Although completion of the Santa Rita #1 well in Reagan County in 1923 was preceded by the Mitchell County Abrams #1 (1920) and the Loving County Russell #1 (1921), firsts do not necessarily denote the most important. The Santa Rita well, which was in the same 100-barrel production range as those which preceded it, received a great deal more publicity and ultimately caused a flurry of activity in the southern portion of the Permian Basin in the early and mid-1920s. That massive boom is what got the Permian Basin off to the roaring start that ultimately resulted in its becoming the giant oil and gas production region it is today.

The story of the drilling of the Santa Rita #1 is the epitome of the boldness, tenacity, ingenuity, and just plain old “luck of the draw” that has come down as the hallmark of those working in the industry today. Like all good oil patch yarns it begins with leasing. In January of 1919 Rupert P. Ricker of Big Lake made application for leasing rights on 431,360 acres of Texas public lands in Reagan, Upton, Irion, and Crockett Counties, generally known as university land, set aside for the support of the University of Texas and later also for Texas A&M University. With only ten days left to raise the ten cents per acre leasing fee, Ricker, who had been desperately searching for and failing to find backers, sold his leasing application to Frank P. Pickrell and Haymon Krupp of El Paso for the sum of $2,500.

The story of the drilling of the Santa Rita #1 is the epitome of the boldness, tenacity, ingenuity, and just plain old “luck of the draw” that has come down as the hallmark of those working in the industry today. Like all good oil patch yarns it begins with leasing. In January of 1919 Rupert P. Ricker of Big Lake made application for leasing rights on 431,360 acres of Texas public lands in Reagan, Upton, Irion, and Crockett Counties, generally known as university land, set aside for the support of the University of Texas and later also for Texas A&M University. With only ten days left to raise the ten cents per acre leasing fee, Ricker, who had been desperately searching for and failing to find backers, sold his leasing application to Frank P. Pickrell and Haymon Krupp of El Paso for the sum of $2,500.

The new owners had better credit than Ricker. They borrowed the money to pay the leasing fee, abandoned Ricker’s original plan of utilizing the land for grazing purposes, and formed the Texon Oil and Land Company. With only two years to show the state good faith use of the property or lose the lease, they began to sell stock in the company. Unfortunately, stock sales did not proceed rapidly enough to begin drilling before the January 9, 1921, good faith deadline, so they went to plan B. That involved setting aside 16 sections of university land which they called Block #1 in which they sold “certificates of interest” that entitled the holder to a small interest for a mere $200 per certificate. Over about a year’s time they raised $100,000 despite the fact that the site was well over 100 miles from the nearest known oil production.

As the deadline grew near Pickrell used part of the funds to buy a quantity of cable tool drilling equipment and had it shipped to a railroad siding called Best on the Kansas City, Missouri, and Orient Railway about 12 or 14 miles west of Big Lake in Reagan County. With only a few days left before the leasing rights expired Pickrell decided to ignore the remote location chosen by the geologist he had hired (most in the oil business in those days didn’t trust geologists anyway) and drill adjacent to the railroad. The site he chose was 174 feet north of the Kansas City, Mexico, and Orient Railway at the spot where he had unloaded the drilling equipment. About noon on January 8, 1921, just one day before lease contract expired, he hired a crew that set up a portable drilling rig on the site to drill a water well designed to service the planned drilling operation. By sundown it was operational and sometime after dark Pickrell spied a vehicle’s lights moving in the distance. He flagged the car down and persuaded its two cowboy occupants to sign affidavits swearing that work had begun on the well prior to midnight on January 8, which proved that he had met the deadline and thus saved the lease.

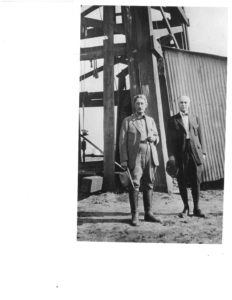

In June of that year a rig building crew was hired to camp out on the site and build the derrick and associated wooden drilling portions of the rig as well as two boxcar-type “shotgun” houses to serve as the drilling crew’s living quarters. By the time the rig builders finished Pickrell had also hired an experienced cable tool driller named Carl Cromwell for the princely wage of $15.00 per day plus stock in the enterprise. The driller moved his wife and small daughter into one of the houses, used the other as living quarters for any local help he could hire provided he could find them, and over the course of the summer in that isolated and lonely spot he managed to cobble together the various pieces of drilling equipment scattered randomly around the location. It took him until August before he had the drilling rig assembled and ready to go.

The Santa Rita #1 was spudded in on April 7, 1921, when Pickrell, in one of the most unusual ceremonies in recorded oil patch history, climbed the derrick, cast a handful of dried rose petals into the air, and dubbed the well the Santa Rita. That unusual event was precipitated by a request by some investors, as he recalled in a 1969 interview:

The name Santa Rita originated in New York. Some of the stock salesmen had engaged a group of Catholic women to invest in the Group 1 stock. These women were a little worried about the wisdom of their investment and consulted with a priest. He apparently was also somewhat skeptical and suggested to the women that they invoke the help of Santa Rita who was the Patron Saint of the Impossible! As I was leaving New York on one of my many trips to the field two of those women handed me a sealed envelope and told me that the envelope contained a red rose that had been blessed by the priest in the name of the saint. The women asked me to take the rose back to Texon with me and climb to the top of the derrick and scatter the rose petals, which I did.

