Observers expound on what the recent lifting of the crude oil export ban could mean to the U.S. energy climate.

Julie Anderson

On Dec. 18, 2015, the United States of America lifted a 40-year-old ban on exporting crude oil, put in place in 1975 in response to the Arab oil embargo.

While the vehicle used to lift the ban caused some frustration among members of the Permian Basin Petroleum Association (PBPA), “in the end, we were pleased with the result,” shared PBPA President Ben Shepperd. The legislation ending the ban was rolled into the Omnibus Bill, which included a host of other measures that were not well-liked by many in the industry.

The goal of lifting the ban was to provide an open market for American’s light, sweet crude oil for use in properly equipped refineries in Latin America, the Caribbean, and across the Atlantic, Shepperd explained. This move eliminated the discount inflicted upon West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil compared to the strong global pricing that Brent crude oil has long enjoyed as the international benchmark for oil prices.

“Since the President signed the bill, the spread between WTI and Brent has decreased dramatically,” Shepperd noted.

The Effects of a 40-Year Ban

On Feb. 3, 2016, PBPA Immediate Past Chairman Steve Pruett, president and CEO of Elevation Resources, LLC, testified before the Texas House Energy Resources Committee during an interim hearing to study the impacts of declining oil prices and energy development strategies.

During his testimony, Pruett laid out the history of the ban and explained to Texas lawmakers how the ban has affected U.S. oil prices.

The U.S. Congress passed the ban on oil exports in 1975 in reaction to the Arab Oil embargo of 1973; the result was a spike in average imported oil prices of $3.22 per barrel in 1972 to $12.52 in 1974, peaking in 1981 at $37 per barrel ($100 per barrel in today’s dollars) following the Iranian Revolution, when Iranian oil production declined by 4.8 million barrels per day, 7 percent of world production at the time (www.eia.gov).

Upon signing the Energy Policy and Conservation Act into law on Dec. 22, 1975, then-U.S. President Gerald Ford stated, “The time has come to end the long debate over national energy policy in the United States and to put ourselves solidly on the road to energy independence… This bill is only the beginning.” The law, which constituted a ban on most U.S. oil exports, has remained a topic of energy debates for four-plus decades.

“Our government was rightly concerned about access to and the cost of crude oil, as Middle Eastern countries were using oil as an economic, if not strategic, weapon,” Pruett said. “The United States was battling runaway inflation and high interest rates in the late 1970s, battering our economy. It was a matter of our national security.”

