In Tune with Their Place and Time

by Joe W. Specht

Larry Gatlin and the Gatlin Brothers—Steve and Rudy—enjoyed a string of hits in the 1970s and 1980s, combining tight-knit three-part harmonies with what one observer labeled as a mix of “Las Vegas glitz with down-home appeal.” Larry, the primary wordsmith for the group, also garnered a Grammy Award, in addition to receiving three awards from the Academy of Country Music. Just as importantly, the brothers’ oil patch roots run deep. Their father, William Wayne “Curley” Gatlin, was a roughneck, one who climbed the rig pecking order rung by rung eventually to become a driller; the brothers’ mother, Billie Christene Dolan Gatlin, also came from a family of oil field hands. Her father, Clib Dolan, celebrated his 72nd birthday on the job at a drilling site.

When Larry was born in 1948, his father was working for the Superior Oil Company in Andrews, Texas. Because Andrews didn’t have a hospital, Curley Gatlin drove his pregnant wife to nearby Seminole, 29 miles north of Andrews, in Gaines County. And while Seminole residents might not agree, Larry maintains in his autobiography, All the Gold in California and Other People, Places, & Things, “Seminole only has two real claims to fame: Larry Gatlin and Tanya Tucker were born there, at Seminole General Hospital.”

Curley Gatlin kept the family on the go following employment opportunities in the patch. In 1951, the year that Steve was born, the Gatlins changed residence eight times. Rudy was born the next year, and before moving to Abilene in 1953, the family lived in Olney, Ballinger, Post, Aspermont, and Snyder. Abilene, as Larry explained, was “the biggest town on [U.S. Highway 80] between Fort Worth and Odessa and as such was a good job market for a driller. Dad worked for several companies at different jobs. The work was steady, and we were finally putting down some roots.” Indeed, far from being “nomads by choice,” the Gatlins, like so many mobile oil field workers and their families, yearned for the chance to settle down in a two-bedroom house in a community such as Abilene.

Billie Gatlin’s parents placed a high value on music and “insisted” their daughter learn how to play the piano and read church music; she accompanied her father at singing conventions “long before she could reach the pedals.” Billie, in turn, imparted her passion for the music to her sons and daughter, LaDonna Gayle, born in Abilene in 1954. With the active support of their mother, who provided piano accompaniment, six-year-old Larry, three-year-old Steve, and two-year-old Rudy made their first publicized appearance on March 8, 1955, at the Rose Field House on the campus of Hardin-Simmons University to compete in the third annual Cavalcade of Talent Show.

Abilene Reporter-News staff writer Phyllis Nibling branded the brothers as “the three youngest hams in the show… perky as little sparrows.” She reported, “The three little Gatlin brothers won the audience over completely—in the juvenile division—with their nonchalant and gutsy singing of an old-time gospel song.” Nibling concluded, “In a couple of more years, the Gatlins may be booked as ‘Three Guys and a Gal.’ They have a 6 month old sister, [La]Donna Gail [sic], at home.”

The next month, on April 4, the boys, now billed as the Gatlin Trio, played to an audience of more than 5,000 attendees at the 63rd annual Jones County singing convention in Anson, where they were singled out as “one of the biggest hits of the convention.” Back in Abilene on May 8, the Trio was one of twelve featured acts at McMurry’s Radford Auditorium for a talent show to benefit the Taylor County Rehabilitation Center. They were also invited on stage for an impromptu sing-a-long at a concert headlined by the Blackwood Brothers and the Statesmen Quartet.

