For the first 150 years of the oil industry, rig counts were a strong predictor of imminent production levels and, hence, midstream takeaway capacity needs. One rig punched one hole. The resulting production would immediately flow into a pipeline.

Over the last decade, however, multiple horizontals, multipad drilling, and other outgrowths of the frac revolution have changed the equation. Plus, drilling no longer assumes immediate completion.

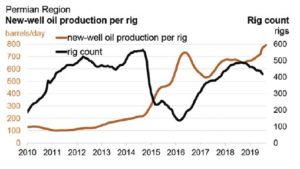

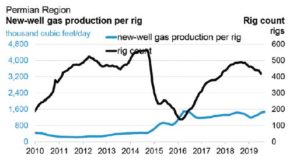

The attached graphic from the U.S. Energy Information Administration shows that the two are no longer as directly connected, at least where typical fluctuations are concerned. It is likely that radical rig count changes would still affect production.

In an extreme example, zero rigs would indeed predict a production drop.

For Steve Reese, CEO of Reese Energy Consulting Company and Reese Energy Training, the better metric today, “is not rig activity, but completions.

“That’s always been the big fallacy, that you can draw rig curves and you can draw production curves. In legacy, vertical pipe times, those curves tended to coordinate better, but today we have all these DUCs [drilled but uncompleted wells],” that don’t go into production right after drilling stops.

Timing of completions depend on each E&P company’s cash flow needs, management decisions based on price deck or hedging strategy, and, third, volume profiles/reserve replacement, Reese said. Some companies dislike DUCs more than others.

“I just see that it’s more of a three-headed monster. I think the number of DUCs, the level of DUCs, and the timing of those wells being completed have more to do with production levels than drilling.”

In the fourth quarter of 2019, falling rig counts in the Permian Basin were attributed to a number of factors, including rising inventory, uncertainties about international economies (which affect demand), and the precarious trade negotiations between the United States and one of its largest export destinations, China. Rising demands of investors, public and private, that producers rein in their spending is another factor.

So what is the actual outlook for Permian production as the year 2020 opens up?

“I think it’s going to be relatively flat unless we have an event that causes prices to go north of 60. The other problem is capital, and that capital is bifurcated between public companies and private equity-backed companies,” he said. “Private equity sponsors right now aren’t all that excited about pouring a bunch more money into some of these expensive horizontal wells. I think a lot of them are going into a cost-cutting and efficiency mode [more] than they are of, ‘Let’s try to drill our way out of this,’ ” Reese said.

For public companies, prices dropped dramatically in the latter half of 2019. On Nov. 1, ExxonMobil announced a 49 percent drop in earnings, a decline caused primarily by lower oil prices. In March 2019, the company announced a goal of producing 1 million barrels per day in the Permian by 2024, an increase of approximately 80 percent. Chevron has announced similar goals.

Whatever current thinking on production levels for 2020, the pipeline expansion is in full swing. Phillips 66’s Gray Oak Pipeline (800,000 bopd) online as of September 2019, Plains All American’s Cactus II (670,000 bopd) online in August, and Epic Midstream’s Epic Crude Pipeline (900,000 bopd) are expected to be operational in January of 2020. Energy Transfer Partners’ Gulf Coast Express was canceled earlier in 2019.

The choking down of investment is not just affecting drilling, it’s changing the paradigm for midstream companies who also rely on PE money, Reese said. This is causing midstream companies to more closely scrutinize greenfield projects, which are more capital intensive than expansions of existing systems. Investors are looking more short-term on ROI for midstream, just as they are for producers.

It has also pared down the field of PE-backed midstream firms. “At one time recently, we had counted up to well over 100 private equity backed midstream management teams in existence,” Reese said. “I think you’re going to see that number continue to dwindle. The midstream industry right now is in the process of sharpening its pencil.”

Some analysts fear that there is an overbuild in capacity coming in the next few years, both in oil and natural gas. With new export facilities also in the works further downstream, Reese does not see an excess of capacity anytime soon. But even if one were to develop, that’s nothing new. In fact, the leapfrogging between supply and takeaway capacity is almost inevitable, he says, due to the long lead times versus the volatility of oil and gas markets.

“This has been happening for years. We did a large study in 2012, when the NGL space was tight, just like oil and gas are now, coming out of the Permian. We looked at all the planned expansions of NGL lines to [Mont] Belvieu and also the fractionation at Belvieu, and they did increase capacity by over a million barrels a day, both on transport and on frac.” All that capacity addition did result in an oversupply for a while.

“But thank goodness it was teed up for what started happening in ’15, ’16, ’17 and ’18 with the increase in drilling.” All of what had been excess capacity was used up, and the facilities were strained to the limit for a couple of years, Reese said, adding, “It’s almost impossible to time that stuff perfectly to where you’ve got a 90 percent load on all these systems all the time. You’ve got to really go out and build the capacity and capture that firm transportation fee, and you’re going to have some lulls.”

Midstream companies protect themselves by getting the capacity subscribed to before building. And there are two aspects to fees: “One is the demand and reservation fee—you pay it whether you have volume moving through it or not—and the second is the fee on the commodity that is moving. So when they build these new pipes they at least have the security of knowing they’re going to have that firm transportation fee whether the pipe’s full or the pipe’s empty.”

Most capital-intensive markets love stability, because that allows budgeting and planning to extend out 5-10 years. But in the last few years, planning 5-10 quarters out should be done with a pencil and a nearby eraser. So the seesaw effect of oversupply—of too little takeaway capacity interspersed with too much—is likely to continue, as most basins, including the Permian, produce much more oil and gas than they can use locally.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

By Paul Wiseman