Drilling a well in any oil formation actually produces three things: Oil, natural gas (and associated liquids), and water. All of it must go somewhere on its way to processing, disposal, or reuse. As those ratios change, apportioning the midstream capacity can be a moving target, especially when those investment decisions and construction windows involve five years or more.

The Pandemic also rocked the planning boat, as production of all three shriveled—for a while—only to roar back to all-time record highs since late 2021. And the gas-to-oil ratio (GOR) continues to rise as Permian wells drilled in the last decade continue to mature. And the old plan of simply flaring excess gas is no longer deemed proper, for both economic and environmental reasons. What’s a planner to do?

Right now, says Suzie Boyd, founder and president of midstream consultant firm Caballo Loco, oil pipelines are ahead of the game on spare capacity, due to a large buildout leading up to 2020. “Crude pipelines currently have ample capacity but we will see these fill up over the next few years,” she said in an email interview.

But gas pipelines are already stretched, with help on the way but not yet in service. Rising GORs are part of the issue. Boyd said, “Production in the Delaware Basin is particularly gassy with GORs in excess of 3,000, meaning for every one barrel of oil, there are three or more Mcf [of natural gas] produced.”

Because of those high rates, she says there is little spare processing capacity (necessary before sending gas into the pipeline) in that basin, especially across the New Mexico border. But help is on the way. “There are at least 10 plants under construction in the Delaware by the larger midstream players, including Enterprise, Targa, Western, and Energy Transfer,” she said. “In the Midland Basin, there is a similar story. Processing capacity is very tight with at least seven plants under construction by WTG, Targa, and Enterprise. With a construction time of over a year, these plants are coming online late this year and next.”

Since 2021, the President has leaned on the oil industry to drill and produce more. But those overtures have been met with pushback from producers leery of large investments that may become obsolete, in the energy transition, before they can pay out. It’s much the same in the midstream sector, says Boyd.

“Large projects require underwriting for at least 10 years in order for the investment to earn an acceptable rate of return. The regulatory and permitting environment is a challenge, as protesters have developed creative ways to interfere with development, especially pipelines.”

While not directly affecting the Permian Basin, the Keystone XL pipeline extension from Canada to the United States was probably the poster child for challenges. Proposed under Bush in 2008, canceled under Obama, reinstated under Trump, and re-canceled on Biden’s first day in office, it bounced around like a basketball in a dribbling contest.

While the Permian Basin has faced fewer challenges, likely due to its relative isolation and its high percentage of residents who earn their living from oil and gas, other areas of Texas are seeing pushback.

In 2019, an Austin court dismissed claims filed against the construction of the 430-mile Permian Highway Pipeline (PHP) designed to carry natural gas from the Waha hub in West Texas to Katy, Texas. Owned by a group including Kinder Morgan Texas Pipeline LLC, Eagle Claw Midsteam, and Altus Midstream, the line went into service in 2021, providing approximately 2.1 billion cubic feet per day of incremental natural gas capacity.

Since then Kinder Morgan has announced its intention to boost the line’s capacity by 550 MMcf/d. The company’s website says, “The project will involve primarily additional compression on PHP to increase natural gas deliveries from the Waha area to multiple mainline connections, Katy, Texas, and various U.S. Gulf Coast markets. Pending the timely receipt of required approvals, the target in-service date for the project is anticipated to be November 1, 2023.”

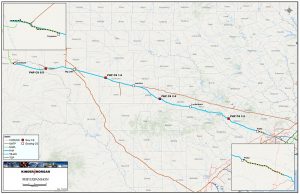

This map shows the route of the Matternorn Express Pipeline. This 580-mile intrastate pipeline is designed to transport up to 2.5 billion cubic feet per day of natural gas from the Permian Basin to the Katy area near Houston, Texas.

The transport of natural gas has received greater attention from planners as the supply of natural gas coming out of the Permian has burgeoned in recent years.

