Not everything is doom and gloom. Some innovative companies are actually thriving as prices fall.

By Paul Wiseman

“This boom is different from the others—it’s technology driven,” was the oilfield mantra from 2010 through 2014. And while that boom did prove to have feet of clay like the others, it is indeed different in that the touted technology has engendered efficiencies that have prolonged at least some aspects of the boom even as prices have fallen.

Three Midland companies are among those that have actually prospered because they offer technology and/or services that reduce various aspects of operating costs and overhead for price-squeezed oil companies.

Production Lift Systems, Inc. (PLSI), JetCEO, and Texas Energy Raters have all at least doubled their business since the beginning of the oil price free fall and are optimistic about the future. While all three are helping clients become more efficient, each has a distinctly different approach.

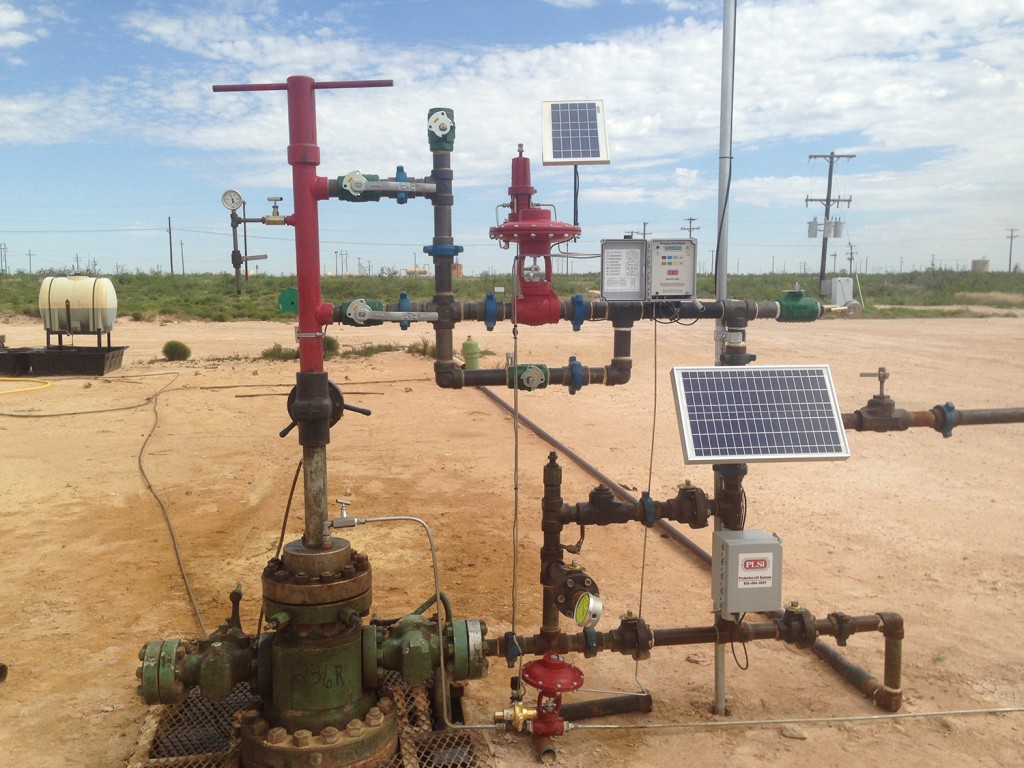

PLSI’s journey to growth actually started about two years ago when they began to see how to expand the way plunger lift could be used. Always the least-expensive artificial lift method because it requires no pump and little maintenance, conventional plunger lift was limited to wells producing no more than 100-200 barrels of fluid per day.

Plunger lift works by inserting said plunger into a well’s tubing. Liquids (oil and produced water) collect on top of the plunger, which is pushed to the surface at regular intervals by the well’s downhole pressure. Conventional plunger lift is responsible for virtually all of the liquid production.

