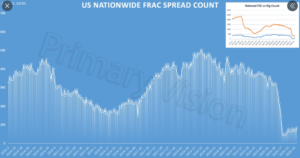

This chart by Primary Vision shows the movement in frac spreads over recent years. Frac spread count has become a good indicator of activity—and confidence—in oil and gas.

Was there ever a more schizophrenic year for oil and gas? The tumults of 2020 have kept markets in disarray and left analysts and observers divided.

Opposing forces keep tugging at the industry, hindering any straight-line improvement.

On one side, there is the Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) movement, with its emphasis on what it defines as sustainability. The ESG forces that have surged into oil, mainly into Big Oil, have dampened enthusiasm for oil’s long-term robustness, ironic as that might sound. While ESG falls short of being a full-bore “keep it in the ground” influencer, the movement nonetheless buys into climate change and the Paris Accord and all that goes with that. This positioning can’t be helping oil win over any enthusiasm from the public or from capital markets.

Meanwhile, in opposition, there is simply the market forces of normal supply-and-demand. Oil and gas are commodities that, left unhampered by politics and protests and investor partisanship, ought to be able to steadily gain ground in a world that can always use more inexpensive, reliable, efficient energy. Or at least can use more as soon as current oversupply gets worked off.

Perhaps yet another factor could be layered across these two. That factor would be one of underappreciation of the fact that the oil and gas industry is a commodity market and deserves to be looked upon as such. So many of the knocks against oil come from parties who seem to look upon oil as being a typical (that is, non-commodity) product, like a retail product. It’s not totally fair to oil when oil companies are held accountable for poor earnings that are the result of global dips in the price of the commodity.

Such risks don’t come into play—at least not so much—with typical manufacturers or providers of services in the non-commodities fields. There, a bad performance is purely a bad performance.

But a crash in the price of oil or gas can make genius look like incompetence. Likewise, a sudden and prolonged dip in the price of a commodity can bring hard scrutiny to business practices. If the critic makes allowances for the fluctuations of the commodity, then it is justifiable. If the critic ignores the commodity and looks only at income statements and balance sheets, then the conclusions reached could be short-sighted.

That’s because commodities are largely self-correcting. They are driven by supply-and-demand factors that producers have no influence upon, or that they have very little influence upon.

Think of any oil CEO who has been excoriated in 2020 for poor performance. Chances are, the books would have looked entirely different, and remarkably better, if the commodity itself were trading at $60 a barrel, rather than at $30 a barrel. And can we blame the CEO alone for that?

Moreover, commodities are cyclical in ways that most other goods and services are not. That is, a world that suddenly penalizes all producers with a crushing decline in commodity prices is a world that will pay the price, given enough time, by contributing to huge shortfalls of product. When supplies tumble low enough, demand rockets skyward, and with it, prices.

Commodities markets have that kind of resilience. The harder they are hit, the harder they rebound. That fact seems lost on the world of 2020. We see many in Wall Street writing off oil and gas as though its current economics are a trustworthy predictor of its future economics.

We see many observers confidently predicting that shale will never again reach the heights it reached in the past decade.

Such assumptions fail to take into account all the variables. One such variable is the likelihood—or unlikelihood—of other energy sources replacing oil and gas economically and safely.

But the point here is not to make oil’s case as an energy source superior to renewables. The point is to defend oil as an industry more viable than its detractors would admit.

At the current time, we see the industry at low ebb.

Rig counts have fallen to dismal numbers, and the same now is true of frac spread counts.

The United States ended August with 85 active frac spreads. A frac spread is, in essence, a frac fleet. It’s all the heavy equipment, personnel, and hardware needed to frac a well. (See illustration for an indication of just how severe this drop has been.)

Such numbers are a function of the low price of crude oil itself. But let’s remember that we are dealing here with a commodity, and commodities have a special kind of cyclicality that other niches do not possess.

In other words, the greater the pressure placed upon oil and gas, the greater the depths to which it is taken, the more pronounced the rebound.

Already we are seeing some stirrings of an upturn. Let’s consider some recent developments in oil and gas.

On August 16, OilPrice.com published an article headlined, “Oil Prices Rebound as U.S. Inventories Dwindle.” That article cited an Energy Information Agency report that “showed that commercial crude inventories continued to shrink, with a drop of 4.5 million barrels, week to week, to stand at 514 million barrels.”

On that same day, SeekingAlpha.com, writing about stocks, said, “Oil Sector Ready to Double.”

So some sources already are looking beyond the current dismal times and seeing cause for optimism.

In contrast, let’s look back some nine months, to early 2020. A January article on SeekingAlpha.com, “Abrupt Reversal of Shale Oil’s Fortunes,” had this to say:

“The second shale boom was due to 500 frac spreads paid for in the first; now only 300 are left, and 200 were sold for scrap.” [That was then—as we stated above, the frac spread count has plummeted to 85.]

The article went on:

“No one is buying new. The prediction of a 900,000 bbl/day surge in production in 2020 is physically impossible. When the market finds that out, there will be a reset in oil prices…. Schlumberger and Halliburton have given up on frac’ing. They are headed offshore. That’s where the action will be in 2020.”

That was the sentiment back in January. And many readers will recall the talk in late 2019 that onshore shale had seen its best days and was headed to an irreversible decline.

All of this talk seems to be rooted in an idea that oil and gas behaves like consumer goods. Or that oil and gas balance sheets and income statements can be read precisely the way that a consumer goods company’s financials can be read.

Oil and gas have an X factor in their favor, and that X factor is the tremendous lift that a commodity price can give to an industry.

It was only 5-6 years ago that oil traded at $100 a barrel. If oil recovered even just half of the loss it has seen, the industry becomes an entirely different thing than it is at this moment.

ESG and Wall Street notwithstanding, oil and gas has a bright future. Not just in some distant time, but likely as soon as 2021.

Only time will tell, but that’s true for all businesses.

Here’s wishing the Basin good fortune in getting back on its feet and proving its critics wrong.