By Joe W. Specht

Don’t forget to click on the songs to hear the music on YoutTube.

Freddie Frank, Slim Willet, and Wayland Seals penned and performed some petroleum-revering refrains.

Editor’s Note: It might come as a surprise, this revelation that the oil business has had a musical genre all to itself. Surprising or not, the oil patch has inspired songwriters and musicians for decades, and they’ve left behind a legacy. In our six-part series, we’ll explore the Permian part of that legacy—a tale with as many ins and outs, ups and downs, dreamers and schemers, as the oilfield itself.

Since the first major West Texas discovery of oil in 1923 in Reagan County with the Santa Rita No. 1, the Permian Basin has been synonymous with oil and natural gas, a circumstance that has spawned an energy culture that affects the lives, directly or indirectly, of most West Texans. Ford Turner, a pioneer oil scout, described the area with fitting superlatives as having “the greatest distances, the largest fields, the shallowest gushers, the biggest production, the greatest potential, the deepest wells, the largest tank farms, the longest pipe lines, the most expansive operations.”

It should comes as no surprise, then, that the region eventually produced some petroleum-related songs—songs recorded commercially, intended for sale to the record buying public. Written by professional wordsmiths and roughnecks alike, these musical narratives speak to life in the oil patch as well as to the continuing social and economic impact of the industry itself, a fact still often ignored by folklorists and music historians.

There is no better example of a singer-songwriter who turned to the petroleum industry for inspiration than Abilene, Texas’ Slim Willet, the composer of the 1952 million-selling “Don’t Let the Stars Get in Your Eyes.” In fact, his first recording in 1950 for Dallas-based Star Talent Records was “I’m a Tool Pusher from Snyder,” and it proved to be a popular seller in West Texas. “Hadacol Corners,” the flipside of “Don’t Let the Stars Get in Your Eyes,” paid homage to Hadacol Corner (now Midkiff), the tiny crossroads community in Upton County. And continuing references to the Permian Basin can be found on his 1959 album, Texas Oil Patch Songs by Slim Willet (Winston LP 1040). (For more on Willet, see Joe W. Specht, “I’m a Tool Pusher from Snyder,” Southwestern Historical Quarterly, January 2010).

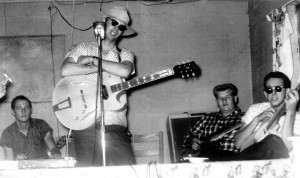

Another perennial West Texas favorite is Freddie Frank’s “This Old Rig” (Permian PO 1001), which dates to 1957. Frank (often misspelled “Franks”) arrived in Odessa in 1956, and he continued to be a staple of the local music scene for the reminder of the 20th century. Born Frederick William Frank in Baton Rouge, La., in 1931, Freddie was one year old when his father, an oil field machinist, moved the family to Kilgore, Texas, in Gregg County. Here the youth grew up surrounded by the derricks and pipelines of the giant East Texas oil field that sprawled across Gregg, Rusk, Smith, Upshur, and Wood counties.

Adroit on both fiddle and guitar, Frank began his professional music career at the age of 17. In the early 1950s, Freddie occupied the fiddle chair in the house band at the Reo Palm Isle in Longview; he waxed singles for Abbott Records in 1952 and Starday Records in 1953; and he hooked up with Jack Rhodes, a songwriter, producer, motel owner, and bootlegger in Mineola. Rhodes, who is credited with such standards as “Satisfied Mind” and “Silver Threads and Golden Needles,” utilized Freddie’s songwriting and arranging talents. As Frank recounted to Texas music historian Andrew Brown, “I’d write the tunes for ’em. Make ’em meter out, and doctor ’em up.” Gene Vincent and the Bluecaps recorded two of their collaborations—“Five Days, Five Days” and “Red Blue Jeans and a Ponytail.” Intent on furthering his own career, Freddie in 1956 decided to head west to Odessa, Texas. The timing couldn’t have been better.

Odessa, the county seat of Ector County, was already the oil field equipment service and supply center for the area and home base to a workforce of drillers, welders, roughnecks, and the like. Recognized as “the world’s largest inland petrochemical complex,” Odessa had a population would grow from 29,495 in 1950 to 80,338 in 1960. With the boom in full swing, area nightclubs, honky-tonks, and roadhouses did a steady business with live music as part of the mix. Frank quickly took advantage of the situation: “You couldn’t make any money there [in East Texas]. We were playing in those damn clubs for seven and eight dollars a night. And then, we come out here and we’re making $150 a week. That was pretty good money for a musician. It’s always been easy to find work and make a living out here.”

