Every problem holds the seeds of its own solution. How the crude oil price collapse—grasped holistically—reveals the steps that will right the ship. First glimmers of a better day coming.

by Jesse Mullins

It was Will Rogers who said that an economist’s guess is liable to be as good as anyone else’s.

When the question comes to what the short and long term future holds for oil and gas in the Permian Basin, the guesses are plentiful. It’s been almost two years, now, since the price of crude oil suffered its steep decline after members of OPEC were unable to come to agreement on production curbs at a meeting in Vienna. Dropping from more than $100 a barrel to (at times) less than 30 percent of that amount, the decline has been devastating. And it has spawned a cottage industry of clairvoyants who have showered upon us an unending profusion of prognostications and pontifications on the character, the causes, the culpability, and the (hoped for) correction of the current malaise.

One thing that’s likely been frustrating, for the oil patch, about the abundance of opinion has been the way that it so quickly became the preroggative of Wall Street and of media types heretofore unversed in the ways of the oil industry—opinion givers who suddenly had answers to the whole debacle.

And so, while we’ll cite a number of views by various economists and industry observers in this multi-part series, some of them hitting closer to the truth (OUR opinion, anyway, and it is liable to be as good as anyone else’s), and some hitting farther afield, we hope to ground this conversation in the thought of an economist who at least has made a career of studying oil and gas, and not just any oil and gas but mainly Permian Basin oil and gas. Karr Ingham is no late-comer to our world. He has earned a reputation for accuracy within our own tribe. And so each installment will conclude with some of Ingham’s insights.

And while it was Will Rogers’ brand of wryness to treat economics as “guesses,” and while it might be true that the “guesses” have been more than sufficient, still, it remains that one thing is not a guess. Some form of rebound is inevitable. It’s a cyclical world we live in, and “down” can’t stay down forever.

That seems to be the consensus, no matter who is doing the talking. The differences mostly lie in how the rebound is portrayed. With some observers, it hardly seems like a rebound at all—it’s just some slight, steady improvement in the “lower for longer” outlook. With others, the unwinding of this chapter in oil’s history is more pronounced.

For an example of the former, let’s consider the message conveyed in a recent video broadcast on CNBC, wherein John LaForge, Wells Fargo Co-Head of Real Assets, discussed the “Next Stop for Oil.” Forge, it ought be said, has admitted to believing in the concept of “the self-defeating rally,” which is the idea that, as oil prices increase, that improvement prompts oil companies to bring rigs back on, and that step, in turn, lowers prices, because increasing supply means decreasing demand, and decreasing demand equals lower prices.

“I’m a big believer in these commodities running in long supercycles,” LaForge said. He added, “Where do I think we end up? I think we’re looking at between $35 and $55, probably over the next decade. We’re just gonna bounce up and down as we work off that excess supply of the last bull market.”

Over the next decade, he said. But before you decide that a $55 ceiling is in place for such an extended time, consider the views of another observer, that being John Hofmeister, former president of Shell Oil Company.

Hofmeister, who appeared on the video podcast of the [T. Boone] Pickens Plan (pickensplan.com) in early July, said he believes world oil prices will be $80 per barrel by the end of 2016 and will be at or near $100 per barrel by the end of 2017. He remarked that he thinks India, China, and the African continent all need to use oil to grow their economies.

Meanwhile, Russia, Saudi Arabia, and other OPEC countries are “going broke” by over-producing to try to force the United States out of its leadership position, Hofmeister said. “People say it only costs $5 per barrel for the Saudis to produce,” he added. “But that doesn’t include all of the costs of supporting its people, including the people it needs to import to actually do the work.”

As for our own interests, Hofmeister suggested that we need for politicians to stop thinking like politicians. “A political timeline is two years—until the next election. A typical energy timeline is 30 years,” he said. “Politicians have to recognize the need for long-term thinking as regards energy.”

One phenomenon that would seem to support Hofmeister’s view of $80 or $100 oil arises from the sheer severity of the downturn itself. Pendulum swings tend to have some reciprocity to them: a hard swing in one direction needs to be followed by a hard swing in the opposite direction. Anyone who has been around playground equipment has observed this. In one of the more interesting analyses we’ve seen, The Motley Fool stated, six months ago, that prolonged depression of crude oil prices means all-the-more pronounced upside once the upswing gets under way.

As Motley Fool reported:

“While this year’s global supply shortfall is projected to be relatively minor at 300,000 barrels per day, and easily covered by the glut of oil already on the market, it’s literally all downhill from there. According to Rystad, by 2017 declines will outstrip new supply by 1.2 million barrels with an even wider shortfall projected in 2018 before significantly worsening by 2020 given current projections.’That’s all coming as oil demand is expected to march higher by about one million barrels a day per year because of global economic growth.”

