Dirt Work is the oilfield’s under-appreciated trade, and yet nothing gets done in the Patch until the dirt’s been worked.

by Bobby Weaver

I’ll never forget the first time I went out on a tanking job. It happened early in the summer of ’55, when we contracted to build a battery of two hi-fives in the Spraberry way down southeast of Midland. I remember turning off the blacktop, bumping across a brand new cattle guard, and wending our way for several miles through a seemingly never ending cloud of choking alkali dust raised by all the traffic along a lease road scraped out of the scrubby mesquite- and creosote-clad landscape. Along the way we passed a couple of drilling locations made pretty much like the road except for a topping of caliche to solidify the ground for all the heavy duty traffic around the sites.

When we finally got to our location the cat driver was just finishing up the pad for the tanks. That pad was about 60 feet long, 20 feet wide, and 18 inches high. It was created from dirt excavated from a slush pit off to one side along with dirt pushed up from the space surrounding the pad. After we finished building the tanks I’m pretty sure they brought in some caliche to sort of pave the area around the pad so the pumper and such would have a solid space on which to drive. It’s hard to say whether they ever caliched those lease roads but if I had to guess I would say they finally did.

As a rank boll weevil the first thing that struck me on that job, other than all that dust, was the skill of the cat operator as he finished leveling the pad and moved over to finish work on the slush pit. After we dug the tank grades and leveled the space where we were going to set them we found the surface of the pad was no more than a couple of inches off level in the 40 feet of pad space we used. Except for having stakes driven at the four corners of the pad for lineup purposes that cat operator did all of the dirt moving and leveling by eyeball. You don’t do work like that the first day on the job!

That little personal memory goes to illustrate an often-overlooked aspect of oilfield operation called dirt work. When it comes to the oil patch everybody seems to be fascinated with occupations like drilling or exotic jobs like well shooting or the importance of geological work or a host of other types of oilfield endeavors. But almost all of that activity would not be possible without the lowly work of moving dirt from point A to point B in the process of building roads, constructing drilling locations, putting up pads for tank batteries and pump jacks, and all that goes into preparing and maintaining an oilfield. The eye simply doesn’t register that vital infrastructure when it is focused on derricks or pumpjacks or other iconic images that spell oilfield to the casual observer.

From its infancy in Texas the oil and gas industry has been dependent on those dirt movers. The 1901 Lucas discovery well at Spindletop could not have been drilled without a mud pit scraped out by a local farmer, and when the well blew in—or out, depending upon your point of view—with its 100,000-barrel production, it was the dirt workers who threw up dikes to corral the oil before it drained away across the landscape. Indeed, in those days before steel storage tanks became the norm, production was stored in open pits, which were sometimes lined on the inside with cypress wood and later on with concrete. Regardless of the lining, the pits themselves were excavated by those intrepid dirt workers. There were so many of those open storage pits in the Gulf Coast area in those days that many observers noted that much of the of the region resembled a huge lake of oil.

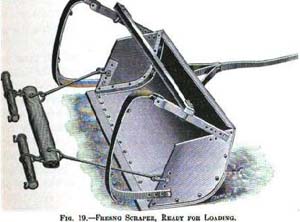

It was a time when internal combustion engines were rare and virtually all of the excavation was done using horses and mules to power what were essentially hand tools. Almost overnight huge pens quartering thousands of draft animals appeared and nearby were tent camps housing a virtual army of contractors who were fast becoming professional dirt workers specializing in the needs of the oil patch. The primary excavation work was done using small C-shaped scrapers generally called Fresnos after one of the more common brand names. The Fresno Scraper, invented by James Porteous in 1883, is generally recognized as one of the most important civil engineering machines ever devised. It revolutionized excavation work because of its ability to scrape up the soil and transport it elsewhere for fill rather than simply pushing the dirt ahead as in all previous earth moving machines. The Fresno design has become the model for all modern earth scrapers used today.

Although the oil patch has long been noted for the absence of African American workers, the early Gulf Coast region was an exception. Most of the excavation work there was done by black labor although they were housed in segregated areas in keeping with the practices of the day. All contemporaries agree that they also worked their teams differently in that they sang to the animals as they worked, which was totally foreign to the Anglo experience. In a 1953 interview Bill Kinnear, who made that boom, vividly remembered one of the more colorful scenes in that regard:

“As a rule you know, a Negro, he always sung everything he said, along before sundown especially. And in the big camps, in the grading camps, there were lots of Negros and lots of mules, why, then the Negros would go to singing, why, the mules would go to braying because it was pretty near to sundown. They made up their songs as they went and pretty muchly some of them was in the same category that they sing in the spirituals right now.”