And make a living he did. Freddie became a familiar presence at such Odessa night spots as the Silver Saddle, Melody Club, The Stardust, and Ace of Clubs. He played fiddle with Tommy Allsup and the Southernaires and Bill Myrick and the Rainbow Riders, toured briefly with the Miller Brothers Band, and worked with Hoyle Nix and his West Texas Cowboys. He even owned his own club, the Hawaiian Club, and started a record label with the area-catchy moniker Permian Records. In addition to releasing three singles on Permian Records, Frank also recorded with Billy Thompson and the Melody Cowboys and Bill Massey and the Lone Star Cowboys. In the late 1960s and 1970s, Freddie Frank and the Volunteers held down a weekly residency at the Cow Palace Supper Club; in the 1980s, he played fiddle in Ben Nix’s band in Big Spring.

On occasion, Frank left the music business for other jobs: “I roughnecked… I’ve strung telephone lines, pipelines… tried my hand at everything, but wound up coming back to playing the fiddle.” In fact, the idea for “This Old Rig” came to him while he was employed as the jailer for the police department in Farmington, N.M. Freddie recorded “This Old Rig” in 1957 at the Ben Hall Studio in Big Spring for release on Permian Records. As he told Andrew Brown, “[The song] was a parody on [Stuart Hamblen’s] ‘This Ole House.’”

Stuart Hamblen had roots in West Texas, too, but he made his name in Southern California in the 1930s as singer, songwriter, recording artist, radio personality, and B-Western actor. In 1954 while on a hunting outing in the Sierra Nevada Mountains, Hamblen found the body of an aging prospector who had died in a ramshackle cabin. The scene prompted Hamblen to pen “This Ole House,” a million selling Number 1 hit for Rosemary Clooney the same year. The toe-tapping melody creates a gospel revival mood with the lyrics drawing comparisons between the ‘ole’ house and the human body, emphasizing life’s temporal nature with just rewards awaiting in heaven.

Frank retained the melody and word play of the Hamblen original, substituting imagery straight out of oil patch culture, as his roughneck chronicler lists a litany of troubles besetting the drilling operation. First, the rig is populated with “a bunch of weevils, and they don’t know what to do.” In this case, a weevil, or boll weevil, is oil field lingo for a new, unseasoned employee. To complicate matters, the driller is aging and accident prone: “His drillin’ days are over, ain’t gonna run the rig no more/He done made up his time when the [crown] blocks went through the floor.” If that weren’t enough evidence of ineptitude and inexperience, well, the “location’s full of junk iron, and the hole’s off ten degrees.” Although the locale isn’t identified, it could well be Canada or Alaska, because the hands, who “are all from Texas,” have to endure temperatures of “forty-nine below.” In addition, the narrator’s car is “a total loss” from driving to and from the drilling site on rutted roads. The chorus sums up the general sense of frustration:

Ain’t a-gonna need this rig no longer, ain’t a-gonna need this rig no more

Ain’t got time to paint the drawworks, ain’t got time to wash the floor

Ain’t got time to oil them motors, or to fix the spinning chain

Ain’t a-gonna need this rig no longer, I’m a-gettin’ ready to make a change

Rather than consoling himself with thoughts of a better life in the hereafter, the roughneck finds his comfort in dreams of the Lone Star State. Still, he hasn’t lost the perpetual optimism that is such an essential ingredient of oil field exploration. Consequently, it’s not time to pull up stakes quite yet but rather to resolve, “I’m a-goin’ back to Texas soon as I make one more hole.”

“This Old Rig” received airplay on area radio stations. Freddie dispatched the record around the world: “We sent ’em to Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Alaska, Australia… anywhere there was an oil patch. We made quite a bit off it, but it all dribbled in and dribbled out. We sold those things for eight years.” Al Dean of Freer, Texas, and “Cotton Eyed Joe” fame also recorded a version. Appropriately enough, a copy of the Frank 45 rpm disc now resides in the archives at the Petroleum Museum in Midland.

