By Julie Anderson

Imagine an intruder found a small hole through which to snake a video device into your home. Throughout the next week, the invader deftly wound the video probe through each room and closet of your house, finding valuables both large and small. Then, one day you left your travel plans in clear sight of the probe. Finally, when you were miles away the intruder took his meticulous notes and breached your home, deftly and quickly grabbing your valuables in a well-orchestrated breach, in and out before the police arrived on scene.

Now imagine that home is actually your computer or your company’s network of computers. The intruder goes undetected, watches and waits, determines the most dangerous time to strike (dangerous for you, that is), and attacks. According to cybersecurity expert Anantha Bangalore, here’s what could happen:

plant shutdown;

equipment damage;

utilities interruption;

production circle shutdown;

inappropriate product quality;

undetected spills; and/or

safety measure violations resulting in injuries and even death.

“It is not enough to rely only on detection-only security solutions,” declared Bangalore, who has 18-plus years of experience in design, analysis, and information systems and now serves as chief architect with SCIT Labs. Self-Cleaning Intrusion Tolerance (SCIT) references the lab’s patented technology that works like a digital vaccine to offer proactive cyberattack deterrence.

“Once a system has been compromised, an attacker stays in the system for months, having substantial time to steal data and do damage.” Such is the warning supplied at http://www.scitlabs.com/products-solutions/technology. “Once they are in, they learn how your systems operate, where your most valuable assets are located, and how to get your data out of your system under your security radar.”

Cybersecurity Breaches

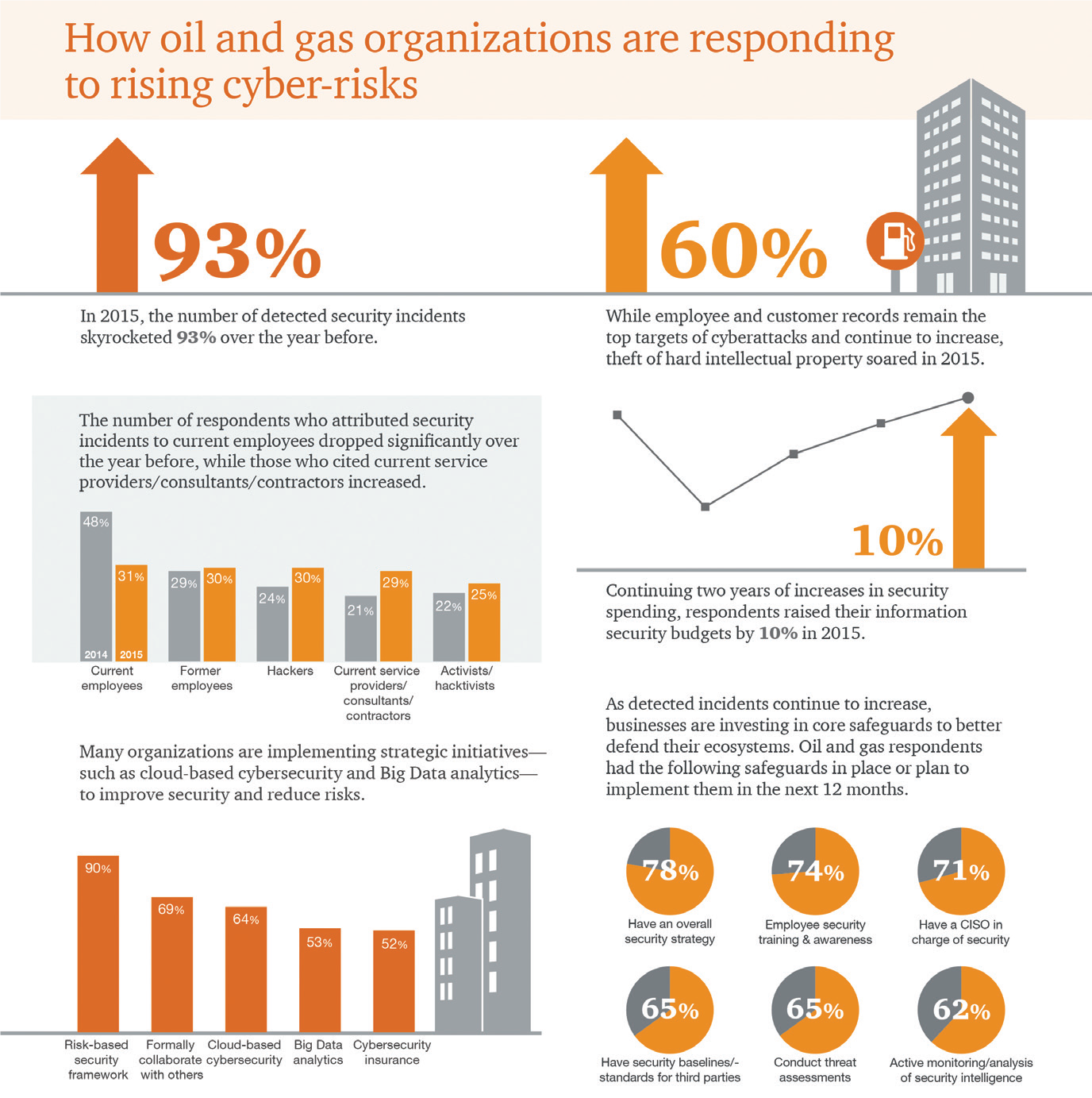

PricewaterhouseCoopers, a multinational professional services network headquartered in London, offered the following key finding following its Global State of Information Security

