Pressing road concerns wind their way up the priority list.

By Julie Anderson

At least a decade ago, it was coming up in our rearview mirror. We glanced behind us and acknowledged it, and we even began talking about it: the need to fix our roads. Every now and then, it would make the news. Then, we’d face a hill or a mountain (water shortage, education funding, health care, industry decline, etc.), and the road issue would disappear in a valley, eclipsed by other pressing concerns.

Well, it sped up, making deep ruts along the way. It signaled, sometimes tragically so with traffic fatalities. And now it has passed us by, and we have no choice but to launch pursuit—serious pursuit.

Inside the microcosm that is the oil and gas industry, roads serve a determined purpose—to carry our trucks and equipment and final product. Outside our microcosm, roads serve other purposes, including carrying our emergency vehicles, our school busses, our families.

When it comes to roads, there could be an “us versus them” mentality. In fact, headlines noting, “Overweight trucks tear up area roads” may lend themselves to a negative mindset, pitting the big oil company against the community whose roads are left in ruin once the drilling is done. However, when we take a thorough look at the oil industry and its relationship with those using the roads and those maintaining the roads, a different picture emerges. Generally speaking, all parties—users and maintainers on state and local levels—have prioritized the issue and are ready and willing to work together for a win-win.

State Roadways

Dozens of stories have been written regarding the benefit of the oil industry at the statewide level. Even in the midst of the downturn, the fact remains undisputed: oil and gas is a plus when it comes to state coffers, especially over the long haul. In 2013, the State of Texas, via the Texas Legislature and the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT), acknowledged the resulting damage to county roads (see One County’s Story, below) and earmarked money for repair. Earlier this year, TxDOT recognized the need to address state roadways, as well.

In March 2016, TxDOT proposed a program to strengthen pavements and provide safety enhancements on key roadways in energy sector regions.

The downturn in oil prices since mid-2014 has led to a normalization in drilling activity in Texas oil fields. However, while the future pace of drilling is unpredictable, energy sector analysts expect the current slowdown to be temporary. In the meantime, it offers an opportunity for TxDOT to improve certain roads before energy-related traffic returns to previous growth, said Randy Hopmann, TxDOT director of district operations.

The improvements will include:

- Strengthening pavement structure

- Adding shoulders to protect pavement edge

- Adding turn lanes at key intersections

- Constructing passing lanes on Super 2 corridors

On major corridors within energy areas, TxDOT districts have identified and prioritized projects with the greatest need and developed project scopes and estimates.

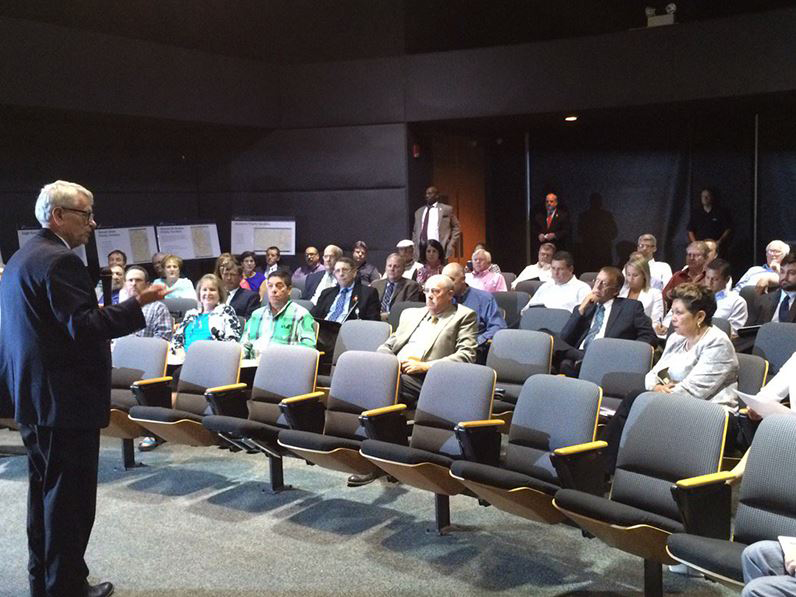

On June 8, Texas Transportation Commission Chairman Tryon Lewis and TxDOT leaders presented details on the new Energy Sector Corridor Improvement Program in Midland to a public audience including political officials and representatives from the areas whose roads have been impacted by oil and gas activity.

Hopmann told participants that TxDOT is seeking $1.8 billion to repair, update, and modify “Priority 1 roads” in Texas’ energy sectors, while another $1.52 million is needed for Priority 2 roads.