About two years ago clients approached PLSI President and CEO Mike Swihart with a proposal to try using plunger lift on much higher capacity wells. Swihart admits to thinking they were crazy at first, but with some design changes in the plunger and much trial and error, they eventually progressed to a 90 percent success rate on wells that produced as much as ten times the “textbook” plunger lift volume limits. Most are producing around 300-500 barrels per day.

They’ve had the most success in Southern Delaware Basin wells that have enough pressure to produce themselves most of the time, needing just occasional help from a specially designed two-stage plunger. Swihart reports that the new plunger cuts lifting costs by up to 90 percent in applicable wells.

Even the conventional plunger lift business has increased over the last few months, but Swihart attributes 75 percent of the company’s growth to the two-stage version. “It’s the biggest part of what’s happening to us because that’s where the big money is,” he said.

New wells often flow on their own for a while, he said, but as soon as they “start to die” producers look for the most economical way to continue production. Economy is always a factor, but in today’s price climate, some producers have been willing to think further outside the box, and PLSI has benefitted from this.

The updated design is still new enough, says Swihart, that most producers don’t consider it. As the word spreads and the idea catches on he feels PLSI’s business could grow tenfold more. “Between the wells that are aging, plus all the horizontals that they’re bringing on right now,” the potential for growth is huge. Right now, “I would say 75 to 80 percent of the industry is not aware of what we’re doing here,” at least not yet, he said.

The growth potential is actually almost frightening. “A year to two ago, when it started dawning on me what we’re looking at here and what we’re biting into I realized we could be overwhelmed [with growth] almost next week,” Swihart recalled. In short order he quadrupled the size of the organization, including wireline, swabbing, field service, and other non-plunger lift services, and added on to the existing facility. The company now employs approximately 60 people, making it as large as it’s ever been.

Slow Times Make More Time for Safety

At least one company has benefitted from the slowdown simply because potential clients now have time to talk—and the company does help boost revenue by identifying vapor loss that, when located and repaired, increases the product available to be sold.

Thermal Cam, a subsidiary of Texas Energy Raters, does infrared (IR) and optical gas imaging OGI surveys to find these leaks. Says company President Peter Walper, “We have a FLIR GF320 (camera) with which we’ll shoot a valve or shoot a tank to see the gas escaping from the pop-off valve or wherever it’s leaking.” Repair crews can then find and repair the located leaks.

Technicians use the IR camera to shoot electrical panels at well sites looking for heat-related anomalies that indicate the need for preventive maintenance before something irreversible happens. They also use the IR camera to track bearing temperatures in mud pumps, realizing that rises in bearing temperatures mean an increase in friction caused by progressive wear on those bearings. That way the company can rebuild the pump before it breaks down.

Most of the company’s clients are smaller companies because the larger ones have can afford to buy these $100,000 cameras and pay employees to operate them full-time.

Along with the revenue side, Thermal Cam is tapping into a renewed concern for safety on the part of producers. “Safety is a big factor now, where people have time to look at [it],” said Walper. “They want to reduce risk, so they’re looking at electrical panels, doing preventive maintenance,” or seeing leaking gas as not only a lost asset but as a potential safety issue. It doesn’t hurt that the EPA, Texas Railroad Commission, and other regulatory agencies are watching greenhouse gas emissions more closely as well.

Logging a problem, even if it can’t be fixed immediately, buys time with regulatory agencies. “You want to keep ahead of that and put together a preventive maintenance plan so that, if the Railroad Commission comes by and says, ‘Hey, looks like you’ve got a gas situation here,’ you pull out your preventive maintenance program and say, ‘Yeah, we’re on top of that,’” Walper explained.

Slower times have allowed producers time to think—and to think about safety in particular. “A couple of years ago, when everybody was blowing and going, nobody had a minute, they couldn’t even talk to us because they were so busy they couldn’t stop and look,” Walper noted. “Now, when things have slowed down, they’re saying, ‘Hey, we need to call that guy back.’ Hopefully, we’ll get busier and busier.”

