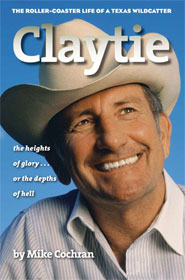

It is with sadness that we report the recent passing of the highly accomplished and much-revered West Texas oilman Clayton Williams. As a remembrance of his life, we share once again this personality profile we published some years ago. Our condolences go to his family and many friends.

“You can’t help but enjoy life when you are around Claytie.”

The woman speaking these words, Nancy Carpenter, should know—she’s worked for Clayton Williams for 38 years.

And while that’s impressive in itself, longevity in the Williams organization is not such a rare thing. Williams himself says he is pleased that he has had so many employees work for him for an extended number of years. “Last year we had a barbecue and I celebrated 47 people out of 250 that had been with me over 20 years. I am proud of that.”

And while that’s impressive in itself, longevity in the Williams organization is not such a rare thing. Williams himself says he is pleased that he has had so many employees work for him for an extended number of years. “Last year we had a barbecue and I celebrated 47 people out of 250 that had been with me over 20 years. I am proud of that.”

Sitting in his third-floor office June 14 in Midland’s lavish ClayDestra Center, Clayton Williams, legendary West Texas oil man, rancher, real estate mogul, philanthropist, and former Republican nominee for Governor of Texas, accompanied by a staff member and a family member, spoke with PBOG Magazine about the current operations of Clayton Williams Energy and his own career. He credits his organization and its human element for the still-unfolding successes they have enjoyed.

For his own part, he admits he is “pretty good with people.”

“I sold life insurance when I got out of the Army,” he says. “Insurance—that’s people. I like people. That’s why I ran for governor. But they didn’t like me quite enough.” (laughter.)

Williams is well known for his wit and his self-deprecating humor. It was his candor and his readiness to crack jokes that got him into trouble in his 1990 gubernatorial campaign, but, ever the philosophical type, he has often turned even that experience into a crowd-pleasing wisecrack or two.

Clayton Williams Energy, Inc., one of the three biggest Permian-based independent oil and gas exploration companies (alongside Pioneer Natural Resources and Concho Resources) operates primarily in Texas, New Mexico, and Louisiana. As of year-end 2011, its estimated proven reserves were 64.3 MMBOE, of which 61 percent were proved developed. Some 77 percent of the company’s reserves are in oil. In 2011, the company added proved reserves of 20.9 MMBOE through the drill bit, resulting in a reserve replacement of 384 percent. CWEI is traded publicly on the Nasdaq Exchange.

On the day we’re speaking, Clayton Williams Energy is operating 14 rigs, with four active in Reeves County (Delaware Basin), three in Andrews County (Wolfberry), one in the East Permian Basin, four contracted out to third parties, and two being refurbished in an Odessa yard. The numbers and locations can shift weekly. It’s constantly in a state of flux.

The company’s wholly owned drilling subsidiary, Desta Drilling, employs 275, and another 230 work for parent company Clayton Williams Energy.

“I’ve formed several companies,” Williams says. “My best company, in many ways, was Clayjon Gas Company. At one point, when I sold it in 1988 [for $220 million], it was the second-largest individually owned gas company in the state—second only to George Mitchell. I’ve continued my true love, though, which has been exploration. Oil and gas drilling and development. That’s basically where we are today.

He’s a diehard Aggie, and though he tells Aggie jokes, he is the first to say that  A&M gave him a good education. His degree was in agriculture but, as he says, he “has been fairly comfortable at doing other things.”

A&M gave him a good education. His degree was in agriculture but, as he says, he “has been fairly comfortable at doing other things.”

That’s an understatement. Few have been more daring or more successful outside their established field. At one time Williams went up against AT&T and the major telecommunications firms with his ClayDes Communications, which was short-lived (four years) but remarkably successful, given the climate then for telecommunications concerns. (“When we started, a long-distance call, by AT&T, was 44 cents a minute. When I sold it, it was 17 cents a minute. But I made a little money because we expanded well. Today the cost is, like, a penny a minute—virtually nothing. So I got out by the hair of my chinny chin chin. [Laughter.] But it was interesting.”)

