At the March 17 luncheon of the Permian Basin Petroleum Association, the luncheon speaker was Mr. James LeBas, former Chief Revenue Estimator for the Texas Comptroller’s Office and currently a tax and fiscal consultant. What follows is a transcript of his talk.

[Editor’s Note:] PBOG Magazine attended this luncheon and prepared this report. Mr. LeBas, after his introductory remarks, began by establishing how much oil and gas means to the state of Texas. He outlined the industry’s impact on personal income for residents of the state.

Oil gas pays more than double [pay of] the average job in Texas. In addition we’ve got a lot of people who receive mailbox money. Courtesy of y’all. Maybe including some of y’all who we call royalties. We’ve got an estimate from the Texas Royalties Council that states that around 570,000 families receive some kind of royalty from an oil and gas company. That’s over $16 billion a year that they’re receiving. If you do the computation, it’s not near as much per household as having a job in oil and gas. It’s around 20 something thousand dollars for a household, which is not enough to get rich on, but it is enough to put a kid through college or to buy a gently used Ford F150.

As for royalty owners, a very important part of their income comes from oil and gas, and it’s an important part of local economies. Guess what they do with their royalties? They spend them locally.

Now, does anybody remember the Great Recession? The one that happened when Obama got elected? Did we forget all that? I think we did, because of what you all did during that time. In 2008 we had the inauguration of the current president, and everything just started falling apart. Whether it’s obvious from anything he did or not. It’s on his watch.

In Texas the recession was greatly moderated by what the folks in this room were doing. Now you can see we did have a drop [in 2009] in the upstream sector. That was altogether made up within about 2 years. We hit an all time high in 2014, right in I think December of 2014, in the upstream sector. 305,000 jobs in that business.

I’m also showing the downstream jobs and the green line. You can see something really happens in that business. It’s been bobbing around 120,000 jobs for 10 years or so. It’s dominated by chemicals and refinery pipelines, that sort of thing. Never changes that much. The upstream is quite volatile. We have since the peak of the market lost over 60,000 jobs. I did a little cheat on this one statistically, adding 2 different data series together, but you get the idea. When we get the data from February, I’m afraid it might be worse still. We’re still at a great high level of employment compared to what we were. We got the bust of 2009. The trends do not look promising.

