Santa Rita #1 was the discovery well that opened what would prove to be the biggest oilfield in America, and what might someday become the biggest in the world. Its story is one that epitomizes what the oilfield is all about.

by Bobby Weaver

It has been almost one hundred years since the Santa Rita #1 blew in to set off a series of major oil and gas finds that ultimately resulted in the development of Permian Basin. That notable event took place on May 28, 1923, and the narrative of how it came about says much about the nature of the oil and gas industry. In many ways its story is the epitome of the boldness, tenacity, ingenuity, and just plain old “luck of the draw” that has come down as the hallmark of those working in the industry today.

Like all good oil patch yarns it begins with leasing. Land acquisition began on January 9, 1919, when Rupert P. Ricker made preliminary application for leasing rights on 431,360 acres of land known generally as university land that had been set aside by the state of Texas for the financing of the University of Texas and later Texas A&M University. The land was in Reagan, Upton, Irion, and Crockett Counties. With only 30 days to pay the filing fee of $43,136, Ricker hied himself off to Ft. Worth to raise the money. Nobody seemed to have any interest in the deal so with the deadline looming he sold the entire scheme to El Pasoans Frank T. Pickrell and Haymon Krupp for the sum of $2,500.

The new potential lease owners, with little time left to retain the leasing rights, borrowed the money for the filing fee. They quickly abandoned Ricker’s original plans and formed the Texon Oil and Land Company and began to sell stock in the company. That did not go fast enough as they needed to raise enough cash to show drilling progress before January 9, 1921, or lose their state lease. So they went to plan B by setting aside 16 sections of the land which they named Block #1 in which they sold “certificates of interest” that provided a .0004882 interest in Block #1 for a mere $200.00 per certificate. Despite the fact that the property was more than 100 miles from the nearest oil production, over the course of the next year or so they raised $100,000.

As the deadline neared, Pickrell, who had hired a geologist to find a likely drilling location, used part of the money to buy a quantity of used cable tool drilling equipment and had it sent to a location on the railroad about 12 or 14 miles west of Big Lake near a railroad siding called Best. With time of the essence and travel to the remote location chosen by the geologist difficult, Pickrell decided to ignore his advice (most in the business in those days didn’t trust geologists anyway) and drill closer to the railroad. That location was 174 feet north of the Kansas City, Mexico, and Orient Railway, where he had unloaded the equipment. About midday on January 8, 1921, a crew hired by Pickrell set up a portable drilling unit at the site to drill a water well designed to service the planned drilling operation and by sundown it was operational. Sometime after dark Pickrell spied a vehicle’s lights moving in the distance. He flagged the car down and persuaded the two cowboys in it to sign affidavits swearing that work had begun on the well prior to midnight on January 8, which meant that he had met the deadline and once again saved the lease.