It might look like a typical wellhead, but there’s something special going on. PLSI (Plunger Lift Systems Inc.) installed its innovative two-stage plunger system into the well’s tubing. This system cuts lift costs by about 90 percent. And meanwhile ramps up output to “turbo” status.

They’ve recently added another camera and two more trucks, along with the personnel to operate them. The company now has five employees in the field operating five trucks, and two in the office.

All this is geared to handling business that has tripled since the beginning of 2015, with still a good outlook for more growth. “I don’t think we’ll be at 100 employees overnight,” Walper mused, “There’s plenty of work out there, I think.” Companies in similar businesses in Canada and east Texas, he said, are already swamped, and the wave of business is now beginning to sweep into West Texas as well.

Because Thermal Cam provides companies with an independent third-party evaluation, which is important to regulators, Walper expects business to continue to expand whenever oil prices come back up.

The Jet Set is Not Grounded

One might expect a downturn to send corporate travel into a tailspin, but that’s not the case—it’s just adapted and gained new efficiencies. JetCEO owner Joshua Lorenz, a pilot himself, manages corporate aircraft and travel for clients who typically own small to medium size oil patch businesses, or are retired from the same. They travel across Texas or nearby states, with an occasional venture to either coast. Their travel is typically divided 50-50 between business and personal, with personal ranging from ski trips to visiting grown children who are working or going to school elsewhere.

The four-year-old company began with Lorenz selling aircraft and consulting with clients looking to purchase aircraft. Much as with PLSI, it’s been a recent change in the business model that has been the key to JetCEO’s current round of success. “In the last two-and-a-half to three years it’s really become an aircraft management company, Lorenz said. “If I was going to describe my business to you in an elevator, I’d say we do three things; we do aircraft consulting, brokerage, and management.”

Many executives become frustrated with the limitations of commercial airline schedules and locations—many times needing to go someplace where a commercial jet couldn’t land anyway. But buying, owning, and maintaining a corporate jet is a complicated undertaking, and that’s where JetCEO comes in. Lorenz is often told, “I just want the cheapest plane you can find,” which he discourages. Flying to Houston in a cheap plane is a whole different proposition from driving to H-E-B in a ’75 Pinto. For one thing, it’s really hard to sell a cheap one when you’re through with it.

Instead, Lorenz starts with customers by establishing a mission profile—in other words, what will you use the plane for, how often, who’s riding with you, where will you go? Budget does come into play. Then he does a profile of aircraft to see which one is the best fit for those requirements.

The next biggest question regards who will fly the plane. Very few executives fly their own, so most must find a captain or pilot. This is not as easy as standing outside the exit door at a flight school with a handful of applications.

“We go through a pretty heavy due-diligence period of finding the right captain,” he said. “In order to hire a good pilot we would interview 30-50 qualified candidates and probably look at 150 resumes.” Getting the right one involves not just experience but the right kind of experience, temperament, and other factors.

Then there’s finding a hangar, as well as getting registration, maintenance, and other things that most people don’t know about nor have time to deal with.

Lorenz says his business has doubled because, while executives still need to travel, they want to explore more cost-effective options. JetCEO is open to newer and more fuel-efficient aircraft, which at the same time have a strong safety record.

There are also ways to share the cost, which Lorenz refers to as partnering. In this model, several owners simply share the cost of ownership, including maintenance, licensing, and all else, along with paying for their own trips. The older model, known as fractional ownership, involves the user paying large hourly fees for use of the plane.

If there is one moral to this story it would be that finding ways to improve the bottom line while actually boosting quality can be the very thing that boosts business when oil prices fall. The above companies, which have doubled, tripled, or quadrupled sales already and are seeing sometimes frightening opportunities in the future, have done just that.

Paul Wiseman is a freelance writer in Midland, Texas.