Care and Grooming of a Frac Sand Mine

An acute driver shortage can almost be categorized as infrastructure challenge as well.

By Paul Wiseman

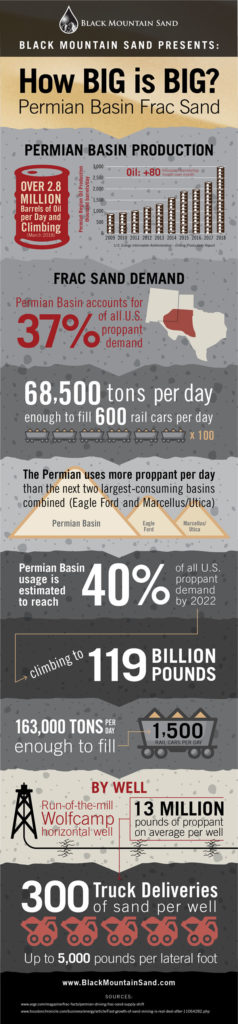

Reminiscent of the 1889 Oklahoma Land Rush, the 2018 Permian Basin sand rush saw excited investors descend on the Basin, opening approximately 19 new sources of this granular gold. Black Mountain Sand opened three of those 19: the Vest Mine, source of what they call “Winkler White,” which opened in January near Kermit. Their El Dorado mine, also near Kermit, opened a few months later, and the Sealy Smith facility, located near Monahans, was the third.

The process of finding usable sand then securing its availability is complex, spreading over multiple years and involving geology, land work, and development.

Hayden Gillespie, chief commercial officer for the two-year-old company, explained how it all works.

To start with, “We’re looking at all the available maps that are out there, whether they’re USGS maps or state surveys—any kind of publically available maps.” Gillespie said.

A worker monitors activity at one of Black Mountain’s mines. Sand is big, and it has not only created jobs but has created new kinds of occupations.

When those investigations reveal an area that might hold sand of a quality and proximity to wells that would make it profitable, Black Mountain goes into an acquisition phase.

“We approach landowners, we try to figure out what we’re looking at (on) ownership maps, we’re looking at potential lease options,” he said. They speak with landowners about test agreements to determine if usable sand is on their land and, if so, in what quantities. Coring rigs in West Texas grab columns about 120 feet deep in order to understand the deposit’s characteristics.

“Is it homogeneous, are we seeing differences in the mesh distribution as we go to different levels, what are we seeing in terms of overburden [or topsoil and organic levels including grasses]?” Gillespie said they’re also looking for the level of the water table.

“The next phase is equally, if not more important, especially in West Texas” said Gillespie, “is understanding the infrastructure.” Access to water, natural gas, electricity, and roads are important to understand before moving ahead. Locating either on an overcrowded county road or an unpaved track, both create access problems that “decreases the value proposition.”

He continued, “We probably drilled 600 core holes across Winkler and Ward counties. We acquired about 29,000 acres in probably 5-6,000 acre contiguous blocks.”

Gillespie compared their analysis procedures to those of an E&P company assessing an area’s rock formations to help them decide whether to lease it for drilling.

“We kind of [assessed] our asset base and said, ‘This particular area that we’re in, we like this spot right here because it generates the deposit we like, the mesh distribution that we like, as well as the ease of access, and the proximity to good infrastructure.’”

Their two flagship facilities are on State Highway 302. “We get access to the Midland Basin real easily, we can access the Delaware Basin, we can go north and south easily.”

Like other frac sand companies, they worked with TXDOT and MOTRAN to assess the road’s ability to handle frac traffic. “We completed a couple of projects with TXDOT in order to improve the ingress and egress from our facility.”

After working with MOTRAN, Black Mountain will also contribute funds to the widening of 302 to four lanes throughout the area accessed by the two mines “so we’ll have a really efficient roadway to access our facility.”

Anticipating challenges well in advance and working through public-private partnerships helps ensure efficient operations as well as safety for all traffic in the area, Gillespie said.

“Access to water, natural gas, electricity, and roads are important…” —Gillespie

Access to electricity is a pretty obvious need for any enterprise, but natural gas is also key for frac sand mines. “We employ natural gas for the purposes of powering our driers, but also, in addition to permanent three-phase power that connects to our facility, we use backup generators which are powered by natural gas.”

“We probably drilled 600 core holes across Winkler and Ward counties.” —Gillespie

An acute driver shortage can almost be categorized as infrastructure challenge as well. Black Mountain is addressing that indirectly, by structuring their loading process so each truck can be filled in 10 minutes. Speeding the process can allow the drivers that are in place to make more trips per day. Increasing efficiency, said Gillespie, is “the next big thing” in the frac sand sector.

For a while now the Permian has played host to more drilling rigs than any other area in the United States. One might wonder if other, less active areas are easier places in which to open and operate—well, anything, including a sand mine.

“A lot of the challenges are the same, when you think about it. The site selection is pretty much the same way, you want to find a really good deposit, you want to find it in good proximity to your customers’ work, and infrastructure in place,” Gillespie said. “Once you develop a really good blueprint, [you can] continue to run those plays in a different Basin.”

“Each site comes with its own set of challenges,” he continued. “Whereas labor force is really tight in the Permian Basin, in the Eagle Ford and in Oklahoma you have really good access to stable, non-transient workforces. That really enables us to give [good] service.” Pipeline constraints don’t exist elsewhere, either.

A big takeaway for Black Mountain, fueling its entry into other basins, is the idea that suitable and plentiful frac sand can be found close enough to almost every basin—which reduces completion costs by as much as a half-million dollars per well. It also alleviates a long list of logistics headaches and shipping delays involved in Northern White or even Brady-area sand.

For example, “In the Eagle Ford, there’s a deposit that is fit-for-purpose that will work in these shale plays. So we see customers creating demand for those products—and to the extent that the demand is there, we’re going to build and produce sand.”

Boom-and-bust cycles that push producers toward automation-enabled efficiencies to cut overhead also drive them toward cutting frac costs with nearby sand. “Born out of the downturn was this idea that… the lowest cost and most efficient option will always be the preferred choice,” Gillespie said. In other words, during a downturn the more distant sand mines suffer first and worst, while localized mines come closer to holding their own.

With current operations in the Permian, in the Eagle Ford, and in Oklahoma, Black Mountain plans to add mines in Colorado’s DJ Basin and the Powder River Basin eastern Wyoming. In November of 2018 there were about 35 rigs in the DJ Basin and the Powder River Basin had approximately 24.

Many experts believe Permian production will continue to rise over the next 10 years, so there should also be a continued sand rush in this area.

Paul Wiseman is a freelance writer in Midland.