The Making of a Resource

by Jesse Mullins

In Part One of this series, we examined some of the distortions used against oil and gas by not just hostile activist groups but by media, even mainstream media. In Part Two, we broadened the perspective by raising the issue of morals—the morals of our side. In this concluding installment, we delve deeper into that vein, asking some questions that should have been asked long ago, and providing some answers to same.

Since the mid-20th Century, the oil and gas industry has been a political pariah, blasted regularly by critics with a need for a capitalist endeavor to villify for political purposes. Because it deals in extraction and heavy industry, oil and gas makes the perfect foil for forces looking to score points by taking a moral high ground against purported “polluters” and “exploiters.” Never mind that those same critics live lives of ease made possible by oil and gas. It’s a hypocrite’s game, and some can play it to a T.

But there’s hope for our side—hope that the tide could turn—as a new generation of Americans questions the prevailing propaganda hurled at our industry. Questions, yes, and finds large holes to explore.

In our last installment of this series, we sounded a new note—what one author has called “the moral case for fossil fuels”—and in this concluding article we expand upon that angle, with comments from its prime proponent. This “morals” dimension might well be the most foundational defense our industry could consider.

Practical philosopher Alex Epstein is that proponent, and his fresh new book The Moral Case for Fossil Fuels is at once startlingly original and yet solidly grounded in logic and common sense.

And we share, again, from two journalists whose film works have touched off innumerable conversations about how oil and gas have been unfairly stigmatized and demonized by less-than-honest adversaries.

Those journalists—documentary filmmakers Phelim McAleer (FrackNation) and Mark Mathis (spOILed and the planned project Fractured)—have exposed a great deal about what’s wrong with critics of the oil and gas industry and what’s right about the industry itself.

When we left off in Part 2, Epstein was saying that oil and gas kept on the defensive because the environmentalists have framed the debate. More about that shortly. But for now, to recap our case thus far—Alex Epstein ventured three basic ideas that, if they are accepted by his listeners, will generally bring those listeners around to his thinking.

If we might quote ourselves from Part 2 of this series, here is how Epstein makes his three points:

“One, there is the idea that we should be ‘big picture’ in our thinking. We need to look at all the benefits and all the risks, and we need to look at them carefully. We need to consider their magnitudes carefully. Anyone will agree with that. If we look at the discussion, 99 percent of the discussion of this issue is not big picture…. We’re usually just looking at all the risks…. [The second] idea is that we have to be clear about our goal or our standard of value. What do we regard as good, for terms of deciding what is moral? The right one is to be concerned with human life above all. So, whatever discussion we’re having, if we’re saying something is good or bad, that ultimately has to connect to maximizing human well-being. If we’re talking about climate, the question is not ‘Do we affect climate?’ but rather the question of the overall effect of using fossil fuels—and that ‘overall effect’ includes any effects on climate—is that overall effect positive or negative? Once we frame it that way, that turns out to be the most important method to follow. The other idea I talk about is how to use experts. You don’t use experts as authorities that you bow down to. You use them as advisors that explain things to you. If you can get those three rules—big picture, maximizing human well being, and consulting experts as advisors, then everything changes, because now we’ve set the table stakes.”

But that’s not been the grounds for discussion, where conversations about oil and gas are concerned.

“The environmentalists have basically framed the debate,” Epstein says. “I believe that most people in the industry [have bought into it], certainly, but even commentators have bought into their framing of it.”

Fresh Ground

Epstein is emphatic that taking the right approach to the bigger picture will yield an outlook that is dramatically more favorable to fossil fuels that what the average person holds.

“If, in your mind, you can follow those three rules, you’ll come to the conclusion that fossil fuel use is overwhelmingly beneficial, and that if we hold the debate to those rules, then that conclusion will emerge in the debate,” he said. “Part of assessing the bigger picture is looking at the risks and benefits of the alternatives. So you can look at both, you look at the reasons why we choose to use coal instead of wind, and you see that if we tried to rely on wind in the way we rely on coal energy, our lives would be very bad.”

