Click here to listen to the Audio verison of this story!

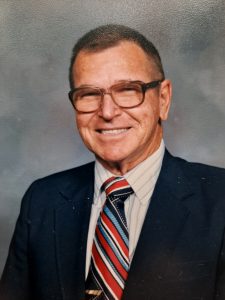

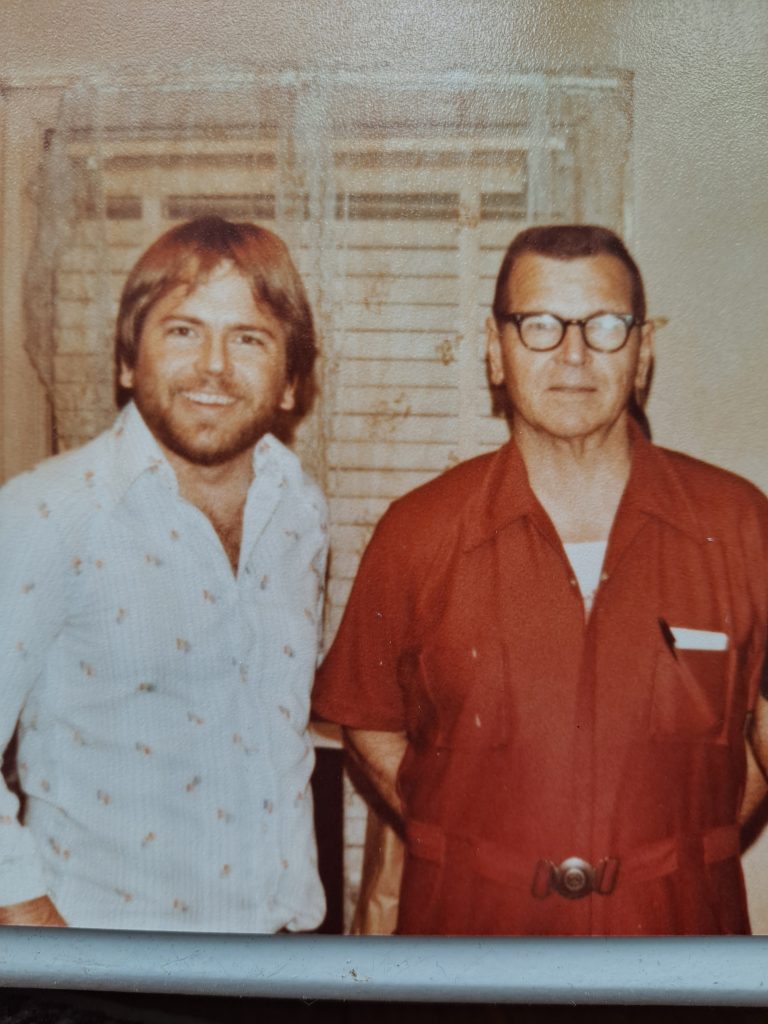

This month being the month that holds Father’s Day (June 15), I’m going to share a story of a father. It just happens that the story I know best is the one I know from my own dad, Jess Mullins, Sr.

He’s been gone now for 12 years. I think I speak for most of the men reading this when I say that he taught me, and modeled for me, the things that, over my life, have mattered most. I could lump these things under “God, family, and country,” and that would be accurate, but it just doesn’t describe the fullness of my dad, just as it wouldn’t describe the fullness of yours.

When we buried him in 2013, in Oklahoma, one of the town’s leaders said to me, “Your dad was an honorable man.” Like so many of his generation, widely acclaimed as the Greatest Generation, he lived by deep convictions and principles. I remember how sad the church members at his church were—and this despite the fact that he lived to age 89, with dementia coming on, and had lived past his ability to teach or lead there any more. No matter—they were concerned even then about the fate of their congregation, the prospects for it, with him no longer there. I was stunned. And ever since I have desired to be someone whose absence could mean that much.