As oil fields developed across Texas, earth moving remained an important aspect of drilling and production support, although ethnic diversity did not follow the work across the state. Although oil companies often hired local farmers to excavate mud pits at drill sites and slush pits at the tank batteries, the bulk of the work fell to professional dirt moving concerns that followed the various booms. About the only differences that developed in the nature of the work between 1901 and the late 1920s was dealing with specific problems in the nature of the geography. As the work moved farther and farther west the soil became more and more sandy and loose and instead of dealing with wet and muddy soil problems the difficulty became more how to navigate the dry sandy landscape. Those difficulties became paramount when in 1923 the drilling of the Santa Rita No. 1 a few miles west of Big Lake opened up the vast oil production region that become known as the Permian Basin.

Prior to that dirt work seldom had to contend with the widespread sandy conditions of an arid landscape. The primary concern in the Permian Basin revolved around the difficulty of transport in a region where the unconsolidated sandy nature of the soil tended to bog down most traditional means of transport while it virtually halted the fast growing number of automobiles and trucks being introduced at that time. One of the first solutions to that road problem was to begin oiling the roads graded out across the trackless region. Oiling roads to cut down on dust had been first introduced in Texas in the mid-1890s as a means of marketing the oil found at Corsicana. Since then it had become a common practice throughout much of the state as a dust controlling mechanism but in West Texas it also acted as an agent in consolidating the sandy roadbed.

The boom that developed around the discovery well quickly moved west and south to McCamey and Iraan and by 1928 it was moving north to the Crane and Wink areas. It was there that the problems became much worse. That was sandhill country, where much of the land was covered with massive sand dunes which were next to impossible to cross with wheeled vehicles. However it didn’t take the dirt movers long to figure out how to grade down the hills and oil and pack the roadways in order to stabilize them to the point that they would support the heavy traffic they had to bear. Although those solutions solved the problems of the unconsolidated nature of the land, it also forced a constant maintenance effort that continues to this day.

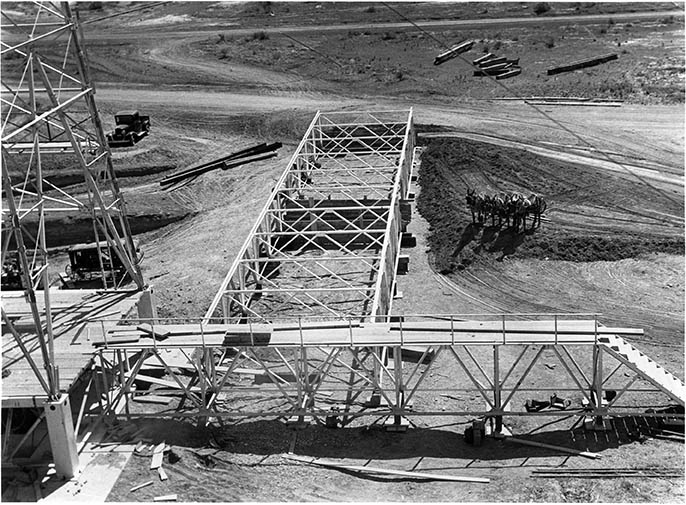

As the oilfield work continued in the region, dirt work continued to be dominated by use of draft animals for power until the late 1920s and early 1930s when they were gradually replaced by internal combustion engine powered equipment. Perhaps no other machine exemplifies that equipment better than Caterpillar. The first crawler type tractor was invented in 1904 by Benjamin Holt of the Holt Manufacturing Company. Frustrated by the inefficiency of the massive steam powered earth movers of the day, which had to be moved over plank roads to operate in the boggy San Joaquin Valley, he devised a machine that wrapped the planks around the wheels and crawled across the soft ground. One of the workers at the first demonstration of the machine observed that it crawled across the ground like a caterpillar and thus it became marketed under the name Caterpillar.

Soon after their introduction Caterpillars switched from steam to gasoline engines and in the late 1930s they introduced diesel power to their earth moving machines. Thus by the time oil activity in the Permian Basin entered the 1930s, earth moving tractors like Caterpillar as well as trucks capable of hauling heavy loads were becoming the mainstay of dirt work and the colorful days of horse drawn equipment ended.

With the introduction of serious mechanization dirt work became easier, faster, and in general more efficient. Although oiled roads continued to be used in seriously soft areas such as the sand hills, more and more caliche was used to surface roads, drilling pads, and other work areas. Since then abandoned caliche pits have become almost as abundant as jack rabbits across the region and the stone from those pits makes a significantly more stable roadbed than a little sand and oil. Today much of the region is crisscrossed by actual asphalt paved roads. Of course most roughnecks will tell you that the powers that be put off paving until the boom was over and all their crew cars had been shaken to pieces on those old washboardy caliche roads. Nevertheless, over the last several decades the work of the dirt worker has remained one of the most important albeit little known of the oilfield occupations and there is little doubt that it will continue so as long as there are wells to be drilled and supplies to be hauled.

Bobby Weaver is a regular contributor to Permian Basin Oil and Gas. His humor column, Oil Patch Tales, appears elsewhere in this issue.