Regarding the Permian Basin, specifically, the state agency is seeking $676 million for Priority 1 corridors:

Permian Basin corridor priorities:

- SH 302

- FM 652

- SH 158/US87

- US 67

- SH 176

- US 87

- US 285

- US 385/SH 214

- SH 349/US 87

- SH 137

- SH 350

The program will be funded through TxDOT’s Unified Transportation Program, and the Transportation Commission is scheduled to adopt the program in August, Hopmann said. The money will come primarily from taxes generated by the energy sector—specifically, oil and gas taxes and gas severance taxes.

“This is a $3 billion program, and we expect it to take seven-to-eight years to fully implement it,” Hopmann continued.

When it comes to the role of industry players, Hopmann suggests two modes of action:

- Offer your input during the public comment period for the proposed Unified Transportation Program in August.

- Contact the district engineers in your areas and let them know which specific projects you are interested in and talk about what improvements are needed in these areas.

“Our goal is to develop a working partnership that will help us deliver the right projects at the right time,” Hopmann emphasized.

State roadways are not the only ones taking a pounding. In fact, county roads have taken an even deeper hit. Thankfully, in an unprecedented move two sessions ago, the Texas Legislature signaled it was ready to lend support.

One County’s Story

It’s not every day that county government makes the Wall Street Journal. However, on July 27, 2012, one of the country’s largest newspapers shared with its readership the emerging plight of Texas counties both blessed and challenged by the oil and gas industry. DeWitt County Judge Daryl Fowler was quoted in the article titled, “Drilling Strains Rural Roads: Counties Struggle to Repair Damage From Heavy Trucks in Energy Boom.”

Some three weeks earlier Fowler penned a press release of his own with the following lede: “The Eagle Ford Shale Play in South Texas could be the most significant economic development in Texas history. Lying under at least 24 Texas counties and containing liquid hydrocarbons as well as natural gas, it is bringing new life to many declining towns. It is a mixed blessing, [one] which manifests itself in similar ways all across the Play. DeWitt County is experiencing the rebirth firsthand: an exploding tax base stemming from unprecedented economic activity, and balanced by what was, until now, unquantifiable road damage.”

Months earlier in March 2012, Fowler was appointed to the Task Force on Texas’ Energy Sector Roadway Needs, established by the TxDOT and comprised of representatives from the Department of Public Safety, Department of Motor Vehicles, Railroad Commission of Texas, Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, Texas counties, and the energy and trucking sectors.

Fast forward four years to July 2016, and Judge Fowler still maintains that the industry is a blessing, as evidenced the judge’s summary:

“The resurgence of domestic oil and gas investment activity in the United States, Texas, and certainly in our region, has a tremendous long-term benefit. Population outflows from our rural counties to the metropolitan areas have crippled, if not doomed, many counties. If the next generation cannot find jobs that use their talents and cannot raise their own families where they were raised, then the end result is a loss to the community spirit and economic benefit.

“Oil and gas development has opened doors for the current families to find good or better jobs and add to the tax base and local school populations, which is helping to stem the ebbing tide. Until the Eagle Ford Shale came along, our over-age-65 population was growing, and the tax freezes associated with their homesteads was consuming a large part of the cost-shifting of funding public services to those under age 65 and to businesses. It is altogether different right now. School districts are expanding and modernizing; homes are being built; and some of the college-educated former residents are moving back to high-paying jobs that they felt they could only find in the big cities.

“Additionally, we have made huge strides in reinvigorating our Local Emergency Planning Committee (LEPC) because of the huge industrial component in our economy. The oil companies have been at the head table with this effort, and they have been huge benefactors for our seven rural volunteer fire departments. Our EMC and the LEPC work hand-in-hand to make sure that the front-line responders have the firefighting foam and poison gas sensors. It is a remarkable thing to witness a formerly BBQ-and-raffle-ticket-dependent VFD benefit in this way, and I am comforted by the evidence that these oil companies do care about the communities they work in. The evidence is in.

“Finally, the early internal growing pains were witnessed in the county clerk and district clerk offices. In 2011, there was more than $50,000 received for copying of documents related to land and mineral ownership, and that eventually moved to the other side of the table with the filing of leases and other instruments of record. Along the way ConocoPhillips offered to pay for a major 21st Century improvement in our traditional hard-copy, bound-book record keeping system. They offered to pay for a digitizing campaign, and we took them up on it. More than 700,000 pages were scanned. Title companies, oil companies, and other users now access these records through hard drives, and the burden in the county clerk office has decreased. The income is much lower, but overall the $400,000 gift was worth it.”

With all that said, Judge Fowler has no choice but to address the challenges of the industry: the damage done to county roads.

