When all other hope was gone, “Call Kinley” was the call that went out. Myron Kinley, the man who taught Red Adair how to fight fires, was an oil well firefighter of considerable repute himself.

by Bobby Weaver

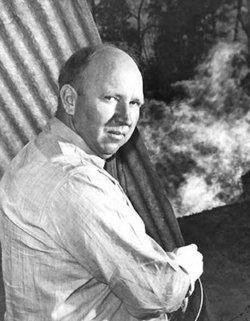

On May 12, 1978, at Chickasha, Okla., a soft-spoken huskily built man of medium height passed away from natural causes. At the time of his death, he was almost totally deaf, his back was solidly scarred by burn tissue, and his right side was partially paralyzed, causing him to walk with a decided limp. He earned all those injuries in the course of more than a half-century working at one of the most dangerous occupations on earth. The man by the name of Myron Macy Kinley, who in the course of developing most of the techniques used in modern oil well fire-fighting, trained such legendary firefighters as “Red” Adair, “Boots” Hansen, and “Coots” Matthews.

Myron Kinley was born at Santa Barbara, Calif., on Nov. 2, 1898. When he was only a toddler, his father moved the family to Bakersfield, where the elder Kinley found work as a well-shooter in the Taft oilfield. In September of 1909, Myron’s mother died and Mr. Kinley was forced to place his children in a foster home. Myron did not adapt well to that environment, and in 1912, at the tender age of 13, he ran away to join his father. He was big for his years, lied about his age, and soon found work in the oilfields of California.

A year later, young Myron was on the scene when his father helped Ford Alexander extinguish the first California well fire with the new and untried method of using explosives. Myron’s oilfield career was interrupted by a stretch in the Army during WWI, but early in1920, less than six months after leaving the service, he was part of the crew that shot out the second California well fire by use of the explosives method. In 1921, he and another shooter named John Percival left California for Tulsa, Okla., where a boom was in progress. They formed an ill fated well-shooting company that lasted only a year, after which he went into business with William J. (Billy) Donnell in another well-shooting business. Myron parted company with Donnell in 1923 but he kept the business going and persuaded his younger brother, Floyd, to join him in Oklahoma. In 1926, he incorporated the company under the name the M.M. Kinley Company.

In the spring of 1924, Myron persuaded an operator in the Cromwell field to let him shoot out a fire within 48 hours or there would be no fee. He and Floyd extinguished the blaze in half that time and they were on their way to becoming the preeminent fire fighters in the Mid-Continent Field. Over the course of the next five years they extinguished fires for virtually all the companies in the region and transformed the use of explosives into an acceptable means of fire fighting.

During that time frame, in association with the Johns-Manville Corporation, Myron designed an asbestos suit for protection while fighting fires. That device, although very useful at times, was seldom used by the brothers, who preferred wearing three or four layers of water soaked work clothing, which gave them more freedom of movement. In 1931, the Kinley brothers were called to the Cole No. 1 fire, near Gladewater, Texas. It was there that Myron received his first major injury. A couple of days after arriving on the scene, a falling I-beam crushed his ankle and he was rushed to the local hospital for treatment. The following day, he was back on the job—hobbling around on crutches helping Floyd shoot the fire.

During the Gladewater episode, Myron designed a device he called “the hook.” It consisted of several pieces of pipe, arranged like a boom, that could be maneuvered into position using a caterpillar tractor. Water was pumped through the pipe to cool the nitro shot suspended on the end of the boom so that the shot could be placed exactly at the spot the shooter needed it without him having to venture into the blaze. Variations on that device have remained one of the primary tools used in oil well fire-fighting to this day.

Shortly after completing the Gladewater job, Kinley began work on the venture that would gain him worldwide fame. That summer of 1931, he traveled to Romania to view the Moreni No. 160 well fire. It had been burning for more than two years and was considered to be impossible to extinguish. When the fire began in the spring of 1929, the company decided that the best approach was to dig a tunnel through the unconsolidated soil of the area and tap the casing at a depth of 200 feet in order to divert the gas flow in a controlled manner. Unfortunately, the tunnel filled with gas and exploded. They tried again with similar results. Then they attempted a much larger tunnel at a greater depth with much the same luck.

By the time Myron arrived on the scene, escaping gas had formed a crater around the well head that was 250 feet across and 65 feet deep, which had swallowed the drilling rig, all associated pipelines, and other assorted equipment. Gas escaping through the loose soil was seeping upward around the crater edges where numerous small blazes were burning. The main gas source, sending flames soaring hundreds of feet into the sky, came from the well head that by then lay 65 feet down at the bottom of the crater. Any excess gas tended to settle back into the crater, which caused continuous dispersed feed for the blaze. At times, the blaze extended as much as 300 feet outward, depending upon the direction the wind was blowing. Some said that the entire scene was like a vision of hell on earth.

