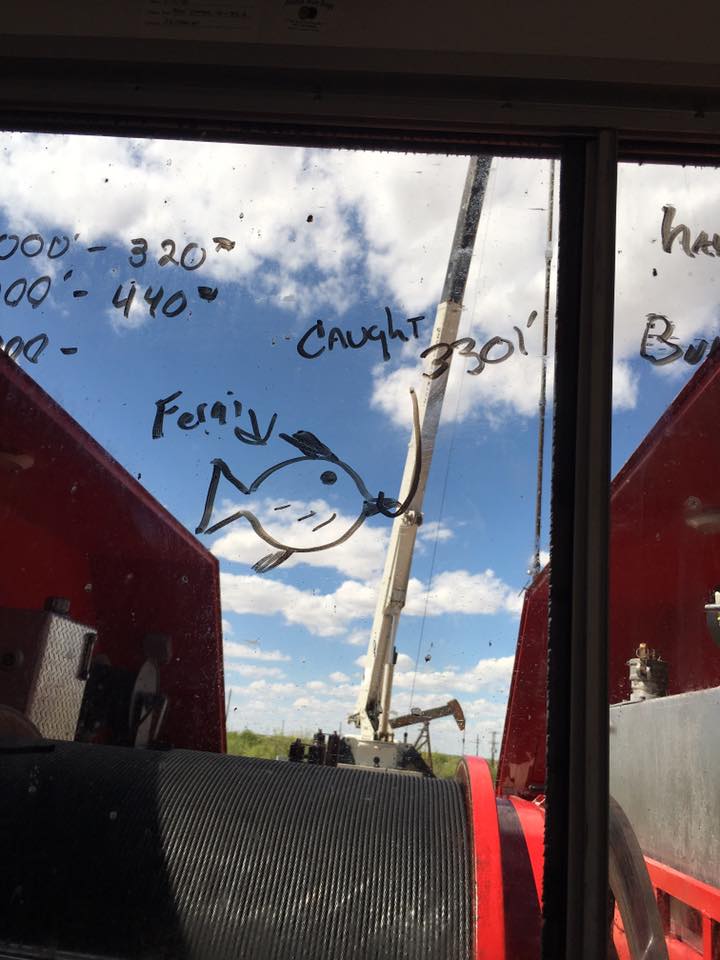

Here’s how Schlumberger’s Glossary defines a “fish”: Anything left in a wellbore. It does not matter whether the fish consists of junk metal, a hand tool, a length of drill pipe or drill collars, or an expensive MWD and directional drilling package. Once the component is lost, it is properly referred to as simply “the fish.” So much for definitions. What follows is the rest of the fish story.

by Bobby Weaver

Oil patch fishermen are a special breed. The fish they seek live deep down in the earth and require specially designed gear to coax them to the surface. The fish oil patch fishermen seek are not live creatures at all, although some might disagree because of their uncanny ability to evade capture. No, oilfield fish are items lost downhole in oil wells and the fishermen are those specialists who remove them from their environment.

Beginning with the 150- to 500-foot oil wells of the 1850s and continuing to those technologically sophisticated 20,000 foot projects of today, one of the most consistent oil well drilling problems has remained how to retrieve unwanted items lost down the well bore. Whoever first called those lost items “fish” or called those who retrieved them “fishermen” has been lost to history. But regardless of how those terms originated, it is acknowledged by oil men everywhere that the unique skills needed for fishing are earned through long experience by persons with the rare ability to visualize what is happening thousands of feet below the surface. That combination of experience and skill is necessary because every fishing job is different, often requiring specially fabricated tools ofttimes created on the spot and possibly used only once.

In the very earliest days of the industry the drilling was done exclusively with cable tool rigs. It is known that they suffered numerous fishing problems but there are very few descriptions of the tools they used. It was not until 1884, with the publication of the Oilwell Supply Catalog of that year, that the first known illustrations of fishing tools came to light. Those listed in that catalog were considered standard devices used for common problems encountered in the retrieving items lost in the hole. There is little doubt that those standard tools were the result of thousands of predecessors created in local machine and blacksmith shops throughout the oil patch during the preceding decades and abandoned once the fishing job was completed.

Although designated as standard fishing tools, the items sold by the various supply houses such as Oilwell were not by any means used exactly for the specific purpose for which they were advertised. Many of them were modified on the job to fit the particular problem presented. By far the greatest problem encountered by the cable tool rigs involved lost manila rope or steel cable drilling line from which was suspended the drilling string. When one of those lines broke or for whatever reason got lost down the hole it had to be fished out. The most common tool used for that purpose was a spear.

The simple fishing spear was just what its name indicates. It was a long shaft from three to ten feet in length with a series of barbs welded to its sides facing toward the top of the tool. When the spear was lowered into the tangled mess of a broken drilling line at the bottom of the hole the barbs captured the line as the spear was withdrawn. Sometimes the single shaft spear would not grasp the lost line tightly and it slipped off the barbs. In that case there were spears featuring two or possibly three shafts arranged in a circle with the barbs welded to the inside of the circle in order to get a better grip and prevent losing the line through slippage.