It’s been a run of ups and downs, with the ups outpacing the downs. “At one point in my career I think I owed pretty close to a billion dollars,” Williams says. But the man who has made a mantra of “OPM—Other People’s Money—has made good on his borrowings. “I knew what I was doing,” Williams says of the sometimes-colossal debt burden. “All the money I borrowed, it wasn’t risk free, but it was in my own businesses. I wasn’t investing in someone else’s business. I was putting the money in what I did.”

So maybe to OPM we could add IIY. Invest In Yourself.

Growth has done a lot to change how he operates, too. “When I started in 1954—that was, what, 58 years ago?–no technology existed for horizontal drilling, deeper drilling, large fracs, and so forth. Then, too, when I started I didn’t have but about $2,000 in bank credit. I’ve [since] had that up to about $700 million. So you’re operating one way when you don’t have any money or credit, and then eventually you get income [an income stream] and so forth and, well, then it’s a totally different ball game.” He paused. “It’s like… I’ve been in four or five different businesses but they’re all the same one.”

His principal field of operations these days is Reeves County—in the Wolfbone play. “Four or five years ago I was more in the Wolfberry, in Andrews County. I’ve been in the Austin Chalk / Eagle Ford since 1974. I’ve had plays in most of the country. I’ve had an office in Denver, Oklahoma City, Houston… I’ve been in each of them to a larger or lesser extent. And what it all boils down to is that I have done better at home in Texas.”

His principal field of operations these days is Reeves County—in the Wolfbone play. “Four or five years ago I was more in the Wolfberry, in Andrews County. I’ve been in the Austin Chalk / Eagle Ford since 1974. I’ve had plays in most of the country. I’ve had an office in Denver, Oklahoma City, Houston… I’ve been in each of them to a larger or lesser extent. And what it all boils down to is that I have done better at home in Texas.”

They’ve drilled 800 wells in the Austin Chalk, and below the Austin Chalk formation lies the Eagle Ford. “So it looks like we are going to drill all of that,” Williams says, and he has suggested previously that he might have hundreds of wells to drill there in his own current leases. “So we’ll drill it again—maybe all of what we’ve drilled before—but it will be in a deeper zone, in the Eagle Ford. That’s very normal in the oil business. You drill shallow and hold the acreage, and then later on something deeper happens and you drill deeper. That’s happened to me in Andrews County, now. It’s been common in our industry that the majors would drill the shallow stuff and hold the acreage by production. Frequently there are three or four plays in an oil field. In the Austin Chalk, it looks like there will be two and, in some spots, three different pays.

Just as Henry Resources is known locally for its perfecting of the vertically drilled well, so has Clayton Williams been known for its horizontal drilling. Williams was into the lateral activity early, and even decades ago was drilling some of record-setting horizontal wells. He explained the difference between his horizontal work and Henry’s vertical as the difference in the rock that someone is exploring. “I’m drilling horizontal where there is only one pay,” he said. “In the Austin Chalk, and in Reeves County, it’s the Wolfbone. In Andrews County, I’ve got several pays, so I am drilling vertical. The Wolfbone—that’s where Jim Henry and I are into similar stuff. So we are doing the same thing there.”

Just as Henry Resources is known locally for its perfecting of the vertically drilled well, so has Clayton Williams been known for its horizontal drilling. Williams was into the lateral activity early, and even decades ago was drilling some of record-setting horizontal wells. He explained the difference between his horizontal work and Henry’s vertical as the difference in the rock that someone is exploring. “I’m drilling horizontal where there is only one pay,” he said. “In the Austin Chalk, and in Reeves County, it’s the Wolfbone. In Andrews County, I’ve got several pays, so I am drilling vertical. The Wolfbone—that’s where Jim Henry and I are into similar stuff. So we are doing the same thing there.”

But all the talk about “multiple pay zones” and “stacked pay zones”—sometimes bandied about as the salvation of the industry—does not faze Williams. “Let me say this about pay,” he offered. “None of the pay is worth a damn. It is so sorry you have to frac the hell out of it. Where there are eight pays, we don’t do horizontal. We perforate and frac each of the pay zones. And that’s because you have a lot of pay, vertically. Where I am at in Reeves County, where I am at in the Austin Chalk, yeah, vertical is where the pay is. So you might be 4,000 feet deep in the Wolfbone, but you might be 5,000 feet horizontal, and you’re fracking each of those.

