By Steve Hendrickson

If you’re like me, you probably feel that the volatility of oil prices has been very high in the past couple of years. After all, oil prices were well above $100/bbl recently and had a negative price scarcely two years ago. And we’re experiencing significant global events that have an economic impact that influences oil prices, particularly the COVID pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

I began to wonder, however, if other forces might be at play that will lead to persistently higher oil price volatility even after the influence of these events passes. Specifically, it occurred to me that the United States’ re-emergence as a major oil producer could introduce more volatility since we don’t coordinate our output with our large producers to “stabilize” the market. And, since our production is heavily dependent on unconventional wells that produce at high initial rates and decline rapidly that they introduce the prospect of more rapid swings in supply that could move prices more quickly.

In his 2015 paper, titled “The New Economics of Oil”, Spencer Dale addressed this second concept. He concluded that unconventional oil should act as a “shock absorber” for oil supply because it could quickly respond to price signals. He noted, however, that much U.S. unconventional oil drilling is conducted by independent producers that tend to be more reliant on external sources of capital, and if this capital was not available, the supply response to high prices might not materialize quickly. We may be seeing that effect now. As noted in our commentary a few weeks ago (v2022-08), the oil-directed rig count has not responded nearly as much as it did during recent similar price spikes.

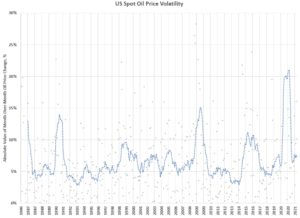

The accompanying graph charts oil price volatility over the last few decades. For this analysis, I used the monthly spot oil prices reported by the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) and calculated the absolute value of the month-over-month percentage change. A 12-month moving average is also shown.

There’s a lot of noise in the graph but looking at the moving average may lead to some meaningful observations. First, volatility is volatile; we seem to experience episodes of increased volatility and we’re in one now. Secondly, it appears that the trend of volatility was downward from about 1999 to 2014. Since then, the trend appears to be upward, but it’s hard to pound the table about that.

I think the factors I mentioned earlier, plus the greater connectedness of our economies and the flow of information will lead to more rapid price swings as events in one part of the world are more quickly felt elsewhere. And if that opinion holds, it has implications for U.S. producers’ investment and hedging decisions.

About The Expert

Steve Hendrickson is President of Ralph E. Davis Associates (RED), an Opportune LLP company. Steve has over 35 years of professional leadership experience in the energy industry with a proven track record of adding value through acquisitions, development, and operations. Before joining Opportune, Steve was Principal of Hendrickson Engineering LLC, a licensed petroleum engineering firm focused on reserves assessment and property valuation supporting property acquisitions and divestitures. Steve began his career at Shell Oil as an engineer in Permian Basin waterfloods and CO2 floods. After 16 years at Shell, he focused on leading upstream oil and gas reserves evaluation/engineering projects serving in management or as an executive at several E&P companies, including El Paso Production Company, Montierra Minerals & Production LP and Eagle Rock Energy Partners LP. Steve is a licensed professional engineer in the state of Texas and holds an M.S. in Finance from the University of Houston and a B.S. in Chemical Engineering from The University of Texas at Austin. He recently served as a board member of the Society of Petroleum Evaluation Engineers (SPEE) and is a registered FINRA representative.