The youngsters quickly caught the attention of Slim Willet. In addition to hosting the Saturday night Big State Jamboree, which aired live on radio station KRBC (1470 AM) from Fair Park Auditorium, Willet also had his own weekly television show broadcast on KRBC-TV (Channel 9) on Wednesday evenings. Willet contacted Billie Gatlin to arrange for the Gatlin Trio to perform first on the Big State Jamboree and then on his television program. As Larry recollected, “Doing The Slim Willet [television] Show was a lot of fun… Back then the show was broadcast live, and if you flubbed up everyone knew it. Rudy, who was only two, was easily distracted. [He chased bugs in the studio] right in the middle of a song … It was a hoot.” The Gatlin Trio soon became regular members of Willet’s television cast. Years later, Larry put these early show business experiences in perspective: “… I’ve gone from Fair Park Auditorium to Carnegie Hall… from KRBC radio to the Tonight Show.”

Abilene’s proximity to petroleum production in West Central Texas, including the Scurry County field, convinced major oil companies—Conoco, Gulf, Humble, Magnolia, Texaco, and Sinclair—and independents alike to open regional offices there after World War II; supply houses soon followed. But by the mid-to-late 1950s, with the ongoing boom further west, these same companies began relocating to Midland, with Odessa serving as the principal operational base for labor and supply.

The exodus affected Curley Gatlin, too. “When the oil fields [around] Abilene played out,” Larry recalled, “and Dad was again out of work, he decided to pull up stakes and move us….” The day Curley Gatlin announced the move—Dec. 18, 1956—is a day Larry Gatlin declared as “Black Friday.” After a brief stay in Olney, the family headed for Odessa. “The next ten years would be the happiest of my life,” Larry said, “Odessa was not Abilene, but it was not Olney either—and that was good.”

In Odessa, the Gatlin Quartet (little sister LaDonna Gayle was now a member, just as Phyllis Nibling had predicted) began making a name for themselves singing at churches throughout West Texas and participating in singing conventions and talent contests. Mrs. Gatlin transported her brood to and from the out-of-town engagements; along the way, their paths crossed with an up-and-coming Roy Orbison and the Teen Kings. They connected with Calvin and Lou Wills of the Singing Wills Family, who also owned a record company, Sword & Shield (headquartered in Arlington, Texas), specializing in gospel music. The Gatlin Quartet recorded three albums for Sword & Shield: The Old Country Church (LPM 9009), I Shall Not Be Moved (LPM 9010), and Tenth Anniversary (LPM 9011). With Mrs. Gatlin behind the wheel of a 1962 Rambler station wagon pulling a U-Haul trailer with wardrobe, instruments, and equipment, the Gatlin Quartet ranged as far west as New Mexico, Arizona, and California. In 1964, they even sang at the World’s Fair in New York City.

All the while in Odessa, Curley Gatlin was commuting each day to various work sites. As the driller, he could also be called on to ferry the crew out and back. By this time, the state had responded to the need for easier access to the oil patch with better paved highways and graded all-weather roads. This made it possible for the crews to reside at a greater distance from the workplace. Still, as Larry bluntly put it, “Life really stinks when you have to drive 70 miles one way to get to a stinking oil rig in 100 degree heat or 10 degree cold for barely enough money to get by… Dad was tired. Physically. Emotionally. Spiritually exhausted all the time when I was a kid… But he kept keepin’ on because a man takes care of his family….”

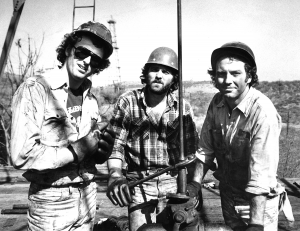

Since leaving West Texas behind, there has been occasion for Larry, Steve, and Rudy to salute their oil patch upbringing. On May 25, 1981, the ABC television network aired an hour long special, Larry Gatlin and the Gatlin Brothers Band, which followed their “musical wanderings” from the days of the Gatlin Trio. To honor three generations of the Gatlin family who “toiled as drilling rig workers,” one segment of the special, with footage shot at an East Los Angeles oil field to simulate similar conditions in Texas, featured the brothers wearing hard hats and working on the rig floor.

