by Joe W. Specht

Oil Patch Songs from the Permian Basin

Part 4 of 6

Andy Wilkinson and Charlie Robison, two sons of the West, are troubadours of the West Texas mystique as well.

Twenty-one miles northwest of Odessa on the Kermit highway (Texas 302), and in the heart of the TXL oil field, is Notrees, Texas. As the story goes, the community got its name after the one indigenous sapling in the area had to be cut down during the construction of the Shell Oil gasoline plant in 1946. The same year, Charlie Brown, the owner of a small grocery store, received an appointment as postmaster. With the one tree gone, he decided Notrees was a most appropriate name for the post office. During its heyday in the 1950s and 1960s, when the population was reportedly 500, Notrees even had an elementary school that served workers’ families living in the nearby Shell company camps. In addition to the uniqueness of the name, Notrees has also been singled out for recognition in Andy Wilkinson’s “The Tumbleweed Christmas Tree.”

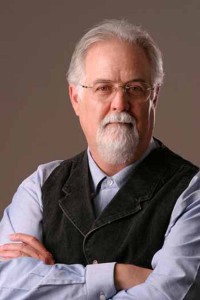

Andy Wilkinson was born in 1948 in Slaton, Texas, in the southeast corner of Lubbock County. He graduated from Lubbock’s Monterey High School and Texas Tech University and pursued a varied career as police office, commodities trader, and financial planner. Since 1991, Wilkinson has earned his livelihood as songwriter, singer, poet, playwright, and historian of the South Plains-Panhandle region, while receiving five National Western Heritage “Wrangler” Awards along the way; he is currently Artist in Residence at the Southwest Collection at Texas Tech University.

Recorded in 1990 at the Caldwell Studio in the Hub City, “The Tumbleweed Christmas Tree” features Wilkinson’s 12-string acoustic guitar, along with the multi-talents of Lloyd Maines on guitar, steel guitar, and bass and the harmony vocal of LaTronda Maines. Wilkinson included the song on his debut album, Texas When Texas Was Free (Adobe Records ADOB 1001), and subsequently on An Ordinary Christmas: A Celebration of Death and Rebirth (Grey Horse; reissued in 2009 by Yellowhouse Music), a collection that has become recognized as a seasonal classic since first released in 2000.

Wilkinson provides the background on how the song came about: “Cary Banks, who plays keyboards for the Maines Brothers, called to ask if I had written any Christmas songs. At the time [1989], I hadn’t. They’re usually too mushy and maudlin. I thought I’d write one about people who were too poor for Christmas… I thought the tumbleweed was a good symbol for not having enough money. The setting for the song was the West Texas oilfield town of Notrees.” Wilkinson’s father was a farmer, and Andy never had occasion to spend time in the oil patch; no matter, “The Tumbleweed Christmas Tree” has more than a scent of that sweet perfume.

It was a rough year for a rough-neck’s children,

Hard times, and harder livin’;

We moved when the rent come due, and it come due once a week.

Found us in an old house-trailer,

West of Odessa, near a town they call Notrees.

Too poor to pay attention,

Daddy lived on good intentions,

And he intended Christmas to be just what we believed.

Drove to town in the company pickup,

But when he didn’t have the saw-buck

For the price of a Christmas tree, he brought back a tumbleweed.

Both the song and the community garnered even greater notoriety in 1990 when an NBC television network crew arrived in Notrees to tape a Christmas Eve segment for the Today show, which would focus on the continuing effect of the 1980s bust in the petroleum industry. At the invitation of the NBC producer, Wilkinson participated in the taping, singing “The Tumbleweed Christmas Tree” live in front of the television cameras. Millsie King, the former postmistress of Notrees, ranked the event as “quite a to-do. A lot of the town’s old-timers came back for the filming, and everyone helped decorate a tumbleweed. We used… buttons on a string and tinfoil chains made from chewing gum wrappers, just like in Andy’s song.” “The Tumbleweed Christmas Tree” continues in regular rotation on Permian Basin radio stations during the Christmas season.

Even though a roughneck could normally expect to earn a higher wage than most, “The Tumbleweed Christmas Tree” does point to the economic risks that followed an oil field worker and his family. Times were not always flush, but a job in the patch still offered a possibility to get ahead. Wilkinson’s composition fits nicely with other accounts of men and women who grew up oilfield children. As Elmer Kelton, who spent his youth on the McElroy Ranch near Crane, Texas, during the town’s oil boom days of the late 1920s, pointed out, “Everybody close to the patch was on a somewhat equal economic level [and] the fact that there was no one to envy gave Crane and oilpatch towns like it a sense of equality, of fellowship. Furthermore, “Because no one had reason to feel either superior or inferior, there was a strong sense of togetherness… a feeling that we’re all in this together.” Or as Andy Wilkinson’s chorus proclaims:

Christmas Eve in Notrees, Texas,

Wind blowin’ through the cactus,

Santa Claus was a rich kid’s saint and a poor kid’s dream.

But I’d trade every fancy present

I ever had, or ever will get

For the night of the tumbleweed Christmas tree.

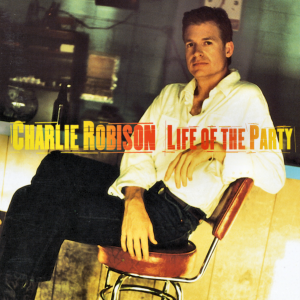

Charlie Robison was born in Houston in 1964 and raised on the family ranch in Bandera County. After high school in Bandera and a brief stint at Southwest Texas State University (now Texas State University) in San Marcos, Charlie drifted up the Interstate to Austin in the mid-1980s to join the city’s thriving music scene. He played with Chaparral, Two Hoots and a Holler, then formed the Millionaire Playboys. After a decade of making music in clubs and on the road, Robison recorded his first album, Bandera, in 1995. The Nashville music establishment soon came calling; however, it eventually became apparent that his independent approach to his craft and performance didn’t fit in Music City USA.

Journalist Don McLeese has characterized Robison’s “swagger” and “cocksure bravado” as “troubadour storytelling [with] a rock ‘n’ roll attitude.” According to Charlie, “I write about myself, but I put them in the third person. I mask my struggles by making them someone else’s… My writing goes deeper than it looks.” Robison’s second album, 1998’s Life of the Party (Lucky Dog CK 69327), offers several excellent examples of this songwriting philosophy, including two petroleum-related compositions: “My Hometown” and “Loving County.”

The theme of “My Hometown” is the ceaseless draw of the singer’s old stomping grounds. No matter how often he leaves with intentions to make the move permanent