After decades of resisting change, the oil patch in recent years has begun to embrace—and even seek out—new technologies that reduce overhead, boost efficiencies, and improve production, among other things, at least some of the time. One Houston company has recently purchased a developing technology it hopes will reduce flaring in the Permian and elsewhere in the world, turning that gas into sellable and usable product. Another has released a software platform that aggregates all data from the wellhead to the back office to give decision makers more complete data.

The first company, ENG, is a longtime engineering firm that has in recent years expanded into other areas including field services, fabrication, automation and others. They recently acquired Calvert Group Belgium “and its exclusive license to patented gas to liquids [GTL] technology to convert flare gas and stranded gas to synthetic liquids such as crude oil or diesel,” says a May 2022 press release. The small-scale process can also convert flare gas to naphtha.

Plants will be manufactured offsite and designed for quick assembly onsite and for mobility. They’ll come in three sizes—making 25, 50, and 100 BPD of liquid. The cost is expected to be around $4 million each, with an expected life span of about 20 years. None are yet deployed, but ENG CEO Mark Hess expects to install the first one in the Middle East in mid-2023.

He notes that his company felt the purchase was a good fit as they expand from just engineering into field services—especially in the Permian Basin. “If you look at what this technology is—small scale gas-to-liquids [conversion] for flare sites and stranded gas—that fits very well within the issues our clients are having, not only out in the Permian, but across the globe.”

Before the pandemic-related shut-ins of wells, some experts estimated that Texas producers flared enough stranded natural gas in any 24-hour period to generate the daily electricity needs for the entire state. While flaring slowed in 2020, oil production since December of 2021 has returned to record levels, with natural gas coming along for the ride.

Hess says that the greatest amount of interest for the budding technology has come from majors looking to boost ESG scores in their Middle East operations. There is some interest in the Permian, along with Canada and South America. Current economics for the Permian, with the short operating life common to shale wells, makes the $4 million investment a stopping point for most producers here.

How It Works

Gas-to-liquids (GTL) systems as a whole have been around for almost 100 years—they just haven’t been economically viable or scalable. German chemists Franz Fischer and Hans Tropsch developed the Fischer-Tropsch procedure in 1925. Hess says the new, patented ENG system uses a form of that older system, with some improvements.

Gas-to-liquids (GTL) systems as a whole have been around for almost 100 years—they just haven’t been economically viable or scalable. German chemists Franz Fischer and Hans Tropsch developed the Fischer-Tropsch procedure in 1925. Hess says the new, patented ENG system uses a form of that older system, with some improvements.

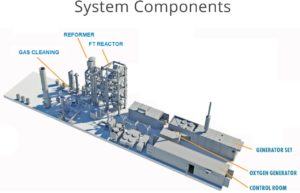

Its first major component is a small, energy-efficient gliding arc plasma reformer, which converts the wellhead gas and sends it to the second component, a modified Fischer-Tropsch reactor. Hess notes that the modifications give the operator precise control of temperature and flow, allowing the system to be more economical than previous Fischer-Tropsch models.

The only input involved is the gas, some of which powers the system, and water. No pre-treatment is necessary unless there is a presence of H2S, which must be removed. Hess says the company is developing an electric version to further reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

End Use

Producing diesel or naphtha would require onsite storage. But synthetic crude, which comes out as a relatively light AT43, is of interest to producers in both the Middle East and Canada. In those locations they would likely inject the synthetic crude into the pipeline to improve flow of those regions’ much heavier product.

Hess added that some countries import diesel, so they could use the process for synthetic diesel to be added to the refined product. “The highest dollar value is in naphtha—so, depending upon where you are and what your client base is, that may be a better alternative.”

Data Aggregation as a Sleep Aid

“When you think about what keeps most companies awake at night, which is creating efficiencies within their organizations for a rapid and ever-changing market environment they’re pursuing—[the issue is] how do I leverage data, data technology and capital investments more effectively than I ever have before?” said Datagration CEO Peter Bernard.

The company’s PetroVisor software is designed to put bleary-eyed executives’ concerns to rest by aggregating data from wellhead to accounting, making it useful for those departments and everyone in between.

Referring to their technology as a “unified data model,” Bernard explained that it “allows any disparate data source to be brought together into a database” that automates accessibility including financial, geological, operational, production, and all sectors of the company. “It allows companies to visualize it and make decisions more effectively, from the pumper in the field all the way to the C-level,” he continued.

