OSHA-mandated flame retardant clothing (FRC) is an apparel trend that hasn’t caught fire—not among the hands who must wear it even during scorching summertime heat—but help is on the way.

Take a typical summer day in West Texas when the thermometer hits a high of 100 degrees (and sometimes higher) and where shade trees are not plentiful. For a crew on a drilling rig, these conditions spell another long sweltering workday and the possibility of heat exhaustion. Throw in heavy clothing and the situation can become very dangerous for the workers.

Adhering to guidelines by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) while maintaining employees’ wellbeing creates a challenge for safety supervisors who try to find the right mix of measures.

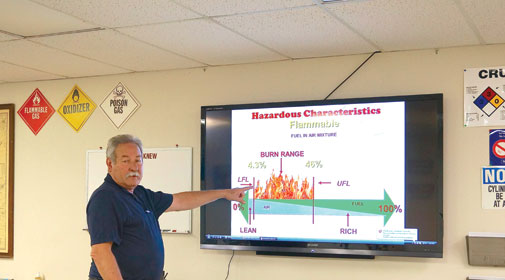

Educating oilfield workers on how to avoid heat exhaustion already had been on the to-do list of employees in charge of safety for their companies. In March 2010, OSHA tossed in a hurdle when it required workers in the oil and gas industry to wear flame resistant clothing (FRC). The reason cited is the chance for flash fires to occur. It’s part of OSHA’s impetus to help prevent injury to employees.

“While the oil and gas industry has worked to reduce the risk of flash fire incidents, these efforts have not eliminated the occurrence of flash fires, nor the resulting burn injuries and fatalities. The use of FRC greatly improves the chance of a worker surviving and regaining quality of life after a flash fire,” noted an OSHA memo from Richard E. Fairfax, director of cooperative and state programs. “Exposure to flash fires can result in devastating burns and death—16 percent of fatalities in oilfields result from fire and explosions.”

In drilling operations, FRC is not needed during initial rig up and normal drilling operations prior to reaching active hydrocarbon zones, according to the OSHA memo. But once the active gas or hydrocarbon zones are reached the potential for flash fires increase and that is when the FRC is required. A compliance safety and health officer (CSHO) will determine if FRC is needed during various well servicing or workover operations and during production-related operations.

Since the appearance of that memo, new businesses have popped up and

Amanda Carroll, employee at the Woods Boots store at Colorado City, shows one of her store’s offerings in their full line of FRC apparel.

existing ones have expanded to meet OSHA’s requirements and to ease the working conditions. Still, workers complain about wearing the federally required workclothes. Manufacturers of FR clothing are producing attire that is lighter weight for summer work. Meanwhile, other companies are building cooling and misting trailers where workers can take a break several times a day from the heat.

“When we talk to the guys in the field and explain the benefits of FR clothing, the guy says he doesn’t deal with flash fires. The guys out there don’t think they

need it; they only wear it because they have to,” said Lenard Garrett, general manager of Lone Star USA Safety and Training in Midland. “There will be guys out there trying to figure ways out of wearing it.

“I understand OSHA’s directive on this,” he added. “They do a lot of research and a lot of good work.” However, there are various issues to weigh. On one hand OSHA is trying to keep more people from suffering burns on the job while on the other hand these FR articles of clothing “cause problems related to heat stress and can affect more people than a flash fire. We see more heat exhaustion cases.”

Since OSHA’s directive was issued, the sale of fire resistant clothing has boomed. Offering FR clothing wasn’t a high priority for Regina Clevenger and her husband Chris when they opened Oilfield Products and Supply in Odessa back in November 2008. Originally, the couple planned to offer a few styles of work clothing and boots along with building rig parts. But the price of oil plummeted and the Clevengers nixed the rig parts.

Two years later, OSHA issued its ruling and the couple heard from more customers seeking FR clothing. “An employee with ConocoPhillips came in and said we needed to have more FR clothing for sale. We now order more FR clothing” than other types, she said.

While they are supplying a need, the feedback isn’t what they expect to hear. “The men [in the oilfield] hate them. They come in griping all the time. I think it [OSHA] is a good rule but I feel for the guys when they have to wear the FR coveralls and it’s triple digit heat out there.”

Since the OSHA ruling was instituted, the price of FR clothing has risen, she noted. “When we started, I could sell an FR shirt for $35. It’s double that now.” Manufacturers cite cotton shortages as one reason for the increase in price.

Many of the FR items are made of cotton with the chemical fire retardant coating the fibers. These items should be laundered in cold water without fabric softener to avoid shrinkage and to maintain the FR coating. However, many workers don’t follow instructions, Clevenger said. “These guys are tired and greasy and they just throw the clothing in hot water and dry them on high heat.”

Some companies are researching fabrics that will be lighter weight and still fire resistant. TECGEN® Select Clothing is one of those lines. Headquarters for the company, Ashburn Hill Corp., are located in Greenville, SC while the manufacturing plant can be found in Angleton, TX. Chris Nowacki, business development manager for TECGEN®, said the fact that FR clothing was bulky, uncomfortable to wear, and conducive to heat-related illnesses prompted his firm to develop a different fabric. Instead of cotton as the main fiber, TECGEN® “is a patented, Bi-regional fiber with unique heat protection capabilities,” according to the website.

Some companies are researching fabrics that will be lighter weight and still fire resistant. TECGEN® Select Clothing is one of those lines. Headquarters for the company, Ashburn Hill Corp., are located in Greenville, SC while the manufacturing plant can be found in Angleton, TX. Chris Nowacki, business development manager for TECGEN®, said the fact that FR clothing was bulky, uncomfortable to wear, and conducive to heat-related illnesses prompted his firm to develop a different fabric. Instead of cotton as the main fiber, TECGEN® “is a patented, Bi-regional fiber with unique heat protection capabilities,” according to the website.

