Military training often translates well into oilfield occupations

By Paul Wiseman

“Words cannot describe—a great feeling, it had been so long.” These are the words of Jeremiah Penley, expressing his reaction to getting an oil industry job after a seemingly hopeless two-year search. Penley, a six-year Marine who saw action in Iraq and Africa, did odd jobs while tracking down every employment lead he could find after he mustered out in 2012. At times, he said, he wondered if he would ever find work.

With his training and experience, his struggles surprised him. “Not only was I a veteran, I have a college degree. You would think, with a college degree and being a veteran, it would be easier to get a job,” he reflected.

The job that brought Penley to tears seems pretty basic—he’s a land tech for a Birmingham, Ala., E&P firm with holdings that include the Permian Basin—but to him it means he can comfortably support his family without having to travel for weeks at a time. And, while the job is mentally demanding, he does not have to worry about enemy fire, being reasonably assured of coming home safely every night.

How he got the job is a story in itself, involving a company called Vetergy, which was started by another former Marine, David Wilbur, who also lives in Birmingham. The two men’s wives met at the beauty salon where they share a hair stylist.

Vetergy’s mission is to qualify and train veterans for oilfield jobs, then help connect them with potential employers. Some hiring is done directly through Vetergy and other hiring is done on an individual basis. Wilbur said the concept has been well received in the industry through its first year-plus of operation. He reports a placement rate of better than 100 percent.

Here’s how he figures that percentage: “One company wanted to hire three veterans, so we sent them five people to choose from,” he said. “They looked at their qualifications and gave all five of them jobs. They created two new positions in order to do that.”

The veterans they place typically do very well, he said, citing Penley in particular. Wilbur had lunch with Penley’s employers after the hire and, as he recalled, “It becomes almost embarrassing the way they talk about how much they love this guy. That’s the stuff that gets you out of bed in the morning.”

When a veteran comes to Vetergy, the company begins by evaluating the veteran’s military skillset, known in the service as Military Occupation Specialty, to see if and how it would translate to an oilfield job. After that, Vetergy offers, through a third party, a long list of online classes that provide overviews of various aspects of the oil industry. Then they either directly place the individual or give him or her some information on how to apply and who might be looking to hire veterans. They currently have 200 names on file, representing veterans who have completed the process or are currently enrolled.

Regarding job appropriateness, for example, a motor equipment operator in the military has skills that will easily translate into driving a truck in the oilfield, with a little additional training on the specific equipment on the truck. That falls into the category of a “hard skill.” On the other hand, what Wilbur called “soft skills” include leadership, organization, management, discipline, and other organizational abilities.

Being a total team player is one of the core values ingrained in military training, which is another soft skill that translates well in the oil patch. The challenge here may be that a deployed soldier is surrounded by people with similar training, who all understand the necessity to watch each other’s back—while on the rig there will be those who don’t have the same understanding.

Often, the veteran can lead by example, Wilbur said, helping everyone to work more as a team.

One might think that an oilfield job is less dangerous than a battle zone, but that’s only partly true, said Wilbur. “Nobody’s shooting at you, but the threat scenario is identical” due to the dangers of being injured by heavy equipment, poisonous gases, and other occupational hazards. “The pressures you’re dealing with on the equipment, it wants to kill them just like an enemy does, and [veterans] have a healthy respect for it.”

Wilbur noted that the environment in military deployment is very similar to that of a well site, from the presence of heavy equipment to the aroma of hydrocarbons in the air, along with dirt, sweat, and, occasionally, blood, making the veterans feel right at home.

Taking orders and executing them to exacting standards is another soft skill that translates well overall. However, instructions in the oil patch may not always be as clear as they need to be, which can create challenges for veterans who come from the lower ranks, where they were never required to do anything but follow orders. Those who ascended to become middle ranked officers tend to do the best of all workers. “E6 to E8 is the sweet spot,” both age-wise and training-wise, Wilbur said. E6 is a Staff Sergeant and E8 is a Master Sergeant.

Sometimes the biggest challenge of all is getting employers to understand how well the military skillsets translate into oilfield qualifications—a task at which Wilbur said he has had good success.

