“It’s not easy being green,” Kermit the Frog famously said, and many oil and gas producers feel the same way about ESG and the growing number of environmental regulations. ESG is short for “Environmental, Social, and Governance”—three non-financial factors that investors increasingly take into consideration when investing in companies, including energy companies. And it’s not always “easy” to be “green,” at least not by ESG’s strictures.

But the truth is, says Grant Swartzwelder, co-founder and president of ESG Dynamics, that an ESG program can offer a number of economic benefits that can help it pay for itself. Operational efficiencies, recouping methane for sale, and increased investor interest are at the top of that list.

“First are the pure economics of it,” Swartzwelder said. “When natural gas is now at $6-7 an mcf, and this vapor [at well sites], because of its heavy BTU content, is really worth more than that because it’s a more valuable gas, the basic economics of capturing this gas as opposed to flaring it or letting it vent is more pronounced now than ever before.” He feels it was always worth capturing and selling, but now it is even more profitable, along with being helpful to the environment.

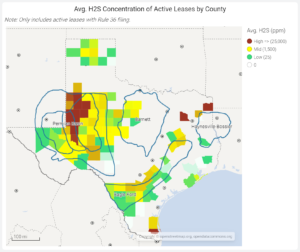

A second benefit involves site safety. “As you’re capturing this vapor and tightening up your system, you’re minimizing the amount of flammable vapor on location.” That reduces the risk of fire and other safety issues, since those vapors can be toxic even if not ignited. Toxicity is especially an issue in the Delaware Basin, which is known for producing significant amounts of toxic and deadly hydrogen sulfide (H2S).

A second benefit involves site safety. “As you’re capturing this vapor and tightening up your system, you’re minimizing the amount of flammable vapor on location.” That reduces the risk of fire and other safety issues, since those vapors can be toxic even if not ignited. Toxicity is especially an issue in the Delaware Basin, which is known for producing significant amounts of toxic and deadly hydrogen sulfide (H2S).

Keeping the system closed by reducing leaks protects site personnel from this toxic substance.

On that topic, Swartzwelder noted that the biggest cost saving comes in preventing incidents. A single accident can come with a huge cost in dollars and in health. While H2S deaths and serious injuries are rare, they do still happen every few years, and a tight system for transporting gas can greatly reduce that risk.

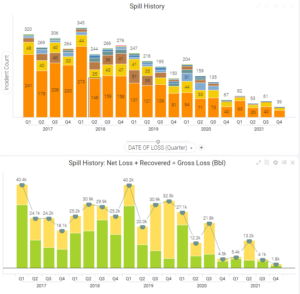

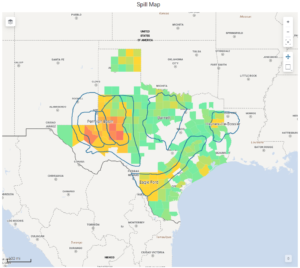

Plus, the cost of a an accident is not just monetary, although fines and cleanup can be very expensive—damage to a company’s reputation, landowner relations, public relations, and other intangibles can be significant.

“It only takes a minimal number of parts per million of H2S to cause a major effect” or a death, Swartzwelder pointed out, and many leaks contain hundreds of times that amount.

The third benefit in Swartzwelder’s view involves the company culture. “If you’re really taking care of the vapor and making sure that your facilities are plumbed correctly and that you’re documenting everything, I maintain that that helps create a culture where you’re making sure you’re taking care of your business correctly [in other areas],” he said.

While monetizing or accounting for it is difficult, a culture of care and safety can give employees a feeling of confidence in the company, helping with employee retention. Fixing leaks, reducing H2S and other measures “Should create a more positive work environment,” he observed.

From the PR side, perhaps the biggest concern is the fact that environmental advocates are scouring the landscape for negative stories about oil and gas, and some would love nothing more than to learn of an accident and noise it abroad.

Even without an accident, there can be bad publicity if a facility is leaking methane. Some groups conduct drone or fixed-wing flyovers with vapor-detecting cameras aimed at well sites, looking for the presence and amount of leaks.