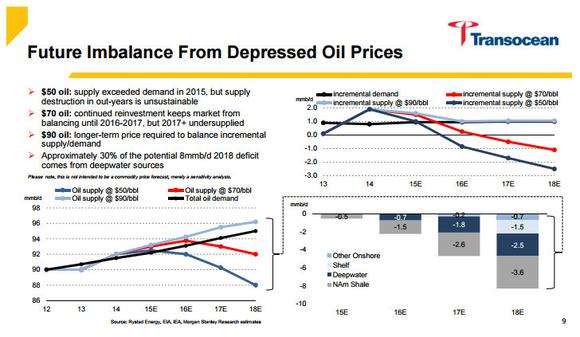

Motley Fool further underscored its point by referencing a chart prepared by offshore driller Transocean (see accompanying graphic).

On the graphic, Transocean takes an amalgam of estimates from Rystad and others, which is then run through three different oil price sensitives. The result is a potential significant shortfall in oil supplies should prices remain under $50 a barrel for the next three years.

As Motley Fool observed:

“One reason for this potential huge shortfall in supply is the high cost and long lead-time it takes for offshore projects to be developed. [To use offshore as an example], a major offshore project sanctioned today might not start producing until 2019. However, given where oil prices are right now, analysts expect only nine of the 232 pending projects to be given the green light this year because most of these projects aren’t economic. That lack of projects moving forward is causing Transocean to caution that its business might not see a pickup in the dayrates of offshore drilling rigs until the 2019 or 2020 timeframe because it will take the industry that long to get back up to speed.”

The author of the report remarked that this scenario can leave a big production gap to fill in the medium term, which actually bodes really well for shale producers, because shale producers’ production cycle is much shorter, often delivering production in months as opposed to years.

“Having said that, given the significant balance sheet deterioration during the downturn, oil prices would need to be significantly higher in order to entice shale producers to ramp up activity,” the article stated. “That just might happen because higher oil prices would be the result of a significant shortfall in supply. It’s a situation that’s only expected to get worse over the next few years unless oil prices vastly improve, which would enable shorter cycle shale wells to fill in the gap until the industry can bring larger offshore developments online.”

Conclusion? “It’s an outlook that suggest that there could be just as much volatility to the upside over the next few years as the sector has seen to the downside in recent years.”

All of which brings us to Karr Ingham, whose analysis takes in ground some others have ignored. One of the differences seen in Ingham’s views, as opposed to those who are less acquainted with the oilfield, is that Ingham understands that supply of oil is not something that is manufactured fresh each year—it has a residual, carryover aspect that many don’t grasp. In fact, in any given year, most supply of oil is not met by that year’s drilling efforts. It’s met by the flow of oil that has been established over preceding years, and the new drilling merely adds a relatively small, supplemental addition to that supply.

In other industries, a fast, steep drop-off in supply can indeed quickly follow a drop in demand. If someone sells paisley shirts, and if the demand for paisley shirts goes down overnight, the factories making paisley shirts can discontinue those lines immediately, and the supply can fall off almost as quickly as did the demand. That’s not true in the oilfield, where most of the flow of product comes from previous years’ work—production that flows this year and will flow next year as well. That production—that supply—is the part of the iceberg that is under water and is not noticed—at least not noticed by some. But it is part of the real picture, and that supply is not affected by anything that OPEC or anyone else does. It just goes on of its own accord. So all (or almost all) that is really hindered by an OPEC-type event is drilling, and drilling activity in any given year adds to the overall supply by just a small fraction of that supply. Conversely, curtailment in drilling in any given year only takes away from the year’s supply by just a small fraction of that supply. So change to supply in crude oil happens slowly, whether it goes up or goes down. It’s not like making shirts.

Ingham is clear on that point.

“Those who don’t kind of pay attention to how this process actually works have made a number of common mistakes throughout this series of events,” Ingham said. “Mistake number one is to always assume that the actual amount of production, just the sheer volume of crude oil production, is tied pretty closely, at least in terms of time frame, to other measures of activity. In other words, early in this process, when price first began to decline—and in mid-2014 the rig count held up at least through the end of November, started to fall in December of that year, and then it was clearly falling on a sustained basis in early 2015, along with drilling permits and other such things—well, people who write about this stuff should have known better. But many of those people thought that production decline was going to occur VERY SHORTLY on the heels of rig count decline. That never really ever works that way, whether on the way down or on the way up. These are long lag-time responses. And as a matter of fact, as we went through 2015, production itself probably actually PEAKED in March or April, but it didn’t fall off very quickly, and both in the Permian, in statewide Texas, and in the United States, we produced vastly more crude oil in 2015 than we did in 2014.”

