Click here to listen to the Audio verison of this story!

In the September 2025 issue we share the story of the Permian Basin Petroleum Museum at its milestone 50th anniversary. What I want to share here is the particular genius that is the oil and gas industry, and the way that that genius is put on display in this awesome institution.

I owe a lot to the Petroleum Museum. When I began my tenure as editor of this magazine 14 years ago, I did know a little about O&G, having been the son of a drilling engineer, but I possessed no hands-on knowledge. So much about the drilling process, for instance, mystified me. But I sensed that if I could grasp the rudiments of it—the early, primitive approaches and equipment—I had a better chance of comprehending the super-sophisticated, complex manifestations that we see today. It’s in the early phases of anything that its bare-bones functionality can best be observed.

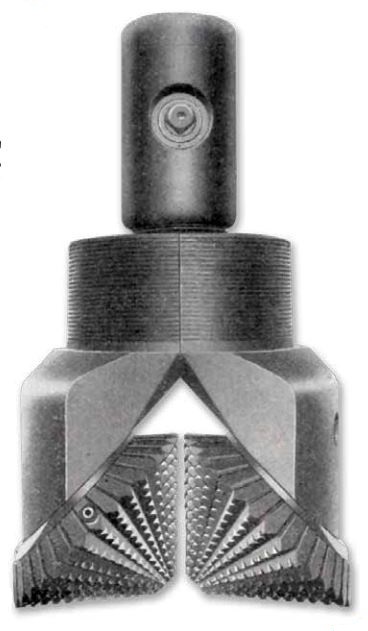

I remember, nearly 14 years ago, standing in front of the museum’s exhibit that shows the evolution of the drill bit. Part of that exhibit can be seen on our cover photo. There were two things I wanted to know. One, how do the teeth on a drill bit rotate to grind rock far below the surface? What powers those teeth to do the grinding action? Was there a localized motor inside the bit? Now, by contrast, I understood how a fishtail bit worked. It simply turned with the turning of the drillstring, scraping away just as someone might use a flathead screwdriver to get dirt out of a hollow rod. No localized motor was needed for a fishtail bit—all the force was applied up at the surface, on the drilling platform, turning the drillstring. But conical, meshed bits were not like that. They had an action to them—they weren’t a rigid blade on the end of a shaft. They rotated at the bottom of the drillstring, in a motion different from, or in addition to, the revolutions of the drill pipe.

The longer I gazed on those vintage drill bits on the wall, the more the answer emerged. It’s in the orientation of the cones. They are each canted at just such an angle that the teeth, at the widest points of their orbits, would come in contact with the rock wall of the borehole. Let’s remember that this is a rotary rig. The drillstring is revolving—turning to the right. Where these teeth meet the rock wall, the rock exerts a tangential force on the cones, causing them to spin (rotate), grinding the rock below the drill bit. No localized motor needed. And because the cones are enmeshed, one with another, they self-clean each other.

Voila! A light flipped on in my dim, dense brain.

The other question I had was, how is drilling mud circulated through a wellbore? I wrongly pictured the drilling mud, from ground level, being funneled into the space just outside the drillstring—between the drillstring and the rock wall of the wellbore. I knew that that space had room to hold mud, but I couldn’t picture how or why mud thus injected could circulate and thereby flush cuttings out of the well and cool the bit. Why would it flow back up?

While I studied those old drill bits, I again noticed something. Just above the point where the rolling cones intermesh, I saw a hole, or even more than one hole. And it hit me. Yes, of course! Drilling mud flows downward out of that hole (I learned it’s called a nozzle), out of the interior of the drill pipe, and into the space where the cones are grinding the rock. Before that moment, I had never conceived that the mud is pumped down through the hollow of the drill pipe itself. Then it squeezes out in the vicinity of the drill bit’s teeth, and from there it is forced out of the hole and up—but this trip back up is made outside of the drill pipe, through that area called the annulus.

And suddenly, it was all clear. And genius as well.

Multiply these two small examples of creativity and imagination against the tens of thousands of square feet of exhibition space and hundreds of displays in the Permian Basin Petroleum Museum, and you begin to get a picture of how this museum crafts a narrative of human innovation and ingenuity. PBPM is more than a tribute to oil and gas. It is a celebration of the human spirit.

Jesse Mullins is editor of Permian Basin Oil and Gas Magazine.