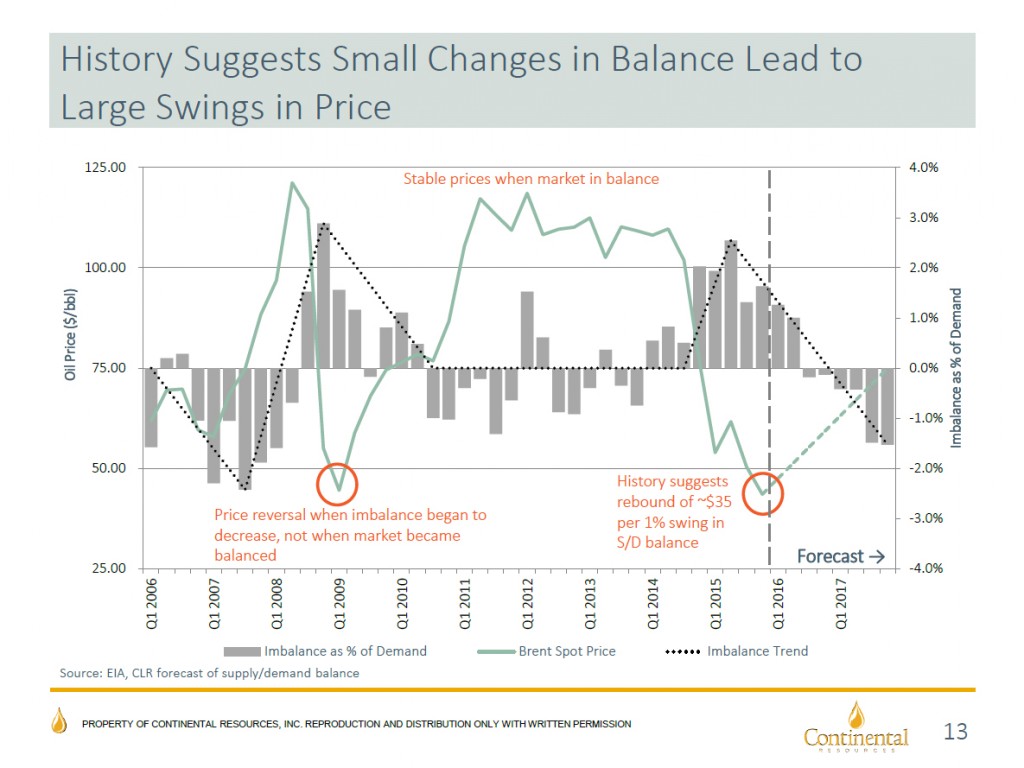

As time went on, high oil prices stimulated global investments in drilling and technology that created a glut of oil, driving prices down to $11 per barrel in 1986 and again in 1998, reducing oil industry investment and employment.

“Both times OPEC, led by the Saudis, decided not to cut oil exports in a time of global excess, and oil prices collapsed,” Pruett summarized.

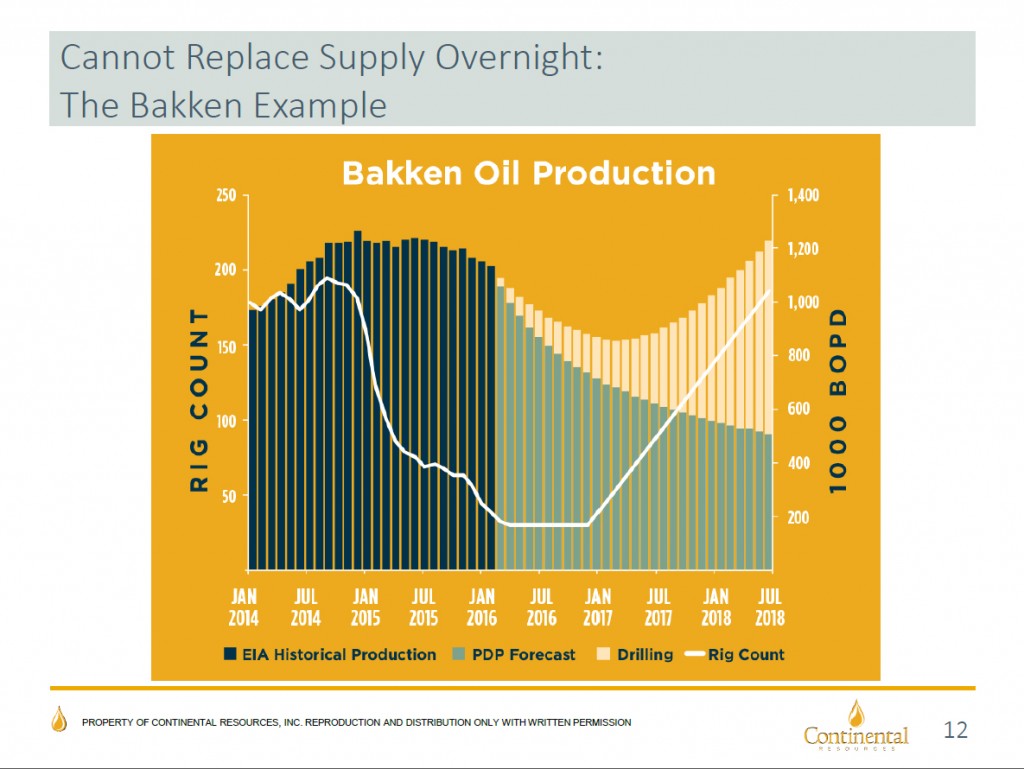

Flash forward several more decades, and high oil prices once again stimulated investment and the development and application of technology in the oil industry, creating excess global supplies of oil.