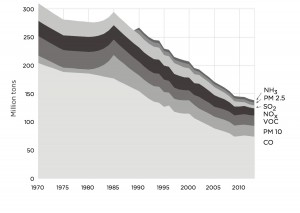

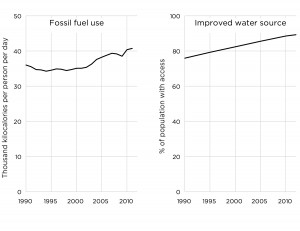

As fossil fuel use has increased, life expectancy has increased, Epstein said.

“They’re correlated for a reason. So, length of life and quality of life are both impacted. Somebody might want to say, ‘Well, oil and gas producers are polluters and that is detrimental to health.’ But there is a vastly greater detriment to health to not have fossil fuels.”

Epstein turns conventional thinking on its head with his next assertion.

“We’re thought to think of nature as giving us a stockpile of resources that we then deplete, and therefore, every act of consumption is an act of future destruction,” he said. “This is obviously not true, because otherwise the caveman would have had way more resources than we do, instead of incomparably fewer resources than we do. So there’s an important distinction between raw materials and resources. Raw materials are not resources until we, using our intelligence, transform them into resources.”

Asked if he could give an example, he offered the following:

“All the fossil fuels are examples of this, because they were not resources before [human beings] made them useful, but one example from outside the industry is aluminum, which is one of the most plentiful mineral elements in the Earth’s crust. Yet, several hundred years ago it was completely useless because we didn’t have the technology to transform it into this amazing metal. Once you can turn the raw material into the resource, then they can say, ‘You’re depleting the resource.’ But there was no resource. You’re creating the resource.”

The process gets carried a step further when we turn to the idea of shale technology.

“Yes, shale was a non-resource, and we turned it into a resource,” Epstein said. “So it’s erroneous to say we’re resource-poor when the resource didn’t exist until we made it. Nature is resource poor in the sense it doesn’t give us many resources. That’s why, historically, we’re poor.

“We’re taught to think that the planet is perfect before we get there, and we ruin it, and therefore the goal should be to save the planet from human beings, versus the view that the planet, by the standard of human well-being, is wildly imperfect, and we need to improve the planet for humans. This view would be much more common sense for anyone who actually had to live in nature. But if you’ve only lived in the industrial world, which is a radically improved human environment, and then watched Disney movies, you have this view that nature is perfect, idyllic, and friendly. Then you somehow had the idea that the polar bears are our best friend and crucial ally, and we should be willing to sacrifice our civilization so that those populations may grow.”

A Tool for Transformation

Yeah. The form factor is just the form that information takes. It’s just that I’d like a book as a form factor because they’re easy and cheap to distribute and because if a person consumes it, they’ll learn a lot. Now, I like … Companies often tend to think terms of very, very short things, which are good, but I view those as those are good ways of getting attention but they’re not tools of education or transformation.

The biggest validation I’ve got is when people who had a negative opinion on fossil fuels write me and tell me that they now have a positive opinion. I think there’s … This book was written to do exactly that. It’s gratifying when that happens and I get it a lot. There’s lots of other kinds of recognition, which are nice.

Mathis, for one, told PBOG that the industry itself has not awakened to the fact that if it doesn’t defend itself, things are not going to get better.

“They’re just going to get worse,” he said. “They are hoping that it’s not as I’ve described it [in his film and in his previous remarks in PBOG]. It’s not their way of doing business. It [defending themselves against attacks] is not what they think about. And so they’re reluctant to get involved. They worry about blowback. So they don’t really do anything. They sit back. And this really cuts to the core of what my next film line, called Fractured, is about: that the industry itself is highly fractured. It’s not really one industry. You’ve got refining, pipelines, retail, exploration. There’s all these different segments of the industry and they don’t unite.

