Friday, May 7, 2021, may have been the wakeup call for any corporation thinking it was immune to cyberattacks of any sort, including ransomware. Alarms certainly went off in Alpharetta, Ga., then, at the home of Colonial Pipeline, the U.S.’s largest pipeline system for refined petroleum products.

After a few days and a $4.4-$5 million ransom payoff, things began to return to normal—sort of.

What won’t be normal for at least a while is the idea of some sort of herd immunity to a cyberattack. From C-Suites to the Justice Department to the Oval Office, everyone is looking for long-term solutions.

The main things at issue are how to avoid this and other internet-based shutdowns, how to handle costs, from cyber insurance to paying fines, and how to determine the extent to which law enforcement can or should get involved.

Ransomware is not new, said Jon Clay, vice president of threat intelligence for Trend Micro. The last few years have seen it become more common, even to the point of finding ransomware-as-a-service on the Dark Web. Not only are attackers getting more sophisticated, ransom demands “are getting astronomical.”

One of the top lessons from the Colonial situation, in Clay’s view, is the merging of IT (Information Technology, or back office functions) with OT (operational technology, which controls field operations). He noted that the word on the street is that the Colonial attack actually only shut down accounting, not the remote monitoring and control side. But the company decided to close everything down as a precaution—and because there would be no way to track payments while the back office system was hijacked.

“So I think, for a lot of organizations, especially those in critical infrastructure, they need to take a hard look at both sides,” Clay advised. If IT is compromised, can the system still run even without billing or visibility? The U.S.’s critical infrastructure as a whole should explore these issues as soon as possible, he said.

Ransomware hackers tiptoe along a line that separates greed from fame—how to extract the maximum amount of currency without making such a big impact that they stir up law enforcement or prompt IT people to greater diligence.

“I think the attackers didn’t realize the ramifications of what would happen in attacking the IT infrastructure,” Clay mused. “I don’t think they necessarily thought that they would take down the entire pipeline, and affect half the gasoline supply for the United States’ eastern seaboard.” As evidence of their possible panic, Clay pointed out that the Darkside group believed to be responsible quickly shut down after the episode hit the international news feed. The episode became big enough that the group feared they might have aroused the U.S. government to action.

This could have ramifications on the crime side. “For cyber criminals, you will probably see them not target these types of organizations in the future, that have so much potential downside,” Clay suggested.

On the other hand, critical infrastructure does attract some groups because its necessity to the community makes it more likely that the operators will pay the ransom quickly in order to get back online. And the growing exposure to the web would make infrastructure a prime target to an enemy.

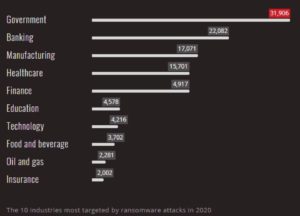

In the chart shown, the oil and gas sector was ninth on the list of the most-attacked industries for ransomware in 2020. This is indeed a significant threat.

There are several ways companies can protect themselves from this or any other cyber attack, Clay said. Since well over half of hacks originate from employees opening and interacting with phishing emails, employee training is a top priority. With phishing emails becoming more sophisticated and real-looking, he stressed that training, including the occasional sending of sample phishing emails, can make a company’s systems more secure.

After that, creating a response plan is critical. “You need to look at what would happen ‘if.’ If your IT network went down; if they got access to your OT network and it went down; if they encrypted all of your systems: would you be able to function?”

Creating a plan helps, but it should be tested through simulations to make sure it actually works.

Internal communication between OT and IT departments is also a factor for any company with cloud-based controls. Resiliency of security controls is important. Something as simple as regular and recent data backups removes the main ransomware weapon.

Next, administrative credentials should be tightened up. Theft of these credentials is another entry point for hackers, and it’s growing in popularity.

“So implementing some form of multi-factor authentication on all of your critical administrators, all your critical applications and databases that people can get access to, is key.”

How much the legal system can help is a topic of discussion as well. The Biden administration has announced several programs to try to limit ransomware. But, said Clay, many perpetrators are offshore, in nations with limited extradition treaties, so they’re hard to prosecute even when they are identified. He said officials can track movements and try to arrest the offender if and when they travel to a country with more U.S.-friendly extradition policies.

There may be comfort in knowing that there is insurance against cyberattacks now, says legal expert Sarah Stogner. An insurance coverage lawyer, Stogner has represented policyholders in insurance coverage disputes for 13 years.