It wasn’t until 2009, however, that Larry turned his songwriting attention to sketching a slice of oil field life. He did so at the urging of Paris, Texas, and Nashville transplant Leslie Satcher, herself an accomplished wordsmith (Satcher’s list of credits include Gretchen Wilson’s “Politically Incorrect” and George Strait’s “Troubadour”). Gatlin described the collaboration: “Then my cheerleader, Leslie Satcher, sat down with her guitar and said, ‘Come on Larry Wayne, I’ve wanted to write a song with you since I was 18 years old… let’s do it right now.’ So we did ….” The song, “Black Gold”—slang for petroleum—is one of the highlights of Pilgrimage (Curb D2 79153), a follow-up to Gatlin’s 1974 album, The Pilgrim.

“Black Gold” is the story of a relationship torn apart by wind, dust, and isolation. And it brings to mind an earlier pre-World War II period when most oil field exploration took place in remote locations requiring workers and their families to live close by. The lyrics articulate a theme familiar to many wives who endeavored to adapt to life in the patch: how does one, while attempting to make a home for her family, come to terms with a harsh environment and a peripatetic husband intent on cashing in?

As the song amply makes clear, in arid West Texas, it was impossible for denizens to escape the constant assault of sand and dust. “Woke up with a mouthful of dust / Ol’ west wind the color of rust / Rolled across my bed.” In pre-air conditioning days, with windows open, it was not unusual to turn over in bed and find body outlines in sand on the sheets. A housewife living in Crane, Texas, explained how she dealt with the dust in their small house. “You just rearranged it,” she matter-of-factly admitted.

More significantly, the woman of the narrative “couldn’t take the being alone / She tried it but not for very long.” Before picking up and leaving, she is heard to declare, “This oil field just don’t feel like home.” As such, she is an example of those wives who “vowed to move on” when the uncertainty and tedium became too much to deal with. The nineteenth century pioneers on the Great Plains called it simply “loneliness.”

“Black Gold” also conveys the husband’s point of view. Undoubtedly one reason his wife decided to leave was because he has “worked six months without a break.” But he endures the long hours “just to get a piece of the pie.” He is more than aware, too, that “This ain’t my rig but what can I say / It’s mine ’til I move on and get one of my own.” With a little luck and a share of the action, a fella could truly capitalize. Curley Gatlin, according to Larry, had such an opportunity, but “a guy cheated him out of an interest in an oil well that would have made us rich for life.”

The chorus of “Black Gold” sums up the husband’s conviction that he will bring in a successful well on his own and, in so doing, get his wife back.

Black gold you drove my love away

Black gold so hard to find

Black gold I’ll be chasing you today

When I catch you maybe she’ll put

Her arms around this ol’ roughneck of mine

“Black Gold” also fits comfortably into the Gatlin Brothers’ song bag along with “All the Gold in California,” their 1979 number one hit. “Black Gold” became a regular part of the Gatlins’ concert repertoire, and they even spotlighted the song on January 28, 2011, on Craig Ferguson’s CBS television Late Late Show. In front of a national viewing audience, Larry offered testimony yet again to his West Texas oil patch roots: “My personal pilgrimage began in the great state of Texas. As a little boy, I watched my father chase that oil rig across that great state. I’ll never forget the smell of oil and the sight of dirt whipping across the Texas plains. And I’ll never forget that black gold.”

[Editor’s Note: Neighbors, this concludes this fine and poignant tribute to the music of the Permian Basin oil patch. It’s a story that has had it all—triumph, tragedy, achievement, pain, beauty, humor, brilliance, and honor. We hope you enjoyed it. If you want to delve deeper into this rich and vital narrative, just note the project that is descibed below. Our thanks to you for following along, and our thanks to talented author Joe Specht for caring enough to preserve this cultural heirloom.]

Joe W. Specht is at work on Smell That Sweet Perfume: Oil Patch Songs on Record, a project focusing on commercially recorded songs with petroleum-related themes as sung/written by performers with roots in the Gulf-Southwest. If you have a song that fits, contact him at jspecht@mcm.edu.