Sometimes at the convergence of two problems there is a solution. The fact that Permian oil wells are getting gassier (setting new production records regularly) and straining gas takeaway capacity is one—and issues with massive grid demands of bitcoin mining and data processing is the other.

Increasingly, producers are seeking alternative markets for gas, and one of those involves direct supply of gas for onsite power to datacenters and cryptominers, users that would otherwise strain the electrical grid.

Power-Hungry Cryptocurrency/Data Center Computing

Cryptocurrency mining in the United States uses somewhere between 0.6 percent and 2.3 percent of the nation’s electricity, according to estimates by the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) and others. Worldwide, bitcoin miners use about 6 percent of the world’s electricity, the same amount as is used by the Netherlands every day, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA).

For a single miner to mine one bitcoin it would require 266,000 kWh over 7 years, according to Coingecko. Divided out per month, mining one bitcoin would take about one-sixth the electricity consumed by one U.S. home per month. Another crypto site, Bitbo, estimates that there are 1 million miners worldwide. That would mean that mining uses approximately the same power as around 167,000 homes.

Add data centers to the mix, and computing power demand rises to about 6 percent of the U.S. grid, which is already increasingly taxed by population growth and the rise of electric vehicle (EV) charging stations.

A few years ago, some enterprising bitcoin miners recognized an alternative to overly straining the grid to get their power. Observing that the oil and gas industry, particularly in the Permian Basin, was flaring enough gas every day to generate power for the entire state of Texas, it seemed natural to tap into that otherwise wasted resource. They would get power at wholesale prices, it would not be subject to grid outages, and by reducing flaring it would check off ESG boxes.

A “True Symbiotic Relationship”

“The combination of bitcoin and natural gas is one of the very few true symbiotic relationships there are,” said Opportune’s Commodity Risk Advisor Ryan Dusek. “The producers have an outlet for the excess gas they can’t flare, and the bitcoin miners are happy to take it.”

Typically, miners haul a container-sized setup with computers and cooling equipment to the well site, along with a gas-fired generator. The generator connects to the gas line and the mining computers hook up to the generator. Because of that, there are no transmission costs—neither gas nor electricity travels more than a few feet. That means miners get a better price for their power, and oil producers sell natural gas that would otherwise just be flared.

Dusek added that the Permian Basin is uniquely suited to this bargain for two reasons: Its remoteness and the fact that natural gas is a byproduct, so its production can’t easily be notched down if supplies exceed takeaway capacity.

Remoteness matters because gathering systems must run for miles to approach a main pipeline, so even if there is capacity in the trunk system, it can take weeks to connect. In the meantime, produced gas must be flared, and flaring has the double whammy of being unprofitable and bad for ESG scores. Yet, he added, the Basin is not so remote that computer equipment can’t be hauled in—after all, drilling equipment is delivered all over the Basin.

On the second point, natural gas prices went negative at the area’s Henry Hub more than once in 2024. If, on the other hand, a producer is selling directly to a cryptominer, the price for buyer and seller will be constant, rain or shine, for the life of the agreement.

For that reason, Dusek said it would be wise for producers to initiate the call. “Anywhere that infrastructure is rare, that’s the best place to bring in these guys. It seems to be growing in Texas.”

In fact, Dusek said half of all bitcoin mining in the United States is in Texas. A distant second, at 20 percent, is New York, where miners connect to clean hydropower.

Why Texas in particular for bitcoin miners? Riley Prescott, analyst at Enverus Intelligence Research (EIR), says there’s been a migration here from China since 2021. “One of the things that’s appealing for bitcoin miners in West Texas is… you have oil and gas production, but you also have low-margin, low-cost renewable power generation. So, generally speaking, in the West Zone of ERCOT you’re seeing lower prices on average, at least historically. That’s very attractive to the bitcoin miners. That and the state’s more ‘open-for-business’ policies.”

Saving the Grid

Dusek pointed out that any cryptominer who’s drawing gas from the wellhead is also not adding load to an already taxed electrical grid in Texas. This is especially critical in the summer air conditioning season, when demand is at its highest level of the year.

And beating back the Texas summers, cooling those bitcoin mining computers, is a significant part of their power requirements. Overheated systems slow down, become less efficient, or shut off completely. Bitcoin mining is essentially a competition to see who can solve for a coin first (see below for an explanation), so speed is important—and a cool computer is a fast computer.

Dusek pointed out that there are indeed a significant number of bitcoin miners on the grid, and the state’s population is exploding, so demand is growing exponentially. Because of those factors, grid manager ERCOT is warning that the system could be facing brownouts, especially if the increasing reliance on wind were to fail on a hot, calm day. In short, “The more renewables you have, the more uncertain your supply becomes.”