Wilbur himself spent time as a performance excellence coach in the oil fields of the North Slope of Alaska, putting his military training to use there in improving performance and efficiency. He was in the Marine Corps for 20 years, serving in Afghanistan and Iraq, among other places, fulfilling distinct roles as the Director of Safety and Standardization, Director of Operations, Chief of Staff / Executive Officer, and Chief Executive Officer / Commanding Officer during his time. After seeing how his military training could be used to train workers in Alaska, he decided to form Vetergy to help other veterans get high paying jobs in the industry.

Another Marine, Jerry Fuentes, points out that this branch of the service is often asked to “do more with less. We’re the smallest branch of the service—and we’re taught that we have less, but we’re required to do more,” so efficiency training is of the utmost. Fuentes, in the service from 1996-2009, retired due to a combat injury and founded Veterans Fabrication in Midland the year he left the service. He began as an enlisted man and became an NCO (Non-Commissioned Officer) before he had to retire.

His company began as a robotic welding firm—he notes that they are the only company with ASME Code certified robotic welding machines in the area. Now it has four of those machines and has expanded into vapor recovery, instrument air systems, glycol dehydration and other areas, with several patents.

Fuentes said his military training taught him leadership skills in general and forward thinking in particular. “When we see change coming, we try to be proactive,” he said. He cited his company’s readiness to sell products that meet new EPA “Quad 0” standards before they are mandated as an example of his forward thinking.

Leadership is also about team building. “I want to empower my employees to make certain decisions in order to help them grow as individuals. This is a small unit [six employees],” so everyone knows everyone else very well. It may not be an accident that he uses a military term (unit) to describe his team of employees.

“I can be a Type A personality, but I know that and I try not to be a micro-manager. I’ve heard it said that good leaders are born, but great leaders are made. I want to nurture people in order to help build the company.” He also takes into account that each person has a different learning style when training or motivating team members.

Fuentes made the investment in robotic welding from the start because he saw that the larger upfront investment would pay off. When properly programmed, robotic welders can weld large numbers of items more accurately and many times faster than humans can, which means he can charge less than non-robotic shops and still earn a profit.

He cited a recent job that involved cutting precise holes in 75 tanks. Not only did the robots do the job in very short time, the machines do not get bored or distracted when doing repetitive tasks.

“Lots of people told me I was crazy [to buy robotic welders] but I knew the investment would pay dividends,” he recalled. “Now I’m able to bid 20-30 percent under the others. When clients ask me ‘How do you do that?’ I say, ‘Let me show you.’”

Fuentes further keeps costs in line by doing all programming and repairs of the robots in-house, which also reduces turnaround time for preparation and down time for repairs. In the downturn this has really paid dividends as more companies have switched their business to Veterans Fabrication. He sees this as a family benefit.

“As the business owner, I have a responsibility to both my own family and those of my employees. Every decision that is made extends way beyond me—all the way down to my foreman’s son.” So decisions that allow them to keep costs low and keep everyone working even in slow times pay dividends on many levels for Fuentes.

His military training also helps him build trust among current and potential clients. “They learn who we are over time, and learn to trust us. We’re not just some guy with a welding machine in his backyard. They get to know us and our organization and trust that we can build things to accepted standards… we have the certifications, insurance, and OSHA records,” he said. Giving tours of the shop helps—and Fuentes is not afraid that a competitor will copy him.

“You can’t just jump in—it’s challenging to learn all that’s needed to make this work right.” He said he knows of others who have bought robotic welders, a great expense, but who never got the training to operate them properly, so the investment was wasted.

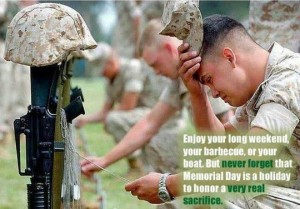

If, somewhere, there is a collection of overused phrases, “win-win situation” would be near the top. But when it comes to matching military training with oilfield needs, that is exactly what the situation has proven to be. Companies get dependable workers and veterans like Jeremiah Penley get good jobs that help them remain proud of their military service. And that is something to think about during May’s Memorial Day celebrations.

Paul Wiseman is a freelance writer living in Midland, Texas.