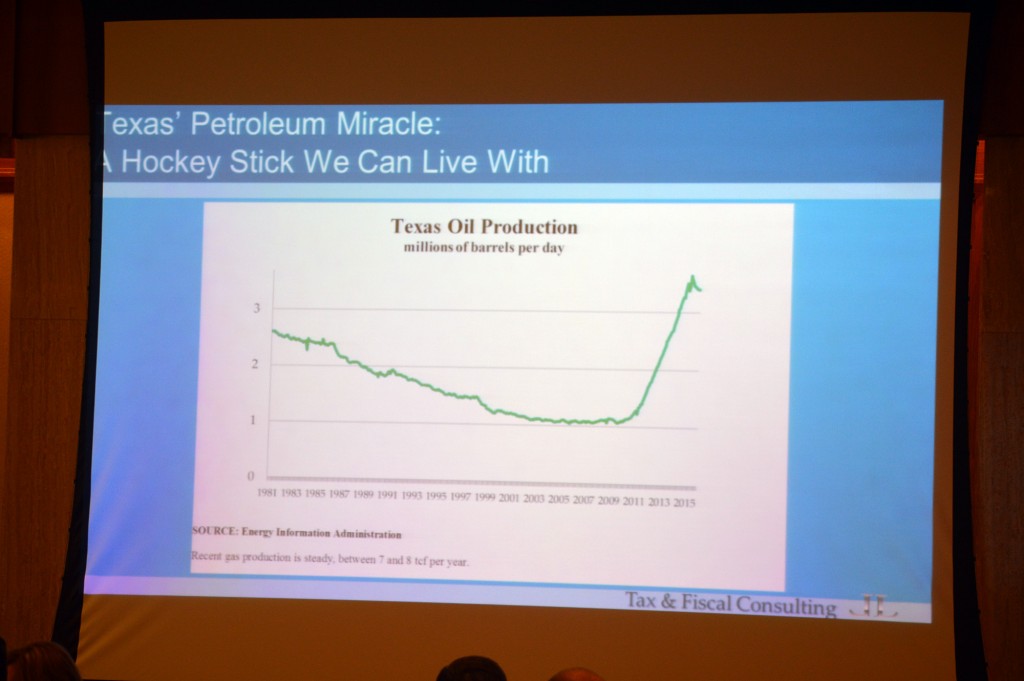

Now, I’m going to spend a little bit of time on this graph. I want to call attention to oil production. This is about a 30-year view of what happened in Texas oil production, so going back to 1981. When I got hired on by [inaudible 00:03:00] it was in that bad period in the early 80s. State control of oil. It was an early estimate. Oil production was the easiest thing in the world to forecast. Because you know what you did? You just pick a point on that graph and drew a line through it. Your ruler told you exactly what the forecast was going to be. That long, slow decline you see, that’s basically my career. Then a funny thing happened called fracking.

It was almost having to change religion. Because the postulate of our religion was oil production will always fall about [inaudible 2%? 10%?] a year. It always does, it always has. That’s where it’s going. When it shot up through the roof, it was sort of like a resurrection. You’ve seen the resurrection, it makes a new believer of you. It took a long time for those of us [inaudible] to accept that this was real. Now we’ve tripled the oil production in the state of Texas. From basically a million barrels a day up to 3 million. It is starting to tail off as you can see now. Because as you know a lot of the wells we drilled today are much shorter-lived wells. You get greater production within the first 5 years, [but] you’ve the got most out of it you’re going to. I call this hockey stick we can live with.

To break that down a little bit by field, I’ve looked at [this]… just in 3 big pieces. We’ve got Permian Basin, we’ve got the Eagle Ford, and then we’ve got the rest of Texas. You can see almost the entire lift we got on that hockey stick was out of Eagle Ford. Going from the first oil well drilled in 2008 to where it now lies… the Permian Basin inside. The Permian Basin has also grown. The rest of Texas doing basically nothing. If we can keep these 2 big fields producing and healthy, than Texas will remain healthy. Now, that was production.

The current graph you’re looking at is permit activity. This tells a much more painful story, because these are the applications that are submitted to the Railroad Commission. They’re not the completion reports, but completions are following the same kind of a trend. In all 3 of the major areas—that is,the Permian, the Eagle Ford, and then everywhere else—these have taken a steep decline. I use the unfortunate term of a face plant at my last presentation. That was the only quote that the press gave me, thank you very much. You know who you are.

This is an unfortunate fact of life. Volatility is part of this business. If you expect to have nice flat line activity like we do in downstream, then you’re not going to last very long in this business.

Let’s look a little bit at what happened to the cost.

It looks like, over 18 years, that the cost of drilling a high-cost gas well has gone up. It was about half a million dollars in 1996 and hit 6 million dollars in 2014. This tremendous run up, it was supported by price, of course, but also the fact that we had limited numbers of manpower and rigs and bid everything up, but I expect that number to come down.