“And if it doesn’t make money, it doesn’t matter.”

Tom Scott, an attorney of long acquaintance with Williams, says that Claytie has “all the best traits of an oil and gas finder.”

Williams is dynamic, Scott says. “He’s willing to hire and encourage good  employees and rely on their judgment. He fairly rewards their services and he expects loyalty from his employees. He wants the best talent. He has it himself.

employees and rely on their judgment. He fairly rewards their services and he expects loyalty from his employees. He wants the best talent. He has it himself.

“He’s plainspoken. A West Texan. Not a schmoozer. Not a politician—and that’s what’s gotten him into trouble—speaking his mind. He’s not going to butter up others.

On the job, Williams is “a promoter of geology and everything about it,” says Scott, who is a principal in the Midland-based partnership of Bullock and Scott. “His father was an engineer. His whole family has been oriented around the legend of his grandfather [O.W. Williams], who was a pioneer lawyer and surveyor out in West Texas. O.W. surveyed the townsite of Lubbock. He was a writer also, and he described things such as a buffalo stampede of the time.”

“Clayton has benefited from the family he had, but he has also picked it up and gone straight forward with it,” Scott says. “He is someone who knows how to put an organization together and keep them together.”

Clayton Williams staffer Nancy Carpenter, who works at Williams’ farm and ranch operation in Fort Stockton, says that her boss’s work ethic is what impressed her the most, initially, about the man

“He’s just such an upbeat person and so positive,” she says. “He’s really the definition of a wildcatter because he’s not afraid to take chances. He’s an adventuresome guy and his love is reaching out, branching out, and trying new ventures. Or new drilling prospects. His success in the oil business has supported his love of the farm and of ranching. There’s not that much money in farming—the profit margin is low—but he also stays active here because his hometown is Fort Stockton. And I have admired him for that.

“In the ’80s, in that oil bust, he had to fend off bankruptcy, and to do it he sold off Clayjon Gas to pay his debts. I think God honors that. He went on to become successful again. He is a wealthy man but unlike a lot of wealthy people he controls his money—he does not let the money control him. He is generous with his money. He has done much for our town and the people of Fort Stockton. He helps with scholarships throughout his company. He feels so strongly about getting an education.”

Summing up, she added: “Everything he does, he enjoys. He is amazing. He makes you have fun when you are around him.”

Asked what it takes to succeed in this business, Williams doesn’t hesitate.

“Honest and integrity. That’s an easy one. Who wants to deal with a crook? So much of our industry is inter-related dealing. I borrow money from banks. They have to believe I am going to pay them back. I have employees who need to believe that they are going to be treated fairly. I think that is true across the board. Honesty and integrity is the key.

“Honest and integrity. That’s an easy one. Who wants to deal with a crook? So much of our industry is inter-related dealing. I borrow money from banks. They have to believe I am going to pay them back. I have employees who need to believe that they are going to be treated fairly. I think that is true across the board. Honesty and integrity is the key.

Asked if the oil patch is a place where “the good drives out the bad,” Williams is inclined to agree.

“There’s a little bit of the Code of the West,” he says. “Out here, there is the pioneer feeling, too—it’s in a lot of ranch people. But in the oil business, I think it is everywhere. Word gets around pretty fast whether you are a crook or not. You’ll find a high percentage of honesty and integrity in the oil and gas business, and right behind it is the cattle business. So there are some ties. The [early] oil men leased from landowners, which were the early ranchers, so that created a community effect between the two.”

Asked about family, Williams says what is already well known—that it is very  important to him. Modesta, his wife of 47 years, is his attractive (a former model) and highly accomplished mate. “I have a wonderful wife,” Clayton says. “She is good looking and she must not have good eyesight or she would have kicked me out a long time ago. We have five kids. Family is very important to both of us.

important to him. Modesta, his wife of 47 years, is his attractive (a former model) and highly accomplished mate. “I have a wonderful wife,” Clayton says. “She is good looking and she must not have good eyesight or she would have kicked me out a long time ago. We have five kids. Family is very important to both of us.

“And, in that connection, so are my employees. My employees are my family as well.”