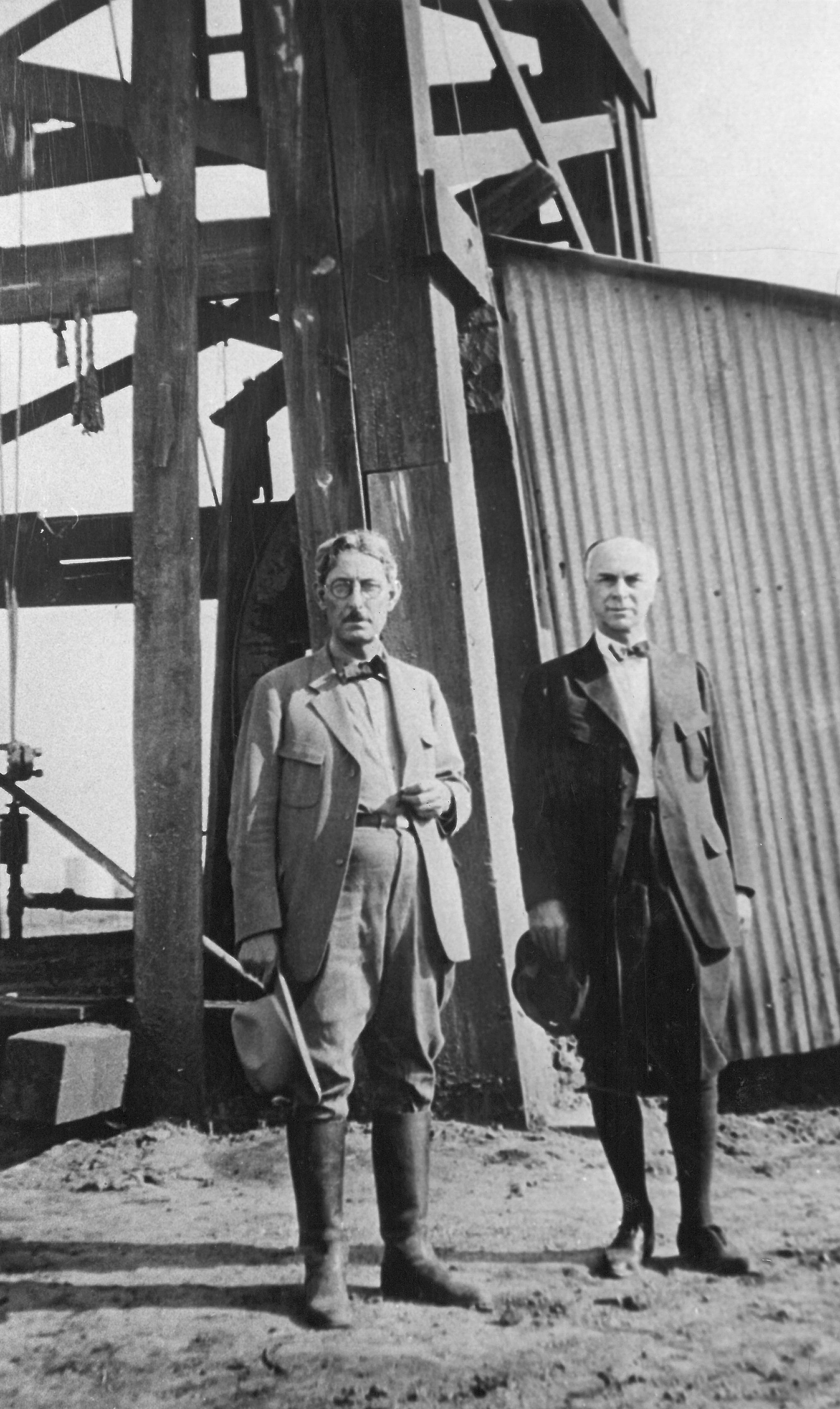

In June of that year a rig building crew was hired to camp out on the site and build the derrick as well as two boxcar-type shotgun houses for living quarters. By the time the derrick was completed Pickrell had hired an experienced cable tool driller named Carl Cromwell for the princely wage of $15.00 per day plus stock in the enterprise. The driller moved his wife and small daughter into one of the houses, used the other as living quarters for local help when he could find it, and over the course of the summer in that isolated and lonely spot managed to gather up the various pieces of drilling equipment that been randomly scattered around the location. It was August before he had a drilling rig assembled and ready to go.

The well spudded in on August 17, 1921. Just prior to that event, Pickrell, in one of the most unusual dedication ceremonies in the history of the oil patch, climbed the derrick, where he threw a handful of dried rose petals into the air and dubbed the well the Santa Rita. That event was precipitated by an unusual request, as he recalled in a 1969 interview:

“The name Santa Rita originated in New York. Some of the stock salesmen had engaged a group of Catholic women to invest in the Group 1 stock. These women were a little worried about the wisdom of their investment and consulted with a priest. He apparently was also somewhat skeptical and suggested to the women that they invoke the help of Santa Rita who was the Patron Saint of the Impossible! As I was leaving New York on one of my trips to the field two of these women handed me a sealed envelope and told me that the envelope contained a red rose that had been blessed by the priest in the name of the saint. The women asked me to take the rose back to Texon with me and climb to the top of the derrick and scatter the rose petals, which I did.”