“In particular, the United States developed an excess supply of light, sweet oil produced from tight shale formations that could not be exported,” Pruett detailed. “Oil prices have declined from approximately $100 per barrel at the wellhead [price E&P companies receive] in June 2014 to $25 (75 percent decline), and now $40 per barrel, crushing the U.S. oil industry’s revival due to horizontal drilling with multistage hydraulic fracturing of shales and other tight formations.”

Sweet Versus Sour

Another factor affecting oil prices was and continues to be the refining capacity of light, sweet crude versus heavy, sour crude.

Historically, WTI Cushing, the basis for pricing oil produced in the United States, traded equal to or at a small premium of $0.50 to $1.50 per barrel compared to Brent oil prices. WTI Cushing traded as wide as $23 per barrel below that of Brent oil prices during 2013 when WTI traded over $100 per barrel.

“This was because of the glut of WTI produced from tight shales compared to the refining capacity for our premium light, sweet crude oil that was coveted prior to the mid-1990s when the refiners spent billions to convert their refineries to process heavy, sour crude produced in Mexico, Venezuela, and Saudi Arabia,” Pruett recounted. “The irony is that refiners such as Exxon, Shell, and Valero made the investments due to the decline in light, sweet crude oil in the United States to less than 4 million barrels of oil per day.

“Most of the new sources of imported oil in the 1990s were from the heavy, sour crude that sold for a discount [compared] to light, sweet crude oil,” Pruett said. “The oil produced from the shale formations and tight conventional formations in the United States is light, sweet oil.”

Sour oil contains sulfur, which must be removed at considerable expense from oil when it is refined into gasoline, diesel, jet fuel, and other products since it is a pollutant and corrosive on engines, Pruett said. Sweet oil does not contain sulfur and is cheaper to refine, but the refineries were modified to remove sulfur and upgrade heavy oil, and preferred the heavy, sour oil to light, sweet oil once the investment was made in the heavy oil cracking units and sulfur extraction processes.

A Convergence of Factors

What prompted the lifting of a ban that has remained in place for four decades? Shepperd cites a mix of factors, including geo-political, market availability, national energy security, refinery capacity, and abilities at home and abroad.

