Colin P. Fenton is a leading light among an emerging coterie of thinkers who are not drinking the anti-fossil fuel koolaid. His thoughts shared before the PBPA give hope for a reversal of public opinion, however far away that might be.

A few days after Colin P. Fenton delivered a resounding keynote address at the Permian Basin Petroleum Association’s annual meeting, he was fielding questions from Permian Basin Oil and Gas Magazine about his talk and about the reception he received in Midland. Among those questions was an inquiry as to how an audience of Permian Basin oil and gas professionals presumably differ from an audience he might typically face somewhere else

His reply:

“It’s easy to speak with the members of the PBPA. They know the oil and gas industry cold. They are also among the warmest, kindest, most humorous, most inquisitive, and most ethical human beings I’ve ever had the pleasure to meet in a quarter-century of travels to the far corners of the world. In some venues, my audiences may be antagonistic toward hydrocarbon production and use. But to be fair, my experience has been that if the research is thoughtfully-framed, based in fact, and presented calmly, logically, and honestly, anyone’s mind is open to instruction and change.

“For example, I gave the keynote speech at the 2017 Sustainability Conference of The Conference Board. That audience included more than 75 Chief Sustainability Officers (CSOs) drawn from the S&P 500. Many had vested professional incentives to avoid or reject oil and gas focused research content. But after my remarks, many approached me in the hallway to ask questions, share business cards, and inquire about getting more access to my research.”

Such a reply is characteristic of Fenton, a witty, articulate, well-versed analyst whose independent research into oil and gas realities has led him away from the party-line politics and even “propaganda” (Fenton’s word, and others’ too) pushed by today’s green lobby in its war on fossil fuels. Fenton’s address to the PBPA was, in fact, titled “Hydrocarbons Boom in the Age of Folly and Hammers,” a play on the idea of Soviet propaganda from the early-mid 20th Century. (See accompanying image.) His refreshing rebuttals of much of what gets fed to a largely unquestioning public sparked hopes that someday, perhaps, the tide will turn and fossil fuels will come into their own in the public eye.

Comparing his October visit to the Basin with the visit he made here three years prior, just as the downturn was beginning, Fenton told members of the PBPA: “I have to admit, it takes my breath away to see how successful you have all been… I did not anticipate that we would have the Permian now producing 3.5 million barrels per day.”

Fenton:“The members of the PBPA know the oil and gas industry cold.” Healso remarked that PBPA members “are among the warmest, kindest, most humorous, most inquisitive, and most ethical human beings [he’s] ever had the pleasure to meet in a quarter-century of travels to the far corners of the world.”

Remarking on Fenton and his talk in October, PBPA President Ben Shepperd had this to say: “The PBPA has always worked to share the most accurate and factual information available to our membership to help them make informed decisions. Much of that work is in the legal, legislative, and regulatory arenas, but economics drives it all. We are fortunate to have someone as knowledgeable as Colin who is willing to share his insights with us to help us better understand the constantly changing economic dynamics of our industry.”

Constantly changing. That is indeed descriptive of the attacks leveled at oil and gas in these tumultuous times. Fenton told PBOG that the propaganda spewing from legal and policy circles has suffocated the public’s hearts and minds. As is typical of propaganda, there is a chameleon quality to it—with the party line changing as false claims are defeated and hidden agendas are exposed.

Much of the attack leveled against oil and gas is packaged as “science,” but Fenton is not buying what they’re selling.

“It’s bilge masquerading as science,” Fenton said. “I have been stupefied by the speed with which vacuous concepts such as ‘fossil free,’ ‘carbon bubble,’ and ‘stranded assets’ have been created, sold, and accepted as dogma. All this has happened in the salons of Manhattan, San Francisco, and Cambridge within just the past five years, thanks to deep pockets of political and financial backing. That such demonstrably flawed postulations have passed unchallenged as incontrovertible fate proves the public is not paying sufficient attention. It’s disheartening to anyone who grasps the big picture and the creative problem-solving powers of technology and the capital markets. Worse, some of the promoters of these trendy views—when sufficiently badgered by a research analyst in a private setting—will make light of the chicanery afoot with the excuse ‘it’s just politics.’ ”

The good news, though, is that inevitably the oil and gas industry eventually will be understood in a different light. That light is called ‘science.’”

Real science, not concocted or imagined “science.”