Cromwell continued to drill on the well pretty much by himself, with the sporadic help of itinerant cowboys or anybody else he could cajole to work. It was not until January of 1922, when an experienced cable tool man named Dee Locklin, who was returning from another wildcat drilling job in Loving County, happened to spot the rig running out there in the back end of nowhere. Cromwell hired him on the spot and Locklin brought his wife out to the location where he worked as tool dresser and lived in the spare shotgun house until they completed the well 18 months later.

That drilling job was a classic “poor boy” operation. During the course of its drilling, progress amounted to less than five feet per day. They were plagued with almost every problem you could imagine, ranging from a variety of fishing jobs to a lack of proper tools or sometimes no tools at all. Help was so scarce that they were never able to keep the rig running on a 24-hour basis. The truth of the matter was that the rig was down almost as much as it was up and running. To top that off, Locklin remembered going as long as three or four months between pay checks.

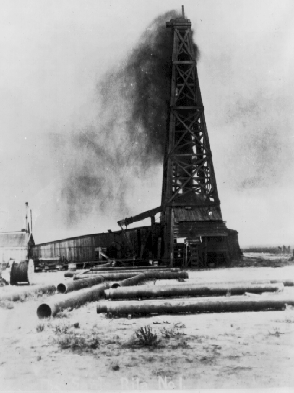

Finally on the afternoon of May 27, 1923, at a depth of 3,050 feet, the two man crew got a showing of oil and gas, prompting them to shut the operation down for the day. The next morning around seven o’clock, as the driller and his “toolie” were having breakfast in their respective houses, they heard a roaring sound. The rose petals, it seemed, had done their job. Upon rushing outside they witnessed oil pulsing from the wellhead. It would ebb and flow several times until it eventually blew over the top of the derrick. Then it would drop to just a trickle and start all over again. That 12- to 14-hour process repeated itself for two weeks before the flow was brought under control. In the interim, oil filled both of the 250-barrel tanks on the location and flooded the surrounding countryside. It has been estimated that the Santa Rita #1 flowed between 30 and 100 barrels of oil per day. It was not the biggest well ever drilled, but it proved that there was petroleum wealth out in those trackless wilds of West Texas.

On the afternoon of the 27th, when they got their first showing of oil, Cromwell and Locklin, reflecting the entrepreneurial spirit of that era, devised a plan. They knew they had a showing of oil so they decided to cash in on the situation. In a 1970 interview Dee Locklin stated that:

We closed down and nailed the rig up, nailed the door down, set the bailer in the hole, and we were not going to work the next day, we were going to buy up some leases around the country, which we did. We did that because we knew we had oil; we didn’t know how much, but we actually knew that much before the well actually began to blow. Then the well blew in. There wasn’t anything we could do about it. We just had to go on. We got 20 or 30 sections leased, I can’t remember for sure. We got it all in one day. It was quite a bit of country to cover, but we made all the ranches and made the deal right there: then we went over to the courthouse, which was at Stiles at that time, and had the papers drawn up.

Although they worked fast before word got out about the successful well, the driller and the tool dresser never developed any production off the leases they acquired that day—although they did make a tidy profit on the deal by reselling the leases shortly afterward.

Meanwhile, Pickrell began trying to realize his own profit off the discovery. Although he and Krupp had a viable well they did not have enough capital to develop the acreage under their control. He began searching for a partner with the necessary backing and it was not until October that independent oilman Mike Benedum, a flamboyant wildcatter from Pennsylvania, became involved. He formed the Big Lake Oil Company and began to develop the field. After that the major oil companies joined the fray and within a couple of years the region became a major operation.

The first royalty payment to the University of Texas in the amount of $516.63 was paid in August of 1923. Since then oil and gas royalties from state university lands have helped make both the University of Texas and Texas A&M University the best funded educational institutions in Texas. In 1940 the original equipment from the Santa Rita #1was salvaged when the Marathon Oil Company replaced it with an all-steel pulling derrick and associated equipment. That original equipment was preserved through the efforts of the Texas State Historical Association and in the 1950s it was installed on the UT campus in recognition of its importance to education in the state. The Santa Rita #1 was taken out of service and plugged in 1990 after 67 years of service.

Bobby Weaver is a regular contributor to Permian Basin Oil and Gas magazine, and his humor column, “Oil Patch Tales,” appears in every issue of the print edition.