Bernard says the extent of data aggregation is a groundbreaking achievement previously unavailable. To that point, in presenting PetroVisor to potential clients he is often first met with disbelief. At first, “Most people say that’s not possible, no one’s ever done it before,” he said.

Datagration’s first dozen or so clients who have signed up have quickly become convinced. The next level for those companies is internal—getting everyone up and down the spectrum to buy into the fact that all the data really is together under one click.

Upon installation of PetroVisor, the aggregation is done by the software itself, Bernard said, with little to no company involvement. It does that by copying the data from existing systems rather than by owning it, which gives the company greater data security. The initial process also often reveals and corrects faulty data among the disparate systems, allowing for correction.

Working in the Material World

So how does this play out in the real world? To analyze a particular well, PetroVisor collects and analyzes current and historical data and boils it down to what’s important. “There’s so much data coming in on that one [well] every day—we take it and boil it down to a simple way to view it. We run it through our algorithm, machine learning, and artificial intelligence.” When they do so, the system automatically spits out the information needed for decisions.

The data would show if a well went down, the condition of the pump, what repairs should be made, tand the cost for those repairs (from the previously separate accounting database) against the well’s productivity. It can rank all wells by productivity (how much money is it making), versus repair/replacements costs for recent similar wells, giving complete data for deciding next steps.

ESG Benefits

As wellhead emissions of greenhouse gases (GHG) come under increasing scrutiny by the EPA and other regulators, environmental groups, and investors, Datagration sees an opportunity in the environmental, societal and governance (ESG) realm.

As wellhead emissions of greenhouse gases (GHG) come under increasing scrutiny by the EPA and other regulators, environmental groups, and investors, Datagration sees an opportunity in the environmental, societal and governance (ESG) realm.

“Within the PetroVisor platform, we’re able to go back and look at every tank battery, compressor station, every piece of equipment that a company operates—we can pull that from their accounting system and we can give it an emissions profile associated with how much it burns, how much electricity it consumes, and tie that back into gas emissions,” Bernard said That lets the user build a more systematized system of detecting and stopping methane leaks, analyzing water usage and more, using the platform’s dashboards.

PetroVisor and its associated program, EcoVisor, also download all EPA flyover information about flares, leaks, and other issues, into the platform.

Next Steps

In 2025 Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) is likely to begin including ESG scores in financial reporting, so the impetus to forge ahead with software and procedures to boost those numbers is growing daily. And herein lies the rub, Bernard observed. Even in light of pandemic disruptions and reporting changes, “We’re still slow to adopt technology” in the oil and gas industry. “As an industry we’re comfortable doing what we do in a repeatable process in our own silo.” He adds that higher oil prices have lulled some companies into believing that they don’t need to become more efficient through technology.

When oil was at $35 per barrel during the pandemic there was urgency, but in that situation producers were bleeding red ink and couldn’t afford oil changes in company vehicles, let alone an investment in new technology. “I’ve dealt with it my whole career,” Bernard said of the cycles, covering a span of 38 years.

More companies are indeed adding data capture, but with billions of datapoints assaulting most companies every day, most are still lagging in the interpretation and use of that information, he said. There is somewhat of a divide between younger generation employees eager to use a smart device vs. upper management that is often still set on older systems, Bernard believes.

One change the pandemic did force on everyone, he noted, was remote working. No longer could someone walk over to accounting for a spreadsheet printout. Suddenly everything was electronic, especially meetings. Cloud-based technology was part of that.

“At the end of the day,” he concluded, “the industry broadly has gotten focused on cash flow. I think understanding how to leverage global demand, that we can create in the Permian Basin and apply, technology is a critical part. I think its going to force us to go in that direction.” But it still requires vision to move forward.

Finally, “Those that adopt technology are the ones that are going to be around, and those that don’t, won’t.”

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Paul Wiseman is a freelance energy writer. His email address is fittoprint414@gmail.com.

Producing oil and gas wells have one thing in common…..they all produce saltwater that must be

disposed of according to the RailRoad Commission.

That costs money.

Why not turn that produced water into fuels and make

disposing of produced saltwater a thing of the past, not a liability of production overhead?

I have a modularized system to do just that, make produced water a profitable fuel.