Other implements for handling lost lines were the knife and the hook tools. The hooks worked similar to the spears only they were shaped like a fishhook. The knives on the other hand were simply designed to cut the drilling line in case it was so entangled the spears could not pull it out of the hole. Sometimes a combination knife and hook tool was used so the line could be grabbed by the hook and pulled to the inside of its bend, where there was a sharp cutting edge. Once the line was cut away from the tangled mess it could be fished out of the hole in smaller lengths. Also sometimes the drilling string became stuck fast, in which case those cutting tools were used to shear the drilling line as close as possible to the drilling string so a whipstock could be set to drill around the offending items.

Beyond drilling line retrieval tools there were a variety of grabs utilized to remove various cable tool items lost downhole. In the case of a string of tools lost but not stuck beyond removal there were several overshot tools that could be lowered over the string and when pulled upward would tighten around the jars—or whatever the top lost tool was—and pull the string out of the hole. Then there was the bailer grab, which was simply a tool similar to a two pronged spear without the barbs. At its bottom was a hinged pin that, when lowered over the bail of the bailer, would swing open and once past would drop back and latch into place, allowing the bailer to be withdrawn from the hole.

Those then were the basic tools used for fishing cable tool wells, along with a host of variations. They were all simple, common sense solutions developed over the years by hundreds of unheralded drillers, tool dressers, and a variety of other oilfield hands. As already mentioned there were literally thousands of variations on those basic tools all designed for problems encountered as well as to suit the particular inclinations of the fishermen who employed them.

When rotary rigs entered the mix about 1894 the downhole fishing problems tended to change somewhat with the advent of the new technology. The lost cable problem practically disappeared with the advent of the rotaries due to their using pipe instead of cable, but the numbers and variety of items lost downhole was absolutely amazing. They ranged from a roughneck simply dropping a wrench in the well bore to bit cones being broken off or maybe the drill pipe being twisted off.

It is from those types of incidents that have fostered some of the best illustrations of oilfield culture. For example the story of the boll weevil who dropped a wrench into the well bore that resulted in a five day fishing job. When the battered tool was finally retrieved the driller handed it to the hapless hand and proceeded to give him a real oil patch dressing down. When he was through the driller told the man he was fired, whereupon the roughneck looked the driller right in the eye and pitched the tool back into the hole. Some say that indicates the graduation from boll weevil to hand, but I can guarantee you it would cause a fistfight right then and there on the rig floor. Then of course there is the term “twisting off” in regard to accidentally severing the drill pipe. That term has come down over time to describe anything a hand might do to cause him undue grief, usually things involving imbibing large quantities of alcoholic beverages.

But I digress. Back to the subject at hand of fishing on rotary jobs. One of the most frequently utilized tools, at least in those early days, was a device called a junk basket designed to remove small objects lost downhole. A junk basket was constructed by cutting slender fingers in the sides of a piece of pipe, fastening it to the drill pipe in lieu of a bit, and lowering it into the hole until it touched bottom. Then the pipe was slowly rotated and weight gradually applied to the drill string. The weight increase and rotation caused the fingers to collapse inward and hopefully clutch the fish within its grasp. Over time that crude device was engineered into a more sophisticated tool, causing it to remain an important fishing tool for many years. In later times powerful magnets were sometimes attached to the bottom of the drill pipe in an effort to remove small items lost downhole.

The most serious of the fishing jobs, like those of the cable tools, revolved around lost suspension devices, which in the case of rotaries was drill pipe instead of cable. In the case of stuck pipe, either drill pipe or casing that could not be withdrawn from the hole, it might be necessary to save as much of the stuck pipe as possible. In the very earliest days that was accomplished by a nitro shooter lowering a shot inside the stuck pipe and shooting it apart. Or a device called a cutter could be lowered into the hole and actually cut the pipe apart. In either case the well might be saved if, after the severed pipe was removed, it was feasible to back uphole a little ways and use a whipstock to deviate the hole enough to bypass the stuck pipe. Otherwise the well was simply abandoned and at least some valuable pipe was saved.

The problem more often associated with lost pipe is that it is twisted off at some point downhole. In that case it is never certain what sort of situation exists at the bottom of the hole in regard to just exactly what is sticking upward for the fishing device to grasp. It might be a jagged piece of pipe, it might be a smooth surface, it might be leaning one way or another, it might be open, it might be collapsed, or whatever. So an important aspect of the fishing process is to discover what is the exact disposition of the object, which in turn will help determine the type of tool needed for the job.

Sometimes a heavy lead plug is lowered into the hole to get an impression of the nature of the top of the fish. If it is retrieved and the fish is shown to be all ragged and bent and generally a mess, as is often the case, it is possible to lower a special tool to grind the item down to a manageable size. When it is reasonably clear what the situation is, there are a variety of tools that can be utilized. They generally fall into the category of undershot or overshot in nature. That is, the undershot, which is lowered inside the offending pipe, or the overshot, which is lowered over the outside of it. Once in place those items have a variety of grabbing mechanisms to grasp and hold the pipe while it is removed from the hole.

Regardless of the exact nature of oilwell fishing jobs, two things are certain. First they normally take a long time. At the least a few days and some of them stretch into weeks. The second thing is that shutting down a drilling operation is an expensive operation and the least amount of time it takes the better. Hence the value of a good fisherman who can figure out what is going on way down below the surface.

Bobby Weaver is a regular contributor to Permian Basin Oil and Gas Magazine.