In 2020, oil and gas has gotten a bum rap.

Even in an industry that has almost always had to buck an unfairly negative sentiment from media and from certain special interests, oil and gas has taken a beating in 2020. In the past year or more, the financial markets have added their voices to the

outcry. Yes, profits are all but nonexistent in these depressed times. But Wall Street, in sniping at O&G, is ignoring certain factors that must be weighed in this controversy.

Here’s what the International Energy Agency had to say in their Flagship Report for the month of May:

“The speed and scale of the fall in energy investment activity in the first half of 2020 is without precedent. Many companies reined in spending. Project workers have been confined to their homes. Planned investments have been delayed, deferred, or shelved. And supply chains have been interrupted.

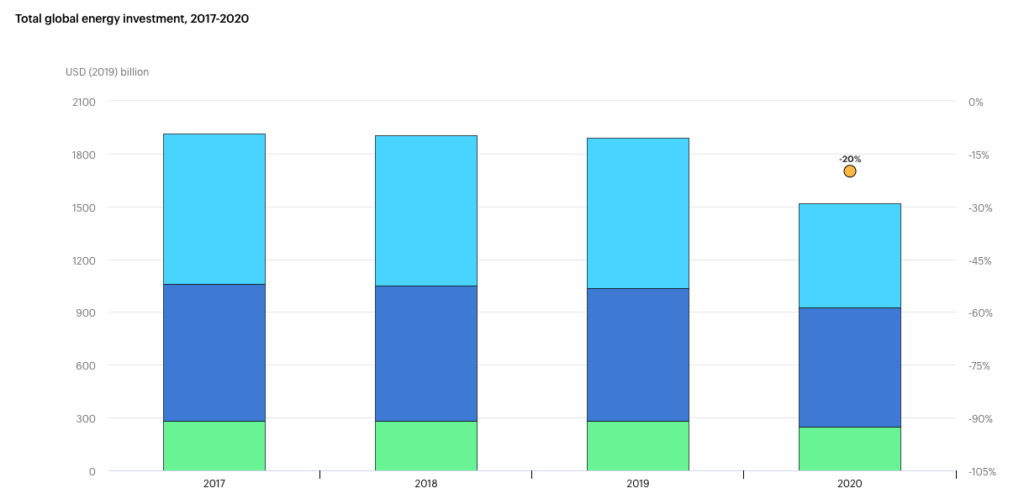

“At the start of the year, our tracking of company announcements and investment-related policies suggested that worldwide capital expenditures on energy might edge higher by 2 percent in 2020. This would have been the highest uptick in global energy investment since 2014. The spread of the Covid-19 pandemic has upended these expectations, and 2020 is now set to see the largest decline in energy investment on record, a reduction of one-fifth—or almost $400 billion—in capital spending compared with 2019.

“Almost all investment activity has faced some disruption due to lockdowns, whether because of restrictions on the movement of people or goods, or because the supply of machinery or equipment was interrupted. But the larger effects on investment spending in 2020, especially in oil, stem from declines in revenues due to lower energy demand and prices, as well as more uncertain expectations for these factors in the years ahead.”

Phil Flynn, senior market analyst at Price Futures Group, was quoted on FoxBusiness.com today discussing these very conditions, and IEA’s assessment of them.

Flynn remarked that “Millions of barrels of future oil supply will not be there as the industry recovers from its trillion-dollar Covid 19 hit. Oil traders know that as demand comes back, supply will tighten, and it looks like the market will be in balance in just a few months justifying the oil markets’ historic price snapback. Demand is rising and production is falling.”

Flynn said that the market is showing signs of coming back at a much faster pace than expected.

“All of this would suggest that the world is going to see the global oil oversupply start to disappear as long as we don’t take a big step back with another trade war,” Flynn said.

Meanwhile, through all of this, oil and gas have taken a bashing. Not just by the marketplace, but by the investment community.