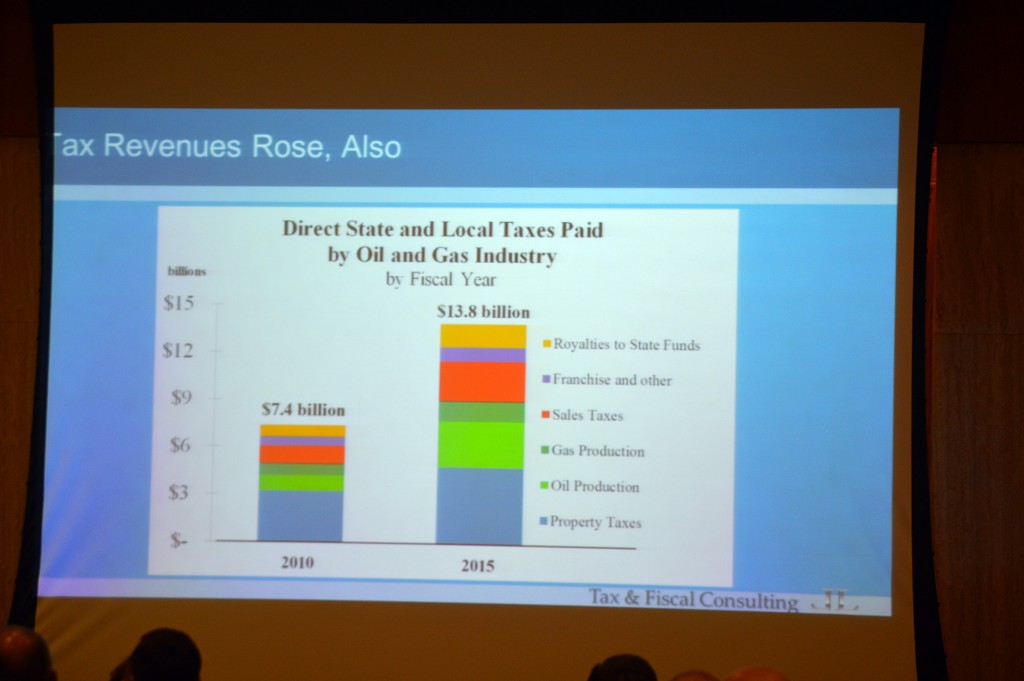

That’s a red line and I want you to keep your eye on the red because in the next graph, you’re going to see where the influence has been felt, in terms of state and local finance. The red bars you see here, that’s sales tax paid by industry. Most of it’s upstream because up to now, almost everything y’all buy is “plus tax.” You buy a drilling rig, you buy a drilling [inaudible], you buy a drill bit. It’s 40,000 dollar diamond tip bit, it’s like putting a Lexus down a hole and grinding it to pieces. It’s “plus tax,” just like buying a pair of shoes or a computer. I think a lot of people don’t realize that, but in 2015, and this is my estimate, but the industry paid over two and a half billion dollars in sales tax.

Problem with it is, you only drill a well once. These other bars you see, royalties, property tax, severance taxes, those go on and on for years, don’t they? Once you’ve got a well in production it’s going to produce taxes of that nature. Sales tax, on the other hand, you drill it one time. Each well typically brings in 100,000 dollars in sales tax, and I’m afraid that’s where it’s going to shrink dramatically when we get the data for 2016.

Even so, 13.8 billion dollars. That’s still some bragging room, given that we have virtually doubled where we were in 2010. Even in a pretty bad year, oil and gas remains a substantial contributor to state and local finance. Royalties to state funds, that’s a permanent school fund, permanent university fund. The oil and gas production taxes go to the state, property taxes go to your school districts, cities, and counties. If it’s something to where it’s sort of a red badge of honor, your tax burden is that.

This graph here I poached from Karr Ingham. Y’all may know Karr, he’s just from down the road. Puts together what’s called the Texas Petro Index, which is a combination—a composite index– of things like employment rate, [rig?] count and oil and gas prices, and it tells a very dark story. This is a data point only through December 2015, but you can see we went from an all-time high in November of 2014 to just 13 months later, back to where we were in the best of 2009. Again, I’m afraid that when we get additional data points, it’s going to show things continuing to fall. His index is not just an index of current activity, but it is an unfortunate leading index. As long as that thing’s trending down, it does not look good for us.

Now, a little bit about property tax. Again, I don’t think many people know this, but the dirt under our feet is the basis of property tax. It’s not just people’s homes, but the reserves. If y’all had gone out and drilled for and developed, and they’re now proven, [those reserves] are on the tax rolls. Over the past 15 years, the value of oil and gas mineral properties went up 316%, for school tax purposes. That’s helping to fund all the schools, whether they’re in this area or what we call a “Robin Hood district,” you have to send money away, it helps the entire school finance system. As much as we hear people complain about their property taxes, and I understand that, oil and gas properties have gone up more than double the rate than anyone else in the state. You’ve gone from helping a lot to helping a whole lot. Though it has dropped off last year, you can see we had about a 20% decline in one year, I think it’s going to drop again this year. Oil and gas is going to remain a key part of the local tax base for many years to come.