“It’s hard enough to get the producers, let’s say, to speak with a forceful voice publicly because they’re not unified either—because you’ve got major producers, mid-major producers, little producers, and they don’t all have the same interests. Many of the things that the majors are okay with, the little guys are not, so there’s this tension even within one sector of the overall umbrella of the oil and gas industry. There just isn’t any kind of coordinated effort to say, ‘You know what? We’re going to have to fight back, and if we’re going to fight back, the only way for it to be effective is we’re all going to have to start speaking up, and the attack groups and their attackers wouldn’t be able to manage it if you had many companies and trade groups speaking out forcefully.’ Then what do they do? It would be very hard for them to handle that, but it’s going to take a coordinated effort and… I don’t know, I don’t know how that happens.”

Or maybe he does, because Mathis comes right back with this:

“You start with a fervent committed base and you move outward from there,” he says. “Your core is the industry itself, the people who are employed by the industry. It’s their livelihood. Then the concentric circle out from that is people who are indirectly connected. Maybe they have a job. They’re not working the industry, but the industry is a big part of what they do. Maybe you live in Midland, but you don’t work in the oil business. Then you move out from there, and now you’re starting to get, circle by circle, closer to a neutral audience and then you move out, out, out.

“The farthest circle out is the people who are committed against you, but you’re never going to get those people, and you shouldn’t even try. I don’t have any illusions or delusions about trying to persuade a person who is passionately anti-oil and anti-gas or -coal. They’re not objective. They couldn’t receive it. You build it from the inside out, and what the industry doesn’t know that the environmental activist community knows is this very phenomena. There are half-a-dozen movies out right now that have been produced since Gasland and Gasland 2. Just even in the last 18 months. A half a dozen anti-oil and -gas movies.”

Mathis said these movies are being shown in localities where activists are trying to stop the industry through stopping hydraulic fracturing. “Ultimately, they want drilling stopped, but the mechanism that they’re using to make that happen is just to create some irrational hysteria around the technology that sounds bad: fracturing. That’s just a tool, but they’re using it. They spend a lot of time and energy focusing on informing and inspiring their base. Along the way, they’re effective at picking up a compliant press. They get their message out that way. They’ve got politicians who are ‘paid for’ and they get their message out that way, too.

He added: “They’ve got actors and other people who have different reasons for getting involved in these discussions, so they reach those people as well, because they’re more effective at reaching out to a general audience. Those avenues aren’t really open to the industry, but the industry… Well, here’s the wake-up call to the industry: You need to spend a whole heck of a lot more time informing and inspiring your own people.”

Evidence Can Be Had

A recurring theme in Phelim McAleer’s film FrackNation is the idea—and why it’s not glaringly apparent to more people is just amazing—that truth can be obtained, claims can be verified (or debunked), information can be gathered, answers can be found. McAleer does just that in FrackNation, and his findings, and his assertions, are markedly in contrast to the allegations hurled by the anti-industry set.

“There’s actually a ways of finding out the truth of that matter,” McAleer said. “You can say to that person who is alleging that their water is polluted, ‘Do you have independent scientific evidence to back that up?’ If they don’t, then the truth is your water is not polluted. Or you can ask them, ‘Have you made any claims before that have been proven to be wrong?’ If they have, then you say, ‘You’ve no credibility.’ We need to look skeptically at that. Journalists seem to have lost their skepticism.”

McAleer gives an example from his film. “There’s a guy in our movie named Craig Sautner. He’s the guy who says, ‘There are three types of uranium in my water, two of them weapons grade.” Two of them weapons grade. Most ordinary people, when they hear that, they laugh. All these journalists heard that and ran it as a true story. He was around the world, that story was around the world, and he hadn’t one iota of evidence, and common sense would tell you it’s nonsense, but there are these journalists who say, ‘I just want the audience to make up their own mind.’ Well, no, actually, you can actually ask them for evidence there. That’s a very simple case. Where’s the evidence? Where’s your scientific report to back that up? Oh, you don’t have one? Well, then that means you have no credibility and I need to let my audience know that.”