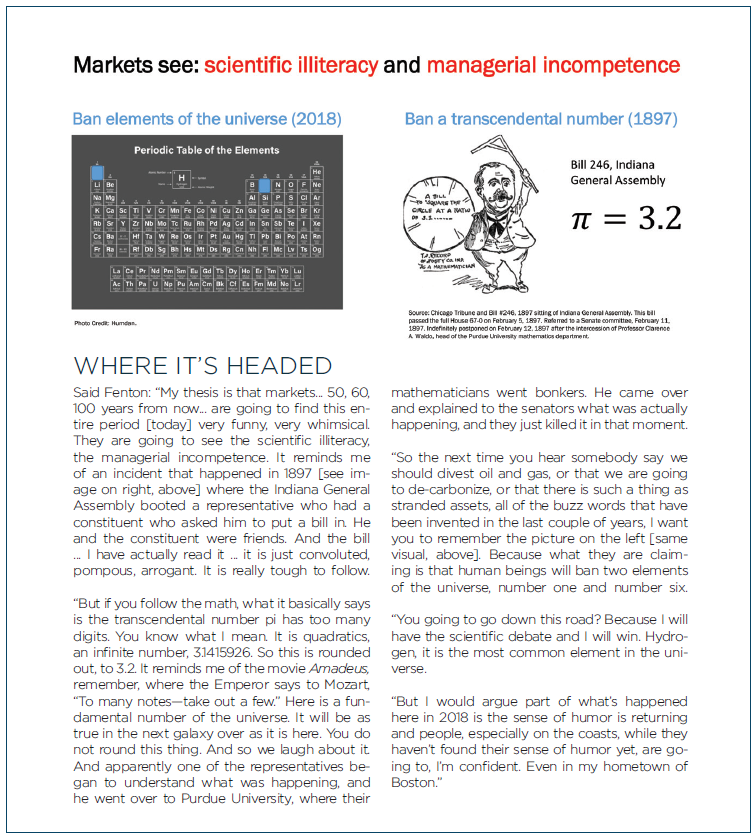

The “folly” of Fenton’s title is seen in that “bilge” that he mentions. When he opened his talk in Midland, he cited his “folly and a hammer” theme for his talk.

What are follies? They are “political posturing, investment policy confusion, and regulatory mistakes,” among other things. What are hammers? Hammers are “fierce corrections wielded by the invisible hand, the market hand, and the regulatory hand,” among other forces. (See chart for more.)

“I’m going to argue that one way to look at oil and gas and all of the derivative products is to understand that our civilization is wrestling with many follies—ideas that may be partly out of touch with reality or severely out of touch with reality,” he said. These ideas are pushed upon the public, and they are directed most pointedly at the public that resists the message. The party line is wielded as a way of “punishing” the unconverted.

“They punish you when you get too ‘arrogant,’ too ‘dogmatic,’ when you don’t listen to the world,” Fenton said.

And much of this punishment is leveled in the name of science. But the irony, as Fenton keeps pointing out, is that the science and the “research” directed against the green lobby’s targets is sadly lacking in substance—and in many cases is mere made-up allegations.

“If you start claiming the mantel of science, but you don’t actually pay attention to material science, you’re not talking about science,” he said.

Besides science, there is the even more mundane world of just everyday fact. And everyday facts get lost, apparently, in these days when political objectives trump realities.

Fenton offered a fact that is too-little noticed:

Electric cars are fabricated from gas-based feedstocks and other hydrocarbons.

He counterpointed that “demand” fact with a “supply” fact. The fact that deep lakes of liquid methane (LNG) dot the surface of one of Saturn’s moons, Titan. He offered an actual photo of the lakes as proof. And his point was this: are we to believe that there were once dinosaurs roaming Titan? If not, what does that say about the potential sources of hydrocarbons in the universe, and even just here on earth?

Why this existence of hydrocarbons on Titan matters is because the propaganda that is spread by oil’s naysayers is that oil and gas come exclusively from “dinosaur remains,” and when that very-finite fossil source is exhausted, so is all oil and gas activity, and so is all oil and gas productivity—and the energy derived from it. The “dinosaur” motif, propagated by oil itself when Sinclair trotted out its “Dino the Dinosaur” symbol in the early 20th century, has not been good to oil and has become a weapon used against it by oil’s enemies.