Now, a little bit about downstream operations. I’m just going to talk about refining because it’s the single biggest employer and biggest part of that, but Texas actually remains primarily a refining state. We are a big producer, we produce about three million barrels a day, but we refine over five million barrels a day. This goes way back. You can see at the beginning of this graph, 2000, we were only producing about a million barrels a day, but already refining four million barrels a day. We are a big refining state.

The capacity continues to rise in Texas, but it comes at the expense of other states, because refining is a zero sum game to the U.S. U.S. demand for refined products is flat, and has been for a long time. If we’re increasing our refining capacity, it’s because somebody else is losing. Over the past 30 years, more than half of the refineries in the U.S. have closed. There used to be over 300. Now there’s, I believe, 147. Texas has 27, and every year or even every six months, another refinery goes (claps) like a soap bubble, disappears somewhere and we end up, if we’re winning, we end up being able to keep that kind of refining capacity, which is important because this things are gigantic economic generators.

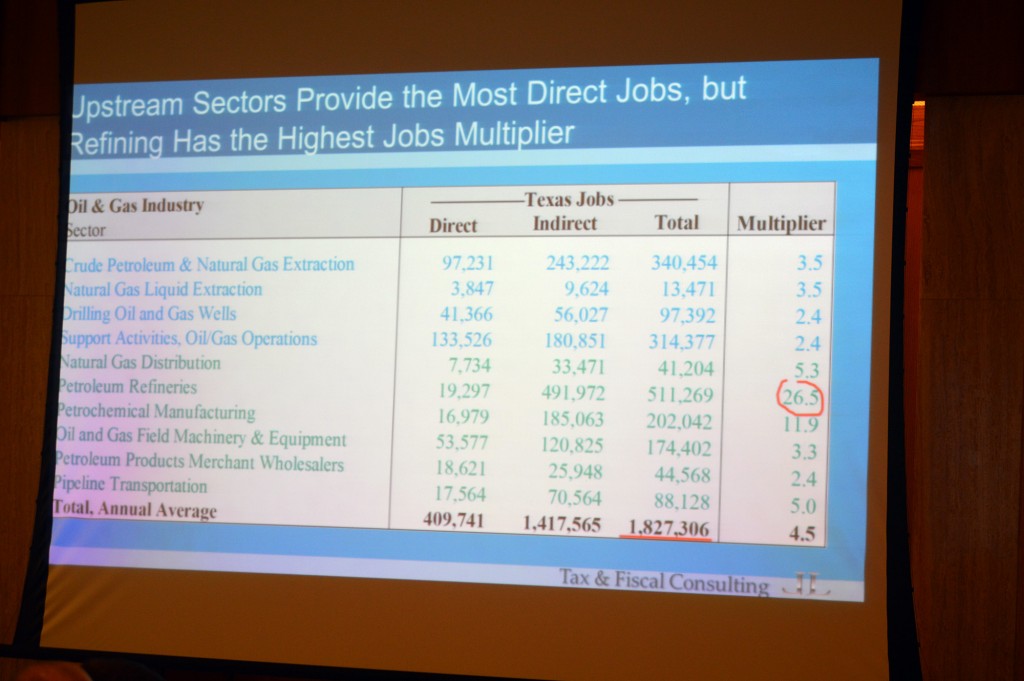

If you look at this slide, and I apologize, it’s kind of an eye chart, but the number that I’ve circled in red, for refining, has a job multiplier of 26. If you’re looking at a refinery, it’s got 400 people working there, that’s not 400 people working there. It’s 10,000 in Texas [who] depend on their job from that refinery staying open. If refineries are closing around the rest of the country, we don’t want any of those to be closed here. Our upstream operations, of course, still have positive multipliers. They’re in the two to three range, instead of 26, but on average, Big Oil and Gas, what I call it, that’s all oil and gas sectors together, support 1.8 million jobs in Texas. 1.8 million, and that includes the indirect effects, and an average job multiplier of 4.5, so we’ve got 400,000 plus, and then a multiplier of 4.5 gives you 11.8 million. We’ve got to have oil and gas for Texas to be prosperous.