“We have the lightest weight of any fabric for FR clothing on the market,” Nowacki said. “It is 58 percent more breathable than traditional fabrics. It is blended with other fibers that are flame resistant.” Whereas the cotton-based FR clothing is chemically treated to become flame resistant, TECGEN® is resistant “from the inside out. Our FR protection is good for the life of the garment.” He noted that studies show TECGEN® FR clothing is preferred 3 to 1.

One of the oldest manufacturers of work wear, Carhartt, is releasing new lighter weight apparel that meets OSHA’s standards. The company was founded in 1899 by Hamilton Carhartt to produce premium work wear.

“People have been yelling for lighter weight FR clothing for years,” said Tom Kiddle, director of Carhartt’s industrial sales. The biggest obstacle for the manufacturer headquartered in Dearborn, Mich., has been getting the textile to create a fabric that would be lightweight, fire resistant, and meet OSHA standards. “We’ve been in a race for a long time to find cooler fabrics. We’ve always sold to electric utilities and the downstream oil market, refineries. When the OSHA letter hit the industry, our sales spiked. Plus, there is so much going on in the drilling and exploration industry.”

Another catalyst for finding cooler clothing was the military, which is a big user of FR clothing. After the war in Afghanistan began, Kiddle said the military put money into research and development for lighter weight FR clothing.

“Guys were getting blown up by IEDs and the military discovered their troops were wearing polyester T-shirts. These shirts burned to the body and that was a major cause of death. The military has made all the troops wear cotton FR T-shirts.”

Carhartt is releasing a new line of lighter weight FR clothing that wicks

moisture away from the body, Kiddle said. The standard FR shirt weighs about 7 ounces; Carhartt’s new line is 6 ounces. The weight of FR jeans is dropping from 14 ounces to 11 and the design is looser to allow more air flow.

The company’s newest design that Kiddle thinks will be the biggest seller is an

FR T-shirt. “In the old days, guys wore a T-shirt and jeans to work. Then they had to drop the T-shirt and wear a heavy button-down shirt. Now, they can wear a T-shirt again. We think this shirt will change the market,” he said.

Ken Neupert, Permian Region production manager for Apache Corp., said his company doesn’t want any employee “deviating from the OSHA regulation.”

Finding FR clothing that is more comfortable than in the past is getting easier. The FR jeans he wears look and feel the same as his regular jeans, he noted. Many of the workers wear the Henley style or crew neck shirts. “About 50 percent of our people wear these styles.” Apache employees in North Texas add FR treated coats and coveralls for winter. On the personal level, Neupert found that wearing overalls made of Nomex fabric offer him “the most protection and they are very lightweight. I’ve worked offshore overseas and had to wear three weights of FR clothing, depending on the season.”

While the clothing industry has been adjusting to the various demands by the consumers, another industry has evolved to beat the heat in the oilfield: cooling trailers.

Safety Heat Reduction Systems is one of those companies that saw a need and answered it. Tom Dowdy, director of sales and leasing for the company, said his family entered the business when they learned that oilfield workers in FR clothing were suffering from heat exhaustion. The company—which is one of many now active in this niche—manufactures 8-by-16-foot cooling trailers. His flatbed trailers are covered with heavy-duty screens “that don’t transfer the heat” and are outfitted with 22-inch wide benches on each side. A 48-inch evaporative cooler blows cool air onto the people sitting on the benches. Dowdy said the fan can lower the inside temperature to 75 degrees.

These basic trailers cost about $8,500. Some companies also lease cooling trailers. Garrett said LoneStar in Midland has about five trailers to lease. His trailers are enclosed and use refrigerated air. “These trailers are a place where workers can go and cool off, take a break, or eat lunch,” he noted

Dowdy said his firm can’t keep up with the demand, much of which comes from north Texas and Oklahoma. He attributes some of the increased demand to insurance companies requesting their clients use them. “They’re having more employees go to a doctor or emergency room with heat-related illnesses and they see these cooling trailers can help.”

Winter may bring a demand for heating trailers—places where employees can warm up during their breaks on days when the thermometer heads downward, according to Dowdy.

“What we do is give these workers some relief,” he said.

Even with cooling trailers on the wellsite, employees need to follow basic rules to prevent dehydration and heat exhaustion.

As a safety instructor, Garrett emphasizes procedures for employees to follow to alleviate development of heat exhaustion. Heading every safety supervisor’s list is: Drink Lots of Water. No Caffeine. No Energy Drinks.

“Water has been around millions of years. Gatorade only 30 or 40 years,” he said with a laugh. “The body is 70 percent water.”

Energy drinks contain caffeine; soft drinks include caffeine and sugar. “The combination of caffeine and sugar create heat in the body. Energy drinks strain a body,” he explained.

Workers are advised to eat a good breakfast and a light lunch that includes a salad or sandwich. Water should be the only drink of choice. Garrett also nixes the idea of drinking coffee or iced tea on the job. These, too, contain caffeine.

In the evening after work, workers should avoid late night partying and drinking alcohol when they have to work the next day, Garrett said.

Safety experts advise employers to allow their workers to take several breaks each day during the heat. Garrett suggests employees take two or three 10-minute breaks each in the morning and afternoon, instead of a long break twice a day.

The Permian Region production manager of Apache Corp. agreed. “We allow our guys to take as many breaks as often as needed to stay cool,” Neupert said.

The company also believes in constant hydration with water. “When we have had people experience heat exhaustion, we find they were drinking energy drinks or soft drinks. These are dehydrators,” he added. “In our safety meetings we stress the proper hydration.”

On a typical summer day when the sun bakes the ground and everything on it, oilfield employees are finding some relief in their clothing and cooling trailers.