This image shows the above-the-fold portion of the front page of the Pecos Enterprise on Nov. 3, 1922.

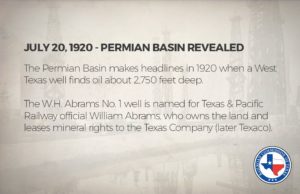

Just one hundred years ago this year, some 19 years following the Spindletop discovery on the Gulf Coast that made Texas the leading oil producing state in the nation, the first successful oil well in what was to become known as the Permian Basin was drilled. At the time the region was viewed as a semi-arid wasteland, a hinterlands known only for a sparse population dependent on the livestock trade. The region was deemed to have little chance of harboring any petroleum potential. All that was soon destined for change. During the 100 years since that first well was drilled, the Permian Basin has come to be recognized as the largest and most prolific oil and gas producing region in the nation.

The Basin is huge by oilfield standards. It extends some 300 miles, from near Lubbock on the north to Pecos County on the south and 250 miles from near Colorado City on the east to the Pecos River valley and eastern New Mexico on the west. It derives its name from a deep subsurface geological basin formed during the Permian period that consists of thick sedimentary rock formations where petroleum exists at various depths across its vast expanse. Consequently, it is not one continuous oil field, as some outsiders envision it, but a series of fields discovered at various times between that first 1920 discovery and the present.

As is true of so many subjects of legendary character—and the Permian Basin’s story is rich in legend and lore—there are various accounts touching upon various dimensions, some of these accounts imbued with more drama than others. The more dramatic accounts have, understandably, received the greater share of publicity. Such is the case with the story of the drilling in 1923 of the renowned Santa Rita #1, which has long been generally accepted as being the discovery well of the Permian Basin. Although that well’s story is an important part of the history of the region, the Santa Rita well was preceded by two others in the long history of oil and gas production in the Basin.

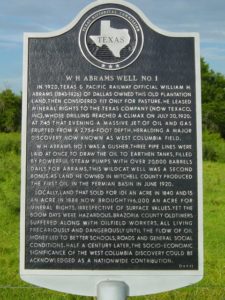

That first commercially producing well in the Permian Basin was part of a statewide search for more oil during and following World War I. What began with salt dome oil discoveries on the Gulf Coast had expanded north and west across the state until by 1918 leasing was begun by the Underwriters Producing Company in Mitchell County on the far eastern side of the Permian Basin. Their first attempt, the Texas Pacific Abrams #1, spudded in early in 1920 about two miles northwest of the little town of Westbrook under the direction of a well known wildcat driller named Steve Owens.

By February 8 the Abrams #1 had reached a depth of 450 feet and had a slight showing of oil. The well was completed late in June at a depth of 2,987 feet and it was scheduled to be shot with nitroglycerine on July 16. On the appointed day more than 2,000 excited West Texas citizens gathered to witness the event and they were not disappointed. The shot blew mud, water, and, more importantly, oil high above the wooden derrick to the delight of all attendees. At the time the Abrams well was touted to be a 2,000 barrel per day producer although it quickly settled into the 100 barrel production range. Nevertheless, the discovery attracted tremendous interest and oil men fanned out across the deserted region in a quest for similar opportunities.

Eventually, the area, known as the Westbrook Field, expanded in size to some six miles long by to two miles in width which over the following nine decades produced more than 100 million barrels of oil while prompting the development of 21 other small fields in Mitchell County. By 1922 production from the Abrams discovery caused H.L. Lockhart to build the first commercial pipeline in the Permian Basin. Two years later, after production warranted it, the first oil refinery in the Permian Basin, the Col-Tex facility, was built on a 175-acre site just west of Colorado City. That refinery remained in operation until 1969 and was dismantled in the early 1970s.

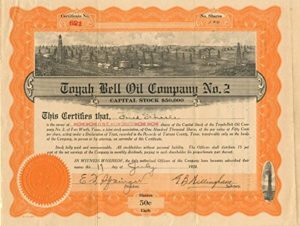

Excitement created by the Abrams discovery caused oil fever to spread across West Texas and a year later that activity resulted in a second commercial discovery on the far western edge of the Basin in Loving County. That area was then, and still is today, one of the most sparsely settled sections of the state, that is if you disregard the massive influx of temporary oilfield workers caused by the Delaware Basin play of the last few years. Back in 1921, when J.J. Wheat and Balden Ramsey organized the Toyah-Bell Oil Company and leased acreage on the Russell Ranch about one mile east of the present town of Mentone, the county had so few residents that attempts to organize it back in the 1890s had to be abandoned due to having only a score or so of residents. It was not until 1931 that the county was reorganized although it continued to struggle to maintain a population hovering around the 100 mark. That situation continues to the present when the 2010 census indicated only 82 residents.