Kinley began work on the fire the first week of August, 1931, and completed the job the first week of February 1932. He began by installing a massive vent hood over the well head in order to vent the gas flow in a concentrated manner above the crater so he could shoot it out at the well head. After a couple of unsuccessful nitro shots, the vent collapsed, forcing him to change tactics toward cleaning out the original tunnel where he installed a massive exhaust fan to clear gas from the crater. Ultimately, after several failed episodes—some which temporarily killed the fire—he subdued the blaze, removed all the wreckage from the crater, pumped 25 feet of cement into the cavity, and capped the well.

By the spring of 1932, he had achieved worldwide fame and was even featured in the “Ripley’s Believe It or Not” newspaper column. After the Moreni No. 160 job, work began coming in from locations around the world. Myron handled most of the overseas work while Floyd concentrated on the domestic side of the business. In 1935, he moved to Houston to better manufacture and market his growing number of well-control inventions. The move also made it easier to access the foreign market and the Gulf Coast oilfields. Floyd remained in Tulsa, where he operated the domestic branch of the business.

Early in 1936, the Kinley brothers were summoned to Venezuela to extinguish their first offshore fire. The well lay three miles out in Lake Maracaibo. There was hardly any precedent for fighting oil well fires on water, and it soon became apparent that standard dry-land procedures would not work. Accordingly, Myron had a derrick constructed and towed to within 600 feet of the blazing well. Then they drilled a slant hole that intersected the bore of the wild well several hundred feet below the surface and pumped in heavy mud that overcame the gas pressure and killed the fire. Directional drilling was a relatively rare procedure at that time and its radical use on a burning well marked a distinct new approach to wild well control.

Later that same year, Myron was called to a fire near Bay City, Texas, on a relatively routine job that required clearing away a significant amount of wreckage before actually shooting the fire. While he worked to place the first nitro charge, the charge went off prematurely, shattering Kinley’s right leg and severely injuring his right side. He was hospitalized for six months and bedridden for 18 months. For the rest of his life, he walked with a severe limp and was partially paralyzed on his right side.

During the first week of March 1938, although not fully recovered from his accident, Myron was helping his brother on a fire near Goliad, Texas, when Floyd was killed by falling rig beams. After the explosion injury and Floyd’s death, Myron maintained it was only a matter of time until his disability would cause him harm. That day of reckoning came in 1945, on a job in Venezuela, when an unexpected burst of gas ignited and engulfed him and his crew. Unable to run as fast as the rest of the men, his water-soaked clothing actually caught fire and the resulting steam scalded his entire back. He spent six weeks lying on his stomach in a Venezuelan hospital before he was transferred to Houston, where he spent a long convalescent period. For the rest of his life, his back was covered with a massive area of burn tissue.

That episode marked a period of change in his life. In 1946, he hired his son, Jack, to manage sales, patents, tool development, and marketing for the M.M. Kinley Company. That same year, he also hired Paul “Red” Adair as a fire fighter. Over the next several years, Adair, along with the help of Edward “Coots” Matthews and Asger “Boots” Hansen, assumed a stronger and stronger role in the fire fighting aspect of the business. In 1950, Myron decided to retire to Bel Air, Calif., but that enforced inactivity lasted only a few months. In 1951, he sold the well-control equipment manufacturing aspects of the company to his son, who changed the name to the J.C. Kinley Company while Myron retained control of the fire fighting part of the business, utilizing all his old employees.

He continued this fire fighting activities, fighting fires in such far-flung places as Iran and Japan. On Jan. 17, 1957, his wife of more than 30 years died, and on Nov. 2, 1958, he married Jesse Dearing of Chickasha, Okla., and lived there for the rest of his life. In 1960, after extinguishing a fire in Japan, he announced his retirement from the oil well fire fighting profession, to which he had contributed most, if not all, of the basic techniques. Over the next 18 years, he spent his time attending oil industry conventions of one kind or another and lecturing on wild well control with the exception of one incident in January of 1965, when, at the age of 67, he extinguished one last fire near Canton, Okla., as a favor to a friend.

Red Adair formed his legendary company upon the retirement of Kinley, with Boots and Coots working for him. Years later, they left Red and formed their own company to continue the work that all of them learned from the man who professionalized the most dangerous job in the world.

Bobby Weaver is a regular contributor to Permian Basin Oil and Gas Magazine. His humor column, “Oil Patch Tales,” can be found.