This was true in spite of the fact that E&P companies had sharply curtailed drilling during the same year (2015), even EARLY in the same year.

Ingham continued:

“Finally, 2016 is going to be the year where we produce less crude oil on a year-over-year basis at all of those geographic levels [regionally, statewide, nationwide, and globally] than we did the year before. That will be the first time that that will have happened in some time. My goodness, what would it take to turn that scenario around [to reverse it and turn it upwards] in 2017? Is there any possibility that we’re going to have a year-over-year INCREASE in crude oil production in 2017? There’s no chance that’s going to happen, regardless of what price does between now and then, because of the typical lag-times there.

“What we’re doing now is decreasing production CAPACITY for a considerable period of time on into the future. I happen to think that is the proper market outcome. That’s exactly what the market has been signaling to us, to producers, to the producing community, with low prices. This means, of course, that if we have a strong surge in demand, let’s say in the latter half of 2017, and that demand curve begins to move upward at a faster pace than it is now at the same time the supply curve continues to decline, [then] that’s just a recipe for a rapid price rebound and potential volatility. Does that mean we’re going to go from wherever we happen to be then to $120 in a six-month period of time? We just don’t have any way of knowing that yet. Conceptually speaking, again, I think there’s a solid possibility that that very thing occurs at some point in the future just because of the nature of production decline and how—not necessarily that there’s difficulty—but it takes them TIME to turn that production curve and move it back the other direction, just as it did on the way down.

But Ingham said there were caveats to this scenario. Two, to be specific.

“We haven’t had a great lot of help on the demand side of the equation throughout this contraction so far, and if global demand remains sluggish, if the U.S. economy remains sluggish, kind of locked into this pathetic 1 percent rate of growth that we seem to be experiencing quarter in and quarter out when we see these GDP numbers [then the recovery can be slowed]. Europe remains sluggish, China too, and I’m not sure what we’re looking at there in the coming years. A recession in China is a 6 percent rate of growth rather than a 12 percent rate of growth, but that really cuts into the growth in energy demand. There’s a likely scenario out there, at least a conceivable scenario out there, where China returns to a stronger rate of growth and developmental economies, which is what that one [China] is—we, meanwhile, are a mature, developed economy here—but when they recover from this malaise they’ve been in, again that just points to the possibility that [a very strong price surge] could be out there. Caveat number one is demand. If the rate of demand growth doesn’t pick up, that lessens the possibility that that will happen.

“The other caveat that occurs to me is that it just seems like the industry, even in the last ten years or so, with these technological developments and the rate at which they have advanced, well, it just looks to me like the industry has become more responsive to price changes and price increases, in particular when it come to ramping up activity levels. The other mistake we all tend to make is to think that the industry is a little bit static, that it looks now like it did 15 or 20 years ago. It looks nothing at all like that. We’re not producing from the same rock, we’re not producing with the same technologies. I think, again, the industry has become more responsive to price increases. That may produce an ability on the part of the industry to respond to demand increases faster than they typically have in the past, which again would sort of serve as a damper to the phenomenon that we are talking about.”

PBOG asked Ingham if he was in agreement with so much of what one sees about the Permian Basin these days: that this region is best poised, of all U.S. shale plays, to capitalize on a rebound in crude oil prices. The short answer: yes. But he has his own take on things.

Said Ingham: “The conventional wisdom—and it’s not very hard to find these articles out there… all you’ve got to do is pull up any old webpage that has any news at all on it and somebody talking about oil, and you’ll read that the Permian is kind of the shining star of not just the entire state, but also of the United States and even North America—but the conventional wisdom is a little bit maddening to read, because they suggest that the Permian wasn’t hit nearly as hard as some other areas. But whereas the Eagle Ford lost 80 percent of its rigs, the Permian lost 76 percent of its rigs. When you lose three-fourths of your working rigs, you got clobbered. The Permian really got hit just as hard as anybody else. Is it adding rigs back faster than other producing regions in the country?

“The answer to that question is yes, but it’s not all that difficult to see why that’s the case and why it makes the answer to your question yes. It is better positioned to respond to a price recovery, just because it’s so vast and so complex in terms of its geology that it just has something that other producing areas, like the Eagle Ford, like the Bakken, don’t have, and that is regions of production where the cost of drilling and bringing wells online is less expensive than it is in some other regions. If that weren’t the case, we wouldn’t be seeing an increase in the rig count at $40 oil or $45 oil, but clearly that is the case. [But] that means that if we stay at $40 or $45, then we stay in just the [most profitable areas of the Permian] and we don’t begin to move into these other areas that were so active during the period of time when price was $100.

Watch for next month’s issue when we continue this series with “Anatomy of a Turnaround.”