Cromwell continued to drill on the well with only sporadic help from itinerant cowboys or anybody else he could cajole to work. It was not until January of 1922, when an experienced cable tool man named Dee Locklin, who was driving overland from the new discovery out in Loving County, happened to spot the rig running out in the back end of nowhere. When Locklin stopped to investigate, Cromwell hired him on the spot. Locklin brought his wife out to the location where they lived in the second shotgun house while he worked as tool dresser for the 18 months it took to complete the well.

Drilling the Santa Rita #1 was the classic “poor boy” operation. During the course of its drilling progress averaged less that five feet per day. The job was plagued with almost every problem you could imagine, ranging from a variety of fishing jobs to never being able to keep the rig running on a 24 hour schedule. The truth of the matter is that the rig was down almost as much as it was running. Additionally, Locklin remembered going as long as three or four months between paychecks.

Drilling the Santa Rita #1 was the classic “poor boy” operation. During the course of its drilling progress averaged less that five feet per day. The job was plagued with almost every problem you could imagine, ranging from a variety of fishing jobs to never being able to keep the rig running on a 24 hour schedule. The truth of the matter is that the rig was down almost as much as it was running. Additionally, Locklin remembered going as long as three or four months between paychecks.

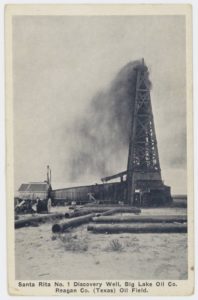

Finally, on the afternoon of May 23, 1923, the two-man crew got a showing of oil and shut the operation down for the day. The next morning, about seven o’clock, as the “toolie” and the driller were having breakfast in their respective houses, they heard a loud roaring noise. Upon rushing outside they witnessed oil pulsing from the wellhead. It would ebb and flow several times and then eventually blow over the top of the derrick. Then it would drop to just a trickle before it started the process over again in a routine that took about 12 to 14 hours to complete. It took two weeks to bring the well under control and in the interim it filled both the 250-barrel tanks on the location and flooded the surrounding countryside with oil. It has been estimated that the Santa Rita #1 flowed between 30 and 100 barrels per day during that time although it finally settled in at around the 100-barrel mark. It was not the biggest well ever drilled, but it proved that there was petroleum wealth out in those trackless wilds of West Texas and subsequent activities in that immediate area soon expanded those activities into an oil boom situation.

Meanwhile, back on the afternoon of the 23rd, when Cromwell and Locklin got that first showing of oil, they, in the entrepreneurial spirit of the time, devised a scheme. They knew that they had a showing of oil that might turn into a real find so they decided to cash in on the situation before the well actually blew in and word got out. In a 1970 interview Dee Locklin explained:

We closed down and nailed the rig up (nailed the door down), set the bailer in the hole, and we were not going to work the next day. We were going to buy up some leases around the county, which we did. We did that because we knew we had oil, we didn’t know how much, but we actually knew that much before the well actually began to blow. Then the well blew in. There wasn’t anything we could do about it. We just had to go on. We got 20 or 30 sections, I can’t remember for sure. We got it all in one day. It was quite a bit of country to cover, but we made all the ranches and made the deal right there. Then we went over to the courthouse, which was at Stiles at that time, and had the papers drawn up.

Although they worked fast before word got out about the successful well the driller and his tool dresser never realized any production off the leases they acquired that day although they did make a tidy profit on the deal by reselling the leases shortly afterward.

Bringing in a well and realizing a profit on the discovery were two entirely different situations. Although the potential was great, Pickrell immediately realized that he and Krupp did not have sufficient capital to develop the acreage under their control. It was not until five months later, in October of 1923, that he persuaded the flamboyant independent Pennsylvania oil man, Mike Benedum, to become involved. Benedum formed the Big Lake Oil Company and began to develop the field. His activity caused major oil companies to join the fray and within a year the boom was on and within two years it had spread across that entire section of the Basin.

The first royalty payment to the University of Texas in the amount of $516.53 was paid in August of 1923. Since then oil and gas royalties from state university lands have helped make both the University of Texas and Texas A&M University the best funded educational institutions in the state. In 1940 the original equipment from the Santa Rita #1 was salvaged and stored when the Marathon Oil Company replaced it with an all-steel pulling derrick and associated equipment. The original equipment from the well was preserved through the efforts of the Texas State Historical Association, which in the 1950s had it installed on the campus of the University of Texas in recognition of its importance to education in the state. The Santa Rita #1 was taken out of service and plugged in 1990 after 67 years of service.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Bobby Weaver is a regular contributor to Permian Basin Oil and Gas Magazine. He is the author of Oilfield Trash: Life and Labor in the Oil Patch.