The air is another area of concern regarding pollution from oil and gas production. “Depending on the amount of emissions they have, they can be required to permit their emissions,” Larson said. “Often it comes down to the amount of material you are emitting.”

Tank batteries, gas plants, and refineries are the operations generally under scrutiny in the realm of air pollution. Scrutiny in a broader sense is one thing the Railroad Commission does, partly via field inspectors.

But whether anyone’s watching or not, reporting significant spills is the responsibility of the operator. “If it’s a minor spill, it may not be reportable,” Larson said. “In that case, an operator may go ahead and elect to do the cleanup. If it’s a reportable quantity, then you have an obligation to report it to the Railroad Commission.”

Statewide Rules 8, 20, and 91 set remediation standards and are summarized by the RRC in its Filed Guide (posted online) for the Assessment and Cleanup of Soil and Groundwater Contaminated with Condensate from a Spill Incident.

Rule 8 essentially prohibits pollution of surface and subsurface water.

Rule 20 requires that fires, leaks, spills, and breaks be reported immediately.

Rule 91 deals with crude oil spills in both non-sensitive areas and in sensitive areas and with hydrocarbon condensate spills in general.

Various factors come into play whatever the spill, particularly when groundwater is at issue. Not only does the type of spill make a difference but also the type of groundwater put at risk.

Sometimes remediation refers to a relatively simple cleanup—essentially, capturing all free oil and cleaning up any contaminated soil.

In other cases, specifically a condensate release, laboratory analysis of samples is required to determine levels of total petroleum hydrocarbons and also benzene, toluene, ethyl benzine and xylenes (BTEX). Soil-to-groundwater protection limits are also at issue.

As for groundwater, the RRC provides differing guidelines depending on three different classifications of the water resources, based on both the quality and quantity at stake.

Sometimes remediation can be as straightforward as mixing good soil with contaminated soil and tilling the mix to allow decontamination to occur naturally via aeration. The process is called landfarming. The RRC classifies landfarming as “bioremediation”–another relatively new word in the scheme of things.

But in an industry that, to its credit, is constantly developing new ways to meet new needs, new words are an inevitable byproduct of refining the jargon.