Cyberattacks of various kinds began to ramp up about 10 years ago, she said. Across those years the industry began to see insureds suing their insurance carrier for relief under their general liability policies. As those cases were litigated, it became clear that “there wasn’t a product available that was intended to cover these types of things,” Stogner said.

At that point carriers clarified their forms to exclude cybercrime from general liability and created policies designed exactly for that.

Stogner had long expected these attacks on industry and in oil and gas. “I’ve been preaching for as long as this stuff’s been around, ‘Guys, it’s coming.’” She listed remotely monitored valves, handling highly combustible material monitored and controlled by computers through cloud-based connections. “That’s a target for hackers.”

Because industry doesn’t cache credit card numbers—as were involved in the Target data breach of 2013—many companies feel immune to third party liability, feeling if internal systems are damaged they can cover costs themselves.

She noted that many insiders are upset that Colonial paid the ransom, estimated at $4.4-$5 million. “But, in my mind, it’s because we’ve got a history of cybercriminals making a ransom demand that they’re actually pretty educated at making—setting the price point to get it paid.”

Of course, shutting down half of the eastern seaboard’s gasoline supply is a pretty big third-party issue, as it turns out. On that score, “I don’t know if that’s a failure of the insurance industry to explain what it covers; I don’t know if that’s a willful ignorance on the part of oil and gas companies, thinking it’s not going to happen to them.”

Of course, shutting down half of the eastern seaboard’s gasoline supply is a pretty big third-party issue, as it turns out. On that score, “I don’t know if that’s a failure of the insurance industry to explain what it covers; I don’t know if that’s a willful ignorance on the part of oil and gas companies, thinking it’s not going to happen to them.”

All this may have made cyber insurance harder to get. “I don’t know if they can get it now—they may be priced out,” she said, “especially if you get a couple more of these types of attacks.”

Buying insurance can, itself, improve security because most insurers start with a security audit aimed at reducing risk for themselves and the client. Insurance is based on the idea of protecting from a “fortuitous risk,” said Stogner, which does not allow the insured to just say, “Insurance will pay for whatever happens.” The insured has a moral obligation to do their part in reducing that risk, just as a driver must try to stay safe even if they have good insurance.

When deciding whether to pay a ransom there are other questions besides just whether it gets business going again, says Joe Dancy, a professor at

Texas A&M University School of Law in Ft. Worth. At a cybersecurity conference hosted by SMU a couple of years ago, Dancy recalled a thought-provoking question. “What if this is a terrorist organization that you’re paying off, that you don’t know? Is there criminal liability?” Dancy said the government official—which agency he doesn’t remember—said as long as the payer doesn’t know who they’re paying, there’s no liability.

In researching cybersecurity in the oil patch over recent years, Dancy said he found questions of whether industry should rely on its own standards or whether there should be government regulations, something like accounting standards. He is skeptical.

“Government-mandated regulations are interesting, but by the time you mandate regulations, virus 1.0 has mutated to virus 9.0. That was my analysis of it. By the time you have a hearing, you discuss the problem, you discuss solutions, you write the rules, you get them adopted,” things have changed to the point that the regulations may be far outdated.

Ironically, Dancy found in that context that the oil and gas industry was in favor of government regulations for two reasons. First, industry standards weren’t working—ask Colonial Pipeline about that one—and the second reason involved accountability. “If there are government regulations, and you’re fully compliant—if you do have an issue,” the company’s defense against any litigation can be that it complied with all existing rules, therefore there was no negligence.

Dancy is another industry observer, like Stogner, who foresaw and warned about this, in a paper he wrote about a year ago. If there’s one positive about the Colonial case, it’s that the industry knows for sure that ransomware is a real threat and should be motivated now to take action.

“I think you actually might see some more industry associations putting together some best practices for cyber protection,” he predicted. “We’ve had that to some extent, but I think you’ll see more of it because this is such a huge impact for so many people and it’s so visible.

Dancy is concerned that the ransom payment might inspire copycat attacks due to the fact that there are so many older and poorly protected pipelines across the county.

Plus, with Ransomware-as-a-Service lurking on the Dark Web, it has become easier for new actors to perpetrate these attacks.

Perhaps the scariest thought for oil and gas or any industry is that most IT professionals say there are only two kinds of companies on this topic—those who’ve been attacked and those who will be attacked.

Keeping systems current, communicating between technology departments, doubling down on authentication, and a bit of insurance may be the ways to at least reduce risk.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Paul Wiseman is a freelance writer in the oil and gas sector. His email is fittoprint414@gmailcom.