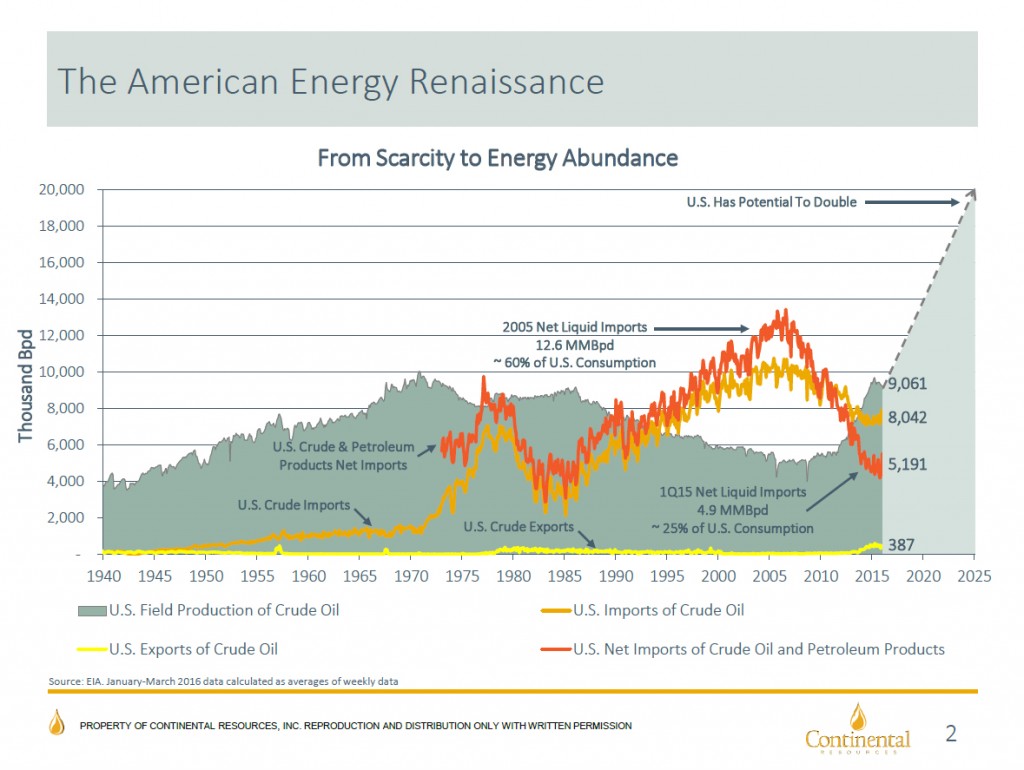

“The spur, however, was probably the large increase in domestic production over the past several years,” Shepperd emphasized. “Without that production, the geo-political gains would not have presented themselves, the future of our national energy security would not have been so protected, and the need to find refineries that could process the immense amounts of light, sweet crude now available wouldn’t have existed.”

The lifting of the ban on oil exports was accomplished through a compromise with its opponents by granting another five-year extension on tax credits (subsidies) to wind, solar, and other forms of alternative energy, Pruett explained.

While some politicians and journalists claim the oil industry receives tax subsidies, this is not true, Pruett declared. Rather, the oil industry, like every other business that invests in projects, recovers capital investments through depreciation, which serves to reduce taxable income.

“Tax credits are direct reductions in taxes due,” Pruett maintained. “In other words, a dollar invested in a wind or solar project reduces a dollar of taxes immediately, where a dollar invested in drilling a well reduces taxes by 35 cents [the tax rate on corporate income] over a period of years.”

Direct and Indirect Impact

When it comes to analyzing any aspect of the oil and gas industry, analyst Morris Burns points to the fundamentals: supply and demand.

Storage tanks are too full, Burns stated. When storage goes down, the price goes up.

“We are shipping out some excess that we had in storage,” Burns observed, “and that is affecting the prices. Anything that drives the price up will help.”

Since Congress lifted the export ban, Texas oil has since been exported to Mexico, the Caribbean, and to Europe, and has eliminated the price discount of WTI compared to Brent, Pruett said.

While exporting has only just begun, meaning additional impact will be analyzed over time, Harold Hamm, chairman and CEO of Continental Resources, points to a long list of benefits that he believes will help America claim a leadership role in energy world.

Hamm, who testified numerous times before Congress in support of lifting the ban, cited oil exports as a “Victory For America” during a presentation at the Oil and Gas Investor Energy Capital Conference on Mar. 29.

Hamm said U.S. oil exports are already reshaping the world energy landscape and will lead to American leadership in the energy world by (1) aiding our allies with a stable source of crude, (2) reducing our European allies’ dependence on Russia, (3) ending OPEC dominance once and for all, (4) de-intensifying the Middle East’s strategic importance, especially Iran, (5) putting Americans back to work to the tune of 400,000 jobs a year, (6) getting America off of foreign oil, (7) lowering and stabilizing gasoline prices for consumers, (8) providing opportunity for energy independence by 2020, (9) adding 1 percent to GDP growth, and (10) drastically reducing the U.S. trade deficit.

“We can once again be the growth engine of the world for the next 50 years,” Hamm stated, “as we were post-World War II.”

Julie Anderson, based in Odessa, is editor of County Progress Magazine, and is well known to many readers of PBOG as the former editor of this magazine.