We’ve got kids in school, we’ve got kids going to college, people driving on the roads, people going to hospitals, people going to parks, people going to jail. Our population is our big driver on what it costs the state budget. And given that we have a business tax heavy system, and we have no personal income tax in Texas, we don’t want one, but we rely on business to pay 63% of our taxes. So if we are going to have a business-based tax system, shouldn’t we cover the number of people? That’s really what this [inaudible] is: per job, per person. Oil and gas last year paid $34,000 dollars in taxes per job. That’s more than some sectors paid in wages. The average for the other private sectors; $4,600.

Everyone feel free to print this out and show it to your legislator. Now if we don’t have oil and gas, what happens? We reduce our general revenue. The state is heavily dependent on severance taxes and sales taxes paid by business… By this business. The highway fund is now getting a break off of the severance taxes, so we get fewer roads. The rainy day fund… Does anybody know where that money came from? It came from you, thank you very much. The only contribution to the state’s rainy day fund is what we call excess oil and gas taxes. Three-fourths of any excess over the 1987 [inaudible] gets split between the highway fund and the rainy day fund. We’ve got 9.6 billion dollars in the rainy day fund, and it’s all for you. We also funded what’s called the SWIFT, the state water infrastructure Texas fund? The SWIFT fund. Guess where it’s funded from? The oil and gas severance taxes. The permanent school … Permanent university fund? One hundred percent of the net new capital that flows into those funds is from oil and gas royalties. We’ve got to have a healthy oil and gas factory if we want to have a healthy Texas.

That concludes my slides, but I want to allow, if there’s any time, for Q & A to take any questions or comments … Anything that you want me to bring back up. Members of the press? Where’s my Dos Equis? Oh, yes sir?

Yes sir. The question is “What has happened with the property tax front with the decline in oil?” We’ve got about a 20% decline in oil last year, and based on what the Department of Energy Information Administration has put out, it looks like another 20% is going to fall this year. Now that doesn’t mean that your tax falls, because local taxing jurisdictions are able to offset that with a tax rate increase. Now, a lot of them have been dropping their rates as this phenomenon has unfolded, they’ve been lowering their tax rates, and that’s appropriate. Probably not lowering them as much as the values have been going up, but now that the values have been falling, they will probably be increasing. So your taxes won’t be falling at 20%, but they fall some. Yes sir. In the back?

That’s a good question. The question is about … There is a court case, and oral arguments were just heard this week or last on the state’s authority to put sales tax on down-hole expenditures like case and tubing … Cement. Since 1961 that has all been taxable, under the sales tax, but that has been challenged by Southwest Royalties, and the state has put an estimated cost, if they lose, at 4 billion dollars. That would be the refunds that they would have to pay if the Southwest Royalties prevails. And then it would be an annual reduction as well that would hit the state revenue and probably be built into the next state controllers revenue estimate or drive the next budget.

Four billion dollars is basically the entire state’s surplus that is estimated for this bi-annual. So if by some chance industry wins this case, and [inaudible] entered an Amicus brief in favor of Southwest Royalties, so we are for the case, but it would wipe out the state’s surplus. I don’t know what the odds are of victory in this case. The state has prevailed both at the trial level, and the appellate level, so the Supreme Court would have to overturn those things, but the fact that they took the case, is normally a sign that they want to overturn. They don’t normally take cases to affirm the lower cases. About 90 percent of the cases the Supreme Court takes are in the purpose of overturning the lower court. So 4 billion dollars is the official estimate. I have been involved, and the state has lost big cases, and they pay, but they drag their feet as long as they can.

[Another question]

Oh, you want to know the price of oil this time next year? [Laughter.] When it comes to oil price forecasting, there are two kinds of people. There are those who don’t know … No there’s just one kind. I used to do the state’s oil and gas forecast, and we got lucky a few times, and so people thought I knew something. No. I think we are at the bottom, I will say that. The question was “Is this 1986, or is this 2009?” You know, in 1986 we were down in the dump for 14 years, and in 2009 it was about 14 months. Let’s just pray this is another old time. But I don’t know. But I probably wouldn’t be standing here at this podium [if I did] [Laughter.]