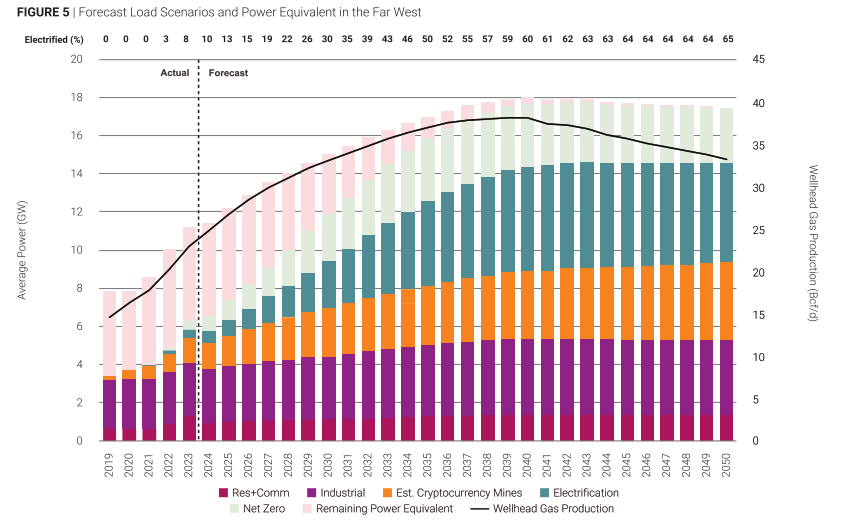

While ERCOT has predicted the state will need another 20 GWH of grid capacity by 2030, EIR sees the situation as less dire—but still short by about 9-1/2 GWH, Prescott said.

“We really view ours as a realistic case, out of all the different contributing load factors, from population to electrification of oil and gas, crypto currency mining growth, all the relevant factors.

“We have a forecast where we lay out what we’re expecting to electrify. We’ve primarily focused on stationary sites with long expected lives, primarily on the compression side of things like onshore production, gas gathering, and processing piece,” Prescott said.

With grid challenges in the vast expanses of the Western District, oil and gas production itself puts a strain on the grid. In light of that, operators are turning more to produced gas to power their pumps and onsite equipment.

Another tactic, especially for Big Tech companies, is to identify underutilized gas-fired generating plants, and locate near them. Said Prescott, “They’re really looking to get reliable power generation where they can get it, that being the main factor, the reliable generation piece.”

Rising demand is half the equation—and adding generation capacity/transmission lines is the other.

It’s Not Just the Permian

In the Permian, gas is almost classified as a nuisance that must be handled in order to keep the oil flowing. In Appalachian basins of West Virginia, gas is the only thing, says Ganesh Sakshi, CFO of Mountain V Oil and Gas, so producers there have different

motivations for expanding their options. While there’s been no lack of takeaway capacity to push cryptocurrency connections, commodity pricing has been an issue. “The problem that producers in the Northeast try to address is the basis differential between where the NYMEX is trading versus where Appalachian gas is sold,” he said.

He continued, “It typically rotates around the cost of transportation, so 80 cents to a dollar (per MCF) behind NYMEX is the difference, and producers here have accepted that.” Accordingly, they plug the smaller number into their profitability calculations before starting a project.

But if they can get more by selling directly to cryptominers, that’s a bonus. Sakshi sees this as more an option for smaller operators like Mountain V than for the big ones. And even with midstream availability, some remote mountain areas are difficult and costly to connect with pipelines, so selling to cryptominers can boost profits, he said.

The option of turning natural gas into off-grid power for individual clients has risen since the first of 2024 because it’s more and more seen as an enhancement to selling into the market. And clients are starting to line up at the state line. “This is not a build-it-and-they-will-come issue,” he acknowledged. “They’re coming to you, so you have to build it.”

Even so, there is room to grow. “There are a lot of them, but not nearly to the extent there are in the Permian,” Sakshi observed.

He added that operators and end-users alike realize that power companies are having a hard time keeping up with datacenter power demands, and utilities are certainly not going to stretch wires into the remote mountains in West Virginia for a single client.

What IS Bitcoin Mining…

Bitcoin and cryptocurrency are household words these days, but it’s safe to say that few people really understand the complex mechanisms behind creating value in those systems. While an entire article (or book, even) could be given to the subject, here’s how Investopedia defines it:

“Bitcoin is a digital currency that requires a process called mining. Bitcoin mining is a network-wide competition to generate a cryptographic solution that matches specific criteria. When a correct solution is reached, a reward in the form of bitcoin and fees for the work done is given to the miner(s) who reached the solution first.”

…And Why Are a Million People Honing Their Electronic Pickaxes?

Again, we cite Investopedia:

“This reward process continues until 21 million bitcoins are circulating. Once that number is reached, the Bitcoin reward is expected to cease, and Bitcoin miners will be rewarded through fees paid for the work done.”

So someday this will come to an end—somewhere between seven and 21 years are the current estimates. Meanwhile, there’s gold in them there “mines.” But, Dusek said, if bitcoin prices drop as they did during the Pandemic, and it becomes unprofitable to burn the power to mine them, this could stop sooner than projected, at least until the price should return to profitable levels.

Other Gas Market Alternatives

Datacenter supply is not the only non-midstream option. Vertical producers are experimenting with retailing compressed natural gas (CNG) for local-market trucking, as Chevron announced in February for the Midland market. And, Sakshi noted, selling directly to the hydrogen-cracking industry is a growing option as well. He cited one project in Pennsylvania whose ultimate goal is to make hydrogen to fuel aircraft.

Classical Gas

While the market for natural gas through classic channels is not likely to end, especially as new LNG export plants come online in the next five years, a significant side market is forming. Whether that creates supply issues in the future will be an interesting situation to watch.

Paul Wiseman is a freelance writer in the oil and gas industry.