Another pipeline victory, this in Virginia, came about in March when a federal appeals court said regulators in that state had indeed thoroughly reviewed the Mountain Valley Pipeline’s environmental impacts in okaying the project. A lawsuit filed by the Sierra Club had alleged to the contrary—one of several suits over the course of its construction, which as of March 29 was estimated by its owner, Equitrans, at 94 percent complete. This ruling was expected to be among the last hurdles for the pipeline, which will carry natural gas between West Virginia and Virginia.

Sanctions on Russian oil and gas due to their invasion of Ukraine have created new needs for exporting Permian natural gas in the form of liquefied natural gas (LNG). Much of that LNG goes to Europe, but the Far East is also a substantial customer. With exports increasing, Boyd says that means, “…most new pipeline construction is pointed toward the Gulf Coast. The existing outbound gas pipelines from the Permian are running at or near capacity.”

That “at or near capacity” phrase is loaded with meaning, says Boyd. So, “any time there is a pipeline out for maintenance, there will be gas that gets backed out or required to go into distress pricing to get it moved. We are likely to see some negative Waha prices over the summer.”

New pipelines are on the way, including the PHP expansion, but Boyd sees that capacity quickly being soaked up at the rate production is growing. In late 2022, S&P Global Commodity Insights made similar predictions. Their report said, “The Permian Basin natural gas market is likely to see another midstream capacity crunch in 2023 as growing output there would put existing production takeaway pipelines to the test and keep hub prices in West Texas under pressure.

It continued, “Gas production from the Permian has continued its upward march in 2022, rising about 1 Bcf/d over the past 12 months, raising alarm among market participants over the basin’s capacity to handle additional growth in the year ahead. As of December, production is trending around 15.8 Bcf/d, with daily output continuing to test new record highs at over 16 Bcf/d—not far from the basin’s theoretical maximum of around 17-18 Bcf/d, data from S&P Global Commodity Insights shows.”

The report went on to note that the rate of gas production increase had slowed in the latter part of the year, due to concerns about rising drilling costs and supply chain shortages affecting everything from availability of drilling equipment to staffing. That’s given some producers pause as they think of boosting production.

But S&P still expects production to outstrip takeaway capacity by Q4.

Other new lines on the list include the Matterhorn Express pipeline, “a Joint Venture with WhiteWater, EnLink Midstream, Devon Energy, and MPLX. Matterhorn Express is an approximately 490-mile, 42-inch intrastate pipeline designed to transport up to 2.5 billion cubic feet per day [Bcf/d] of natural gas from the Permian Basin, to the Katy area near Houston, Texas,” according to White Water’s website. Boyd says its expected in-service date is in Q4 of 2024.

Processing Must Also Keep Up

Natural gas must be processed and cleansed of many impurities before being allowed access to pipelines. So processing plant construction must also keep up. Fortunately, plants cover only a few acres, so their construction and planning lead time requirements are much less than those of midstream.

The Permian Highway Pipeline, LLC (PHP) expansion project will increase PHP’s capacity by approximately 550 MMcf/d. The target date for completion is Nov. 1, 2023.

S&P notes that growth in this sector is on its way. “Over the past six months, U.S. midstream players, including Targa Resources, Energy Transfer, Enterprise Products Partners, and MPLX, have announced plans to add at least 700 MMcf/d of processing capacity to the Permian Basin by 2024.”

One example of this growth comes from Targa, which plans to relocate an Eagle Ford processing plant to the Delaware Basin. They are also moving forward with construction of four other plants in the Permian overall. The Houston-based midstream heavyweight says those projects will add 1.2 bdfd of processing to its Permian operations.

And while many in the ESG community are pushing for repurposing natural gas pipelines for use in transporting hydrogen, or in moving captured CO2 into underground sequestration facilities such as those proposed by Oxy near Odessa, Suzy Boyd points out that there are not any natural gas pipelines in the Permian that will be empty any time soon.

By Paul Wiseman