In the summer of 1921 the Toyah-Bell Oil Company spudded in on the Russell #1. By December of that year the completed well was flowing enough oil to be considered a commercial success. At that point the company name was changed to the Ramsey Oil Company, the company signed a contract to deliver oil to the Rio Grande Oil and Refining Company at three dollars per barrel, and they built a four-inch pipeline to the Pecos River Railroad siding of Arno a few miles away. Ultimately, enough wells were drilled in the area around Mentone to form the Wheat Oil Field, which managed to continue operating with a small production until the present day.

Those discoveries in 1920 and 1921, which created the region’s first commercial oil pipeline and its first oil refinery, were on opposite sides of the Permian Basin but the discoveries were a portent of things to come, although at the time there seemed to be little connection between the two, considering the more than 200 miles separating them. How that space became filled with producing oilfields to create the massive Permian Basin oil production of today is a fascinating story built around a host of legendary events and illustrating the changing technology over time that allowed the area to prosper.

The West Texas of the Permian Basin was then, and remains today, a harsh and unforgiving land where water is rare and precious and everything that grows seems to have thorns of one kind or another. That landscape presented those early oil men with numerous difficulties unique to the region. To begin with, there were no paved roads in the entire space and those that existed were little more than sandy tracks leading to lonely ranches scattered at great distances apart. Further, internal combustion powered trucks were in their infancy and totally unsuited for work in the area. Freight was delivered into the area by rail to the railroad siding closest to a discovery, where it was unloaded and transported by animal-powered vehicles to the work sites. One of the most colorful oil patch sights of those days were the locations where thousands of horses and mules were quartered to handle transportation needs.

In those first days all rigs were powered by steam engines, which required water for the boilers that provided the steam to run the engines. Getting the water to power those operations was a continuous problem in the arid environment. Electrical generators were just coming into vogue in those first days of the Permian Basin development so most rigs were lit by “yellow dog” lamps, which were nothing more than small open-flamed lamps with a reservoir containing oil and two spouts stuffed with rags that were lit to provide the source of light for night work. The rigs were all cable tool operations of wooden construction with derricks in the 70- to 80-feet-high range whose maximum efficient drilling depth was in the 4,000- to 5,000-foot range with the usual well being completed in the 3,000-foot-or-less range.

One of the major problems facing the opening of a new oil region in such a desolate region was that all the work was dependent upon heavy use of manpower. Drilling crews required a significant number of workers, but that paled in comparison to the huge needs required to service the primary purpose of drilling wells. First on the scene were large numbers of teamsters needed to transport freight, grade roads, build drilling locations, and all the other preparatory work for drilling operations. Then the rig builders, whose crews usually numbered in the five to eight man size, had to build each wooden rig on every location. Those derricks were usually left on site to serve pumping and well servicing needs although they were sometimes dismantled and rebuilt on other locations or even more rarely skidded to a new location. Once the drilling crews began work there were the numerous oilfield supply people rushing to and fro to keep them in “rope, soap, and dope” and once again the freighters with their large teams of draft animals came into play to transport all that material.

By the time wells were completed the tank builders had to build field tanks for immediate storage as well as the huge 55,000 barrel tanks at the tank farms for pipeline storage. Then the pipeliners arrived like swarms of locusts in 100 man crews to lay lines out of the area or to the various railheads where oil was shipped in railroad cars. There were the roustabouts and connection crews to supply general labor and the pumpers to take care of the producing wells. Altogether it took a myriad of jobs to create an oil field and keep it operating in an efficient manner.

All that manpower operating on a 24-hour basis attracted thousands of workers to descend upon the region over those first years following the initial discoveries and the others that soon followed across the region. The problem that arose is that there were vast distances to serve and hardly any towns. How to feed, clothe, house, and entertain such a huge influx of people into a region that was practically void of a population was perhaps the greatest test for the region over time. In the very earliest days work crews lived in tent camps or small skid mounted sheds adjacent to the drill sites and other construction areas. A few towns popped up in the fields and they were, for the most part, temporary tent and shack type communities consistent with the nature of traditional oil boom towns preceding them.

The almost total lack of proper housing caused the oil companies operating in the region to develop a “camp” system of housing for their permanent employees. Those camps ranged in size from a few well built houses up to a virtual community of more than a hundred that had all the amenities of housing in towns of the time. The camp system became one of the prime characteristics of the region and it continued in operation until the 1960s when improved transportation allowed the workers to live farther from their work sites.

So it was that two oil discoveries on opposite sides of the Permian Basin during the first couple of years of the 1920s set the stage for the future development of the phenomenon that became the state’s most prolific oil and gas production region. The Basin’s story is one of creating a tremendous economic resource in the face of overcoming great geographic and technological challenges during its first one hundred years of dedicated activity.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________

Bobby Weaver is a regular contributor to Permian Basin Oil and Gas Magazine. He is the author of Oilfield Trash: Life and Labor in the Oil Patch.