Survey of 2016: “In 2015, organizations reported a 93 percent rise in detected information security compromises. On average, oil and gas businesses reported more cybersecurity incidents than any other industry.”https://pwc.to/2HIXjxt. “Among this global surge in compromises, oil and gas businesses understand that they should treat cybersecurity as an operational imperative—on par with health, safety, and environmental effort—to better manage risks.”

The oil industry is a core component of the nation’s critical infrastructure, Bangalore observed. “A cyberattack on this infrastructure can lead to destabilization of a country’s economy,” he emphasized. “Components that control plant environments are increasingly being interconnected and placed on the internet to enable remote monitoring and control, and this makes them vulnerable to hacking,” Bangalore said. “Firms in the oil and gas industry are particularly vulnerable because manipulation of their plant environments by malicious actors can result in significant damage. There are also strict controls on the use of seismic data; some of it is saved for decades, thus legacy system protection is a major challenge for oil and gas.”

Bangalore’s perspective is not based on conjecture but on previous incidents and resulting data. For example, in 2016 energy was the industry second-most-prone to cyberattacks, with nearly three-quarters of U.S. oil and gas companies experiencing at least one cyber incident, http://bit.ly/2FEZccH. Specifically speaking, hackers began targeting oil and gas companies years ago. For example, in mid-2012 a computer technician on Saudi Aramco’s information technology team opened an email and clicked on a bad link; with one press of one button, the hackers were in. Within a matter of hours, some 35,000 computers were partially or completely destroyed. The domino effect was, in some ways, catastrophic. Gasoline trucks in need of refill were turned away, and Saudi Aramco resorted to typewriters and fax machines as they tried to regain their technological footing.

Bangalore cited other incidents, including the 2011 cyberattack dubbed “Night Dragon,” in which hackers stole exploration and bidding data from oil majors, including Exxon Mobil Corp. and BP Plc. Past assaults in 2012 and 2014 crippled companies throughout the Middle East and Europe with disk-wiping malware and advanced Trojan Horse attacks.

Oil and gas companies, like other firms, also store confidential information, including employee, customer, and financial data, Bangalore emphasized, making it clear that cyberattacks can affect workers on a personal level. SCIT Labs has analyzed the major security breaches of the 21st century in an 11-page report at http://scitlabs.com/images/pdf/major-security-breaches-final.pdf.

Hunton Andrews Kurth LLP’s Energy Sector Security Team also cited the Saudi Aramco attack as a key example of the need for cybersecurity, labeling the incident as “the most destructive known cyberattack on a single company.” It required the replacement of 75 percent of the corporate computers.

The Energy Sector Security Team assists companies in protecting the security and resilience of their critical infrastructure facilities in the face of these physical and cyber threats. https://www.hunton.com/en/industries/energy-sector-security-team.html.

“Cybersecurity is an important issue for any industry, but particularly those industries with critical infrastructure that provides the public with important services,” stated Paul Tiao, partner, and associate Eric Hutchins, both of Hunton Andrews Kurth LLP.“The energy sector, and specifically the oil and gas industry, is rightly concerned about cyberattacks.”

Specific Industry Challenges

It is difficult to generalize about cyber vulnerabilities across oil and gas companies, as that assessment depends on how security measures enacted by each company align with threats posed by malicious actors, noted Tiao and Hutchins.

“However, it is clearly the case that the cyber risk to oil and gas companies is growing as sophisticated threat actors are focusing on the oil and gas sectors and enhancing their techniques, tools, and procedures for launching cyberattacks. For example, advanced persistent threats, often in the form of foreign nation states, have specialized teams devoted to each element of the hacking process—with experts in areas like surveillance, social engineering, malware development, and payload deployment.”

Oil and gas companies are primarily concerned about attacks on operational technology and industrial control systems that could disrupt the flow of oil and natural gas or result in catastrophic malfunction, Tiao and Hutchins reported. However, while high-impact-low-probability “electronic Pearl Harbor” scenarios may dominate public attention, oil and gas companies are more likely to experience cyberattacks more commonly faced by other companies. This could include exfiltration of confidential business or personally identifiable information, ransomware attacks denying use of systems on the corporate (as opposed to operational) networks, or politically motivated activities.

“Indeed, the House Science Committee released reports documenting Russian attempts to ferment discord on pipeline policy through use of social media,” Tiao and Hutchins underscored.

In a 2016 cybersecurity conference geared toward the oil and gas industry, Bangalore presented the Top 10 Cybersecurity Threats for Oil and Gas as follows:

1.Lack of cybersecurity awareness and training among employees.

2.Remote work during operations and maintenance.

3.Using standard IT products with known vulnerabilities in the production environment.