“Road degradation will always be a challenge where oil and gas is produced,” Fowler declared. “We can rebuild a road to the design the engineers say we need, and as soon as the first rig move occurs, we see it being consumed all over again. Our standards are high, because we want the roads to last a long time. Therefore the costs seem almost prohibitive at $350,000-$400,000 per mile.”

Early on, two drilling companies, Petrohawk Energy (now BHP Billiton) and Pioneer Natural Resources contributed $8,000 per well bore in DeWitt County on a voluntary basis, Fowler reported. These companies signed voluntary road use agreements with the county in 2010 and 2011, which renewed annually. Unless there were extenuating circumstances or limitations in the agreement, the $8,000 donation was used for road maintenance, Fowler confirmed. The county divided the receipts among the precincts where the new wells were located. The voluntary contracts expired under their own terms at the end of 2012. The cumulative, combined donation to the county road effort was a little over $2.6 million in the two-year period.

“The contracts worked out to be a great ‘bridge financing’ mechanism [with no pun intended]. The donations were timely, in the sense that they arrived monthly, and they were vital until the ad valorum tax base could catch up,” Fowler stated.

DeWitt County hired an engineering firm to assess the drilling campaigns, the traffic flow, the overweight truck permits, and more in order to define what current and future needs were likely to be. The final report summary of the Naismith Engineering study indicated that DeWitt County had a potential $432-million problem to solve if the county wanted to maintain a focus on public safety and accommodate the needs of the oil and gas industry.

“Our rights of way were, and still are, not wide enough to handle the super-structure rig movements, and they were, and still are not, beefed up enough in many places to handle the weight of a rig move,” Fowler detailed.

The judge introduced the Naismith Engineering study to RRC Commissioner David Porter’s Eagle Ford Shale Task Force at a regional meeting held in Cleburne in Summer 2012 and achieved some general support from the oil and gas industry.

“The industry concerns naturally focused on who was going to pay for it all,” Fowler shared. “After all, they were sending billions to the state in severance tax already.”

One benefit of allowing the voluntary donation contracts to expire at the end of their primary term in 2012 was that Fowler “was forced to mount a serious campaign for legislative awareness of the almost insurmountable road deterioration problem and seek solutions that would: 1) provide more opportunities for local revenue (as in finding common ground to modify revenue cap limitations in energy impacted regions), and 2) engage state leaders about state responsibility and the need for state funding,” as described by the judge. The state’s severance tax was yielding billions for the Rainy Day Fund, but local county taxpayers were left paying the bill for damages.”

And mount a campaign he did. Fowler and others across the state struggling with industry-related road damages took to the capitol and shared their plight with facts, figures, and photos in hand. Industry representatives joined the cause as well, supporting a state contribution to the county road system. Their efforts paid off. During the Regular Session of the 83rd Texas Legislature, House Bill 1025 appropriated $225 million for county road repair for damages from oil and gas activity. Senate Bill 1747 created the grant process to distribute funds to counties through the TxDOT.

Former Hays County Commissioner Bill Burnett labeled it a “quantum leap in thinking.” Fowler described it as an “unprecedented move.” And while both admitted it is a mere “drop in the bucket,” the state’s decision to earmark money to a transportation infrastructure fund was certainly a step in the right direction.

The new legislation amended Chapter 256 of the Transportation Code and created a Tax Infrastructure Fund (TIF) for County Energy Transportation Reinvestment Zones (CETRZ).

The TIF is a dedicated fund in the state treasury outside of the state’s general fund, which shall administer a grant program for transportation projects if the TIF has a positive balance, Fowler explained. Grant money from this fund was dedicated to projects defined by the statute as “the planning for, construction of, reconstruction of, or maintenance of transportation infrastructure, including roads, bridges, and culverts, intended to alleviate degradation caused by the exploration, development, or production of oil or gas.”

After calculating eligibility using a statutory formula, TxDOT allocated funds to all 191 counties that submitted applications. The approval of the grants was delayed while TxDOT developed grant rules and documentation. As of press time, 175 counties had submitted invoices requesting reimbursement of $125 million. The current appropriation and projects have been extended until Aug. 31, 2017, and officials are hopeful that more will be allocated during the next legislative session.

DeWitt County was allocated $4,957,613 for four projects which eventually cost the county close to $8 million.

“A reminder here is that the supplemental appropriation of $224.5 million for the TIF Grant program [statewide] was less than the $244 million in severance taxes that the state received from the oil and gas severance tax collected from oil and gas companies and royalty owners on DeWitt County production in 2013,” Fowler stated.

Julie Anderson, based in Odessa, is editor of County Progress Magazine, and is well know to many readers of PBOG as the former editor of this magazine.