What too often gets ignored in all this turmoil is the plain fact that oil and gas are commodities. As such, their prices are not set by producers themselves. That means that a different dynamic exists for oil producers as opposed to, say, makers of cars or makers of light bulbs.

Car makers can build their cars and set their own prices, and if the public doesn’t flock to their offerings, those same makers can trim their prices a modest amount (and likely get sales). Or if the car maker thinks that economic conditions, and not the attractiveness of their car deals, are the operative factor, then the car maker can just sit out the lull and hold their cars in inventory and hope that a few weeks or months will make a difference. In either case, though, it is the car maker who sets or maintains the price.

Not so with commodities like crude oil. They must answer to a commodities price that is set by global conditions, and that is independent of the oil producer’s own choices or actions. That price can swing wildly and the oil and gas producer must live by it and die by it. There’s little flexibility to hold back one’s inventory. All, or almost all, must be fed into the system and one must accept the results, whatever they may be.

This being so, a company that produces a commodity should not be judged on the same scales as one that manufactures a product or provides a consumer service. Nor should the executives who run a commodity be bashed for presumed “poor management” when conditions that are beyond that executives’ control cause the company to be operating at an extreme deficit.

But is that not exactly what happened when, some 2-3 years ago, Wall Street began to sour on investments in oil and gas, citing underperformance in the market? The mantra that we were hearing then, and still are hearing, to some extent, is that oil management has made bad decisions and that oil producers need to henceforth power themselves via their own cash flow.

Well, certainly it is true that in a collapsed price market, any oil enterprise is not going to look attractive, for the short term, to outside investors. And if an investor wants to stay away, during a time of depressed prices for a commodity, that is certainly that investor’s own choice to make.

But what was particularly grating about remarks we’ve heard from Wall Street about the ill-advised-ness of oil investments is the suggestion that the oil business is in the fix it is in because of companies’ poor management.

Oil companies cannot project the future with anything near the accuracy that a car maker can, or a light bulb producer can. When oil sells at $100 a barrel, almost every CEO is a mastermind. When it sells for less than $20 a barrel, every CEO is a dud, guilty of not delivering a good return on capital investment and guilty of being a poor choice for fresh capital infusions. But are those executives truly as much at fault as Wall Street would appear to be saying?

Let the price for oil climb into the high two figures and then let’s see who the good managers are and let’s see where the money flows

The fact is, every crisis holds the seeds of its own solution.

The only recourse that oil and gas producers have is to decline to invest deeper, or commit heavier, into more production.

That’s a far different thing that simply tweaking one’s product price, as a maker of light bulbs can do, and it is a different thing than holding onto one’s price and one’s inventory until buyers warm back up to one’s offerings.

With commodities like oil, the harder that the marketplace batters the industry, the deeper it plunges, and the deeper it plunges, the stronger it (eventually) rebounds. It’s all a function of supply-and-demand. We’ve had record oversupply in recent months.

That has led to record cutbacks and retrenchment. Such steps always lead to swift reductions in supply. Swift reductions in supply lead to significant undersupply, and undersupply brings on sharp increases in demand, and with demand comes higher prices. All those eventualities are already in process. It’s just a matter of time until the pendulum swings all the way to the other end, and producers of oil and gas get their due. Let’s hope they get something more than that, as compensation for a battering they’ve taken from the marketplace and even from a less-than-appreciative Wall Street.

So that is where crude oil’s salvation lies. And that is the revenge that commodities markets always get, eventually. They get battered by price dips that they cannot control. But in taking their lumps and curtailing their expenditures and efforts, they plant the seeds that will later sprout as their comeuppance.

Meanwhile, though, the O&G industry must endure its trials.

It seems that the harder that commodities get hit, the harder they rebound when, eventually, they rebound, as they always do. And we can invest some hope in that prospect. The deeper the valley we must endure, the higher the peak that we should top.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

By Jesse Mullins

Terrific article!