4.A limited cybersecurity culture among vendors, suppliers, and contractors.

5.Insufficient separation of data networks.

6.The use of mobile devices and storage units including smartphones.

7.Data networks between on- and offshore facilities.

8.Insufficient physical security of data rooms, cabinets, etc.

9.Vulnerable software.

10. Outdated and aging control systems in facilities.

Internet of Things (IoT)

When addressing cybersecurity and the oil industry, both Bangalore and PricewaterhouseCoopers referenced gearing up for the Internet of Things Oil (IoT), a term that has grown more popular during recent years

In an article titled Internet of Things: A New Paradigm for a New World, Wipro Digital offers the following perspective on IoT and its far-reaching impact

(https://wiprodigital.com/2017/06/22/internet-things-iot-new-paradigm-new-world/)

Imagine a world where billions of IP-connected objects are sensing, communicating, and sharing information. Imagine these objects regularly collecting data, analyzing it, and initiating action—unleashing a new wealth of intelligence for planning, management, and decision making. If you can envision this place, you’ve understood the concept called Internet of Things (IoT)…

For enterprises, IoT provides range of tangible business benefits—from improved management and tracking of assets and products, to new business models, operational efficiencies, and cost savings achieved through optimized equipment and resource usage.

Across industry verticals, IoT presents an abundance of opportunities for innovation. With real-time data and potentially cross-domain data sharing, new business models can be created. And IoT can address both industrial and consumer needs. For example, the potential of IoT as a service enables new markets and value chains to build up a competitive edge. In the future, cognitive applications or systems in the context of IoT will play an even larger role.

Gartner (a leading research company) forecasts that the number of connected “things” will reach 20.8 billion by 2020. That number is massive, but the potential impacts on the ways we live and do business are even more mind-boggling. IoT will change every aspect of our world (https://www.gartner.com/en).

IoT and the Oil Industry

The Internet of Things “will bring new opportunities to advance exploration and productioncapabilities, operations, and customer engagement,” PricewaterhouseCoopers offered in its key findings/cybersecurity survey. “Similar to the convergence of operational technology (OT) systems with information technology (IT) systems, the IoT will very likely expand cybersecurity risks.

“Already, compromises of these systems are on the rise. In 2015, exploits of components like OT systems and embedded devices soared more than 50 percent. To address these risks, 61 percent of oil and gas companies said they either have a security strategy for IoT in place or are currently implementing one. In addition, more than two-thirds of respondents have established a single, central cybersecurity function that is responsible for corporate IT systems as well as connected field assets, a significant gain over last year,” according to the survey’s key findings.

While the term IoT has been around for years, the reference has become more common within the oil industry, which has become more vulnerable to cyberthreats.

Bangalore cites the following as reasons why this susceptibility has increased over the last decade:

1.More systems are connected to the Internet, allowing easier access to hackers.

2.The oil and gas industry has many legacy systems with vulnerabilities that have not been fixed.

3.Security was not a top concern of this industry for a long time.

4.Firms in the industry generally trail in implementing newer computer and networking technologies.

5.There is easier access to hacking tools and malware on the “dark web.”

6.Advanced Persistent Threats (APT) attacks by nation states have risen.

7.Nation states have massive infrastructure at their disposal to launch crippling attacks.

Addressing the Problem

Along with establishing a particular position or job function dedicated solely to cybersecurity, industry players may use outside vendors to supply cybersecurity software and programming. Bangalore recommends that companies compile a set of questions for both internal and external use.

The internal security manager should first ask the following:

a)What am I seeking to protect?

b)How valuable is it, or, in other words, what is the potential cost of not protecting the system?

c)What risk am I willing to accept? (Note that no cybersecurity system is 100 percent effective.)

d)Do employees have training in practicing “cyberhygiene?”e)Are proper access controls in place?

Potential questions to ask a vendor include:

a)How does the security product work?

b)What sort of intrusion attempts are resistant (e.g. if it requires knowledge of the malware being used, it will not work against hackers seeking to exploit zero-day vulnerabilities.

c)What is your track record? In particular, ask about cases where systems were breached even though the product was being used.

d)Please address the effort that will be required to manage the system. For example, does it require frequent updating? How frequent, etc.?

Tiao and Hutchins offered the following legal perspective when looking for a company or vendor to protect a cybersecurity system: Managers should work with their general counsel’s office to ensure that security measures are included in cybersecurity contracts. This includes, for example,

measures relating to security questionnaires, cybersecurity requirements and standards, audits, certifications, inspection rights, indemnification, and insurance, as well as requirements in the event of a cyber incident, such as timely notification, full disclosures, and coordinated response.

For additional information on cybersecurity and the oil and gas industry, see the following reports:

https://www2.deloitte.com/insights/us/en/industry/oil-and-gas/cybersecurity-in-oil-and-gas-upstream-sector.html; and

https://www.huntonnickelreportblog.com/2018/04/attacks-targeting-oil-and-gas-sector-renew-questions-about-cybersecurity/.

Julie Anderson, based in Odessa, is editor of County Progress Magazine, and is well known to many readers of PBOG as the former editor of this magazine.