But there are more hydrocarbons in the ground than could ever have been the result of decomposition of dinosaur remains. And there is more to hydrocarbons than just energy—just fuel. There is a world of products created from hydrocarbons, and without those products, we’d live impoverished lives, thrown back to civilizations utilizing mainly “leather and wood,” as Fenton put it, for most of our implements and products.

“Without hydrocarbons, Tesla’s sedan, and Tesla as a company, ‘blink into nonexistence, in a poof of irony,’” Fenton said, employing one of his patented Fentonisms. “They’re gone. The chassis is made of thermal plastics. The tires—synthetic rubber. There are adhesives and other products throughout the vehicle. And don’t mis-hear me. I am not attacking electric vehicles. I can show you that there is a place for electric vehicles and natural gas vehicles and fuel cell vehicles, and it would be a folly to just throw up your arms and say I don’t need to worry about [or can’t use] those.”

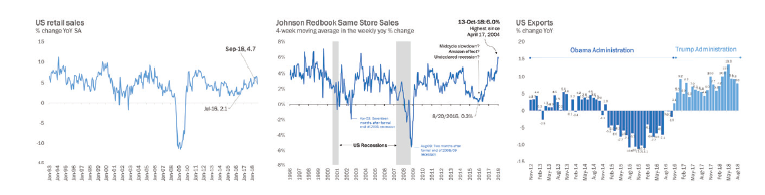

What these charts have in common (as is explained in the text) is a dip in 2016 that may have been indicative of a recession that economists failed to identify.

Fenton had much more to say about current conditions in his nearly-hour-long talk that seemed 15 minutes long. And while we must pass over his remarks about the markets, about the Paris Accord, about the periodic chart, about emerging world demand and other topics, we have space for just this remaining discussion of the economic cycle.

Fenton posited that maybe, just maybe, the United States experienced a recession, even if only an “invisible” recession, and about two years ago, and if he is right about that, then much of the handwringing in the current market about an impending recession is misplaced.

“It’s true that the yield curve of the United States has begun to get to scary levels that have preceded recessions,” Fenton allowed, “but it’s actually been bouncing back since late August. I’m going to give you a contrarian idea here. Most of my peers in markets would tell you that a U.S. recession is highly likely within the next 18 months. Most people really believe that we’re late in the cycle, and we’re due for a recession.

“[But] those are the actual industrial production statistics of the United States,” he said, referencing the statistics shown in the chart reproduced on this spread [see figure tktktktk]. “They actually already contracted in ’15 and ’16, so it is not arguable that the United States had a manufacturing recession already, several years ago. In fact, I went on Bloomberg TV, and I said I could view the United States [then] as being in a recession, and the host nearly fell out of her chair. She was like, ‘That’s a ridiculous thing to say. How could you be a professional forecaster, and say that?’ And yet, I repeated it in my research on September 24th this year. Five days later, the New York Times took that idea and published it. So what’s my point? My point is, a lot of the forecasters are beginning to say, “If I look at statistics… ”

He looks at statistics with us, pointing to the trend shown in the graph at lower right [same figure]. “Bottom right, trade already collapsed,” he said. “Those are the exports of the United States, and in the late second term of Mr. Obama’s administration, they actually contracted for many, many months, and they’ve been positive in the Trump administration. Those are just facts. Is that a recession? What do we call that? On the middle, bottom panel, those are retail sales. If it were not for Amazon, the U.S. would have had negative GDP in the first quarter of 2016. One company’s 30 percent growth rate in retail sales saved the entire U.S. GDP.

“So, I continue to hold to the idea that the next recession is maybe four to six years away, and so you may be about to see a boom,” he said, introducing a brighter note. “If you thought last year was a boom, wait until you see what happens over the next few years if that [conclusion] there is correct, because we’re going to have something like one and a half to 1.7 billion cubic feet of coal demand growth. U.S. petroleum exports have already doubled since the start of the downturn are going to continue to gather apace.”

And finally, this:

“The crude spreads that had been problematic for you, may still be problematic, but I think will get resolved with capital expenditure. As for pre-refinery utilization, before 2017, it was above 95 percent only 8 percent of the time. Today, that’s a third of the time. I can use some clever math to try to guess what your pipelines’ utilization rates are? Punchline is 99 percent, and that’s why you’re seeing the differentials that you’re seeing.

“And [that’s why] when I look at [the question of] why is everybody so worried right now—it literally looks to me like a circular firing squad.” [laughter]