Jess Mullins, Sr., spent his entire working career as a drilling engineer for Texaco, Inc. That career took him and his family from Illinois (the Salem field) to Kansas and to Oklahoma. Then overseas, as so many Texaco employees were sent. To Equador. Then to Maritius, in the Indian Ocean. Then finally to Illinois again, to lead a tertiary (CO2 injection) project. He was then the last Texaco employee left on their payroll who had worked in that Salem boom.

He never talked a great deal about his work. Shortly before his death, I was with him in the oil country of Oklahoma that he knew so well, and I asked him a question about drilling. I don’t recall that question or that answer, but I recall what he said next. Thinking back over his career, he mentioned something that must have really stayed with him. He said, “In drilling a well, what you really have to watch for [this was speaking as an engineer] is the ‘marker zone.’”

He was referring to the business of getting a core sample from the well. During the drilling process, drill cuttings were floated up by the drilling mud. These were sifted out and came to my dad in the form of sample bags. I well remember those sample bags. Much of the time, the back floorboard of his company car was piled up with those little cloth drawstring bags, each holding a little pouch of drill cuttings. I had never really known what he was looking for in those drill cuttings that he studied so much, but now, hearing from him about “marker zones,” it began to make sense.

“The marker zone,” he said, “is the zone just above the payzone. You’ve got to be looking for that marker zone, because when you find that, that’s when you need to be ready to pull out of the hole and put the coring bit on the drill string.” He paused. “Texaco would not have been happy if I missed my marker zone,” he said with a smile.

Jess Mullins grew up in Tulsa, Okla., the son of a refinery worker. As a teenager, in a home where the parents owned a car, he was given a Sunday task of picking up, and delivering to church, a family, or more than one, who had no wheels to get there. One of those families included the young Clara Ann Fowler, later to become known as the chart-topping vocalist Patti Page. Dad’s younger brother Ralph Mullins also had a stellar musical career—one that earned him a Wikipedia page. His brother C.L., whom I have written about before in this space, was a war hero. In those days, there were giants in the land. The Greatest Generation came by its name honestly.

Jess Mullins served in the U.S. Army in World War II. In adult, married life, he raised a severely handicapped, mentally and physically, son (deceased in 2024).

He was strict. He was frugal. Like so many of his generation—all Depression-era youths—he had conflicting traits, and sometimes they could be amusing to those who knew him. For one thing, he held competence in high regard, and always expected to encounter it. Any worker, any clerk, was to him an expert on that business’s offerings. That led to the conflicting trait, which was that he wanted, as a shopper, to get store goods at the lowest possible price. Thus, when discount stores and made-in-China goods (which were inexpensive, and thus quite appealing to my dad) became the norm, Dad never quit thinking that store clerks were knowledgeable in every aspect of their store’s wares. Thus, we would find ourselves at a Walmart—my dad’s favorite store—and he would be wanting to seek out floor help to get advice on the use of a particular piece of hardware.

“Dad, it’s going to be a teenager,” I would say. “Or a young man or young woman. And they won’t know what you’re talking about.”

Finding floor help was not easy in Walmarts, and I would always be right—the worker did not have Dad’s answer—but still, Dad never lost faith that any employee would know everything about their wares. “That’s their job,” he would say with emphasis. Every time.

He raised us to be dutiful and diligent. We worked but we also experienced the best that our world offered. We hunted. We fished. As a family, we did road trips all over the American West, and even into Canada. No one loved, nor knew more about, the history of the American West than my dad. I visited more historical sites—and we stopped at more highway markers—and I stood at more graves—than maybe anyone else of my generation.

Most of all, he raised us to heed our Maker. For that, I am more glad than for all of the other influences, as rich as they were. And are.

Happy Father’s Day to you in Heaven, Dad. You didn’t miss your marker zone.

Jesse Mullins, editor of Permian Basin Oil and Gas Magazine, can’t help but believe that an emphasis on God, family, and country is good for any generation of Americans.