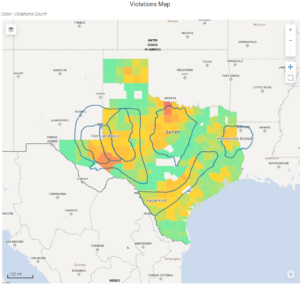

Self-reporting options are available through the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ), the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Texas Railroad Commission where operators can self-report emissions data. This way, good reports can also be part of the record. Acknowledging the fact that compliance with this reporting is currently spotty, Swartzwelder recommends operators up their game. “That’s the first step that the industry needs to take, is to be able to audit and to look at their data and make sure they’re putting it in.”

Much of the data that is available, he noted, shows that “The Permian Basin is actually doing a good job” at reducing methane leaks. He feels the industry could be better overall at calling attention to its ESG successes, because environmental groups are sure to point out any mistakes. “There are a lot of things that the industry’s doing well at, and we just do a horrible job of letting folks know about it.” He listed the decrease in flaring since 2020, decreasing emissions, and venting, among others. “If you don’t tell anyone, it allows other people to create the narrative.”

A Capital Idea

Operational efficiencies and the ability to send more gas into the sales pipeline are among the front-side benefits of being green. On the backside is ESG’s influence on capital and investors, and Swartzwelder says that message is also getting through to producers. “The prevalent players out there [in capital markets] are very concerned about ESG because their investors are very concerned about ESG. They are pushing that down onto all the operators, forcing them to be much more focused on ESG, not only in reporting but also in how they conduct their business.”

Publicly traded companies face similar forces. Companies like Pioneer and Diamondback are looking for Net Zero and ESG goals due to pressure from those investors, as are the giants like Shell and ExxonMobil.

M&A activity is also influenced by ESG, especially if an operator is interested in selling to a large independent or a major. The larger companies, already on the ESG train due to investors, will be more interested in a property whose ESG metrics are at least equal to, or better than, their own in ESG and reporting, than one that would require extensive effort and expense to be brought up to the standard.

M&A activity is also influenced by ESG, especially if an operator is interested in selling to a large independent or a major. The larger companies, already on the ESG train due to investors, will be more interested in a property whose ESG metrics are at least equal to, or better than, their own in ESG and reporting, than one that would require extensive effort and expense to be brought up to the standard.

“We’re seeing a lot of opportunity, through our work at ESG Dynamics, to help potential sellers know how their metrics and analytics look, so they’re better than the potential buyer. Then they’re able to go and say, ‘We’re actually accretive to your company’s performance.’” If the metrics do not measure up, the analysis allows them to upgrade their metrics to make them more attractive before putting the property on the market, Swartzwelder said.

What’s in a Report?

At noted above, ESG reporting itself is an issue because there is no single agreed-upon standard for what should be included or how it should be calculated. As a result, various environmental groups and agencies that endeavor to rank corporations on their ESG scores often publish very different top 10 lists, creating controversy such as that involving Tesla in May. That month the S&P 500’s ESG index dropped Tesla and 34 other companies from its list, prompting Tesla CEO Elon Musk to declare on his Twitter account, “ESG is a scam. It has been weaponized by phony social justice warriors.”

While a single ESG reporting standard might have merit, even that would be hard for industry and environmental groups to agree on due to their varied and often opposing viewpoints.

In March 2022 the Securities and Exchange Commission announced plans to add ESG reporting to its registration statements and periodic reports that would include “information about climate-related risks that are reasonably likely to have a material impact on their business, results of operations, or financial condition, and certain climate-related financial statement metrics in a note to their audited financial statements. The required information about climate-related risks also would include disclosure of a registrant’s greenhouse gas emissions, which have become a commonly used metric to assess a registrant’s exposure to such risks,” according to an SEC statement.

This plan has created its own controversy, with Swartzwelder noting that the agency has extended the public comment period in order to allow more input from all parties. But the SEC is large enough that whatever form their final documentation takes, it is likely to greatly influence how all companies do their ESG reporting.

Whichever side of the green debate an entity finds itself on, there is no question that ESG concerns are becoming a necessary part of daily business. While many consider any kind of reporting to be onerous, Swartzwelder and others see benefits both economic—selling more product at high prices—and relational, in boosting safety and cleaning up both image and workspace.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Paul Wiseman is a freelance writer in the oil and gas sector.