In 1960, Frank turned to the Slim Willet song bag for a two-sided follow-up: “Haywire Jones” backed with “Tool Pusher on a Rotary Rig” (Permian PO-1004). “Tool Pusher on a Rotary Rig” is a re-titled version of the 1950 Willet regional favorite, “I’m a Tool Pusher from Snyder.” “Haywire Jones,” the story of a wildcatter with designs on striking it rich even if has to “drill clear through to China,” first appeared on Slim’s Texas Oil Patch Songs album. Unlike “This Old Rig,” the Willet coupling failed to attract much attention.

Wayland Seals is perhaps best known as the father of Jimmy Seals (of Seals and Croft fame) and of Dan Seals, who made his mark first as “England Dan” of England Dan and John Ford Coley and who furthered his career as a solo act in country music. Wayland was born in 1912 in Big Sandy, Tennessee; his father, Fred Seals, moved the family to Eastland County in 1919 “because there was work in the oil fields.” Both Ranger and Desdemona were awash with crude. Fred Seals found employment as a pump manager, or pumper, whose duties included operating and maintaining the oil well pumps on a company’s lease. Wayland eventually followed his father into the oil patch life. During World War II, he served as a warrant officer in the U.S. Army. Upon discharge, Seals headed to West Texas, settling near Iraan in Pecos County, where he took a job as a pipefitter for the Shell Oil Company in the prolific Yates Field. He remained in the area, living primarily in Rankin, for the rest of his life.

Music was ever-present in the Fred Seals’ household. Fred played banjo, and he taught his son the basic guitar chords. Wayland in turn passed his musical interests on to his sons. Jimmy won the Texas State Fiddle Championship in 1952, and he and his father often entertained at the Charles Chandler Ranch in Terrell County. In 1956, the younger Seals joined Dean Beard’s band, the Crew Cats, on tenor sax. Dash Crofts was the band’s drummer. At the time, Beard and the Crew Cats were recording for Slim Willet’s Edmoral and Winston Records, in addition to serving as the house band for other Winston artists.

Wayland Seals’ day job in the in the oilfield did not interfere with his own musical ambitions. He earned the reputation as a topnotch guitar picker, and he worked with Tex Collins and the Tom Cats, while also fronting the Oil Patch Boys as well as the Seals Family Band, which featured a four-year-old Danny on doghouse bass. Wayland also served as the opening act for such nationally known performers as Ernest Tubb and Bob Wills when they toured the area.

In 1957, the 45-year-old Seals, through Jimmy’s connection with Beard and Willet, made his inaugural recordings on Winston Records, and he didn’t hold anything back. When I’m Gone”/“I’ll Walk Out” (Winston 1016) by Wayland Seals and the Oil Patch Boys (Winston 1016) by Wayland Seals and the Oil Patch Boys is dominated by Wayland’s driving flattop guitar styling on a six string Gibson J-200. “When I’m Gone” is now highly prized by rockabilly pursuers.

The next year Seals returned to wax a second 45 for Willet and Winston: “Oil Patch Blues” and “I’ll Be Happy” (Winston 1024). With the petroleum industry in the Permian Basin operating at full tilt, “Oil Patch Blues” is far from a lament, capturing instead a sense of buoyant expectations. Years later, Jimmy Seals still remembered the stretch of US Highway 67 from McCamey to Big Lake “looking like a forest because of all the drilling rigs.”

Listen everybody while I tell you the news

A new song playing called the “Oil Patch Blues”

Oh me, oh my, it’s the “Oil Patch Blues”

I’m telling you, baby, they’re rocking to the “Oil Patch Blues”

What make this session truly extraordinary, though, is the Crew Cats are sitting in, which provides Wayland and Jimmy a unique opportunity to record together. Unlike his initial Winston single, which aside from Wayland’s slick guitar picking, is hardcore hillbilly, “Oil Patch Blues” furnished another example of the country-rock hybrid that was so popular in the Southwest in the late 1950s. Written by the elder Seals, the song even tosses in the ‘R’ word—rockabilly: “With a double beat of rhythm and rockabilly, too/It’s sweeping the country like a wild-eyed blues.” Father and son are inspired, with Wayland exhorting, “I’m telling you baby, they’re rocking to the ‘Oil Patch Blues,’” and Jimmy responding on tenor sax with hooting, unhinged riffs.

Joe W. Specht is at work on Smell That Sweet Perfume: Oil Patch Songs on Record, a project focusing on commercially recorded songs with petroleum-related themes as sung/written by performers with roots in the Gulf-Southwest. If you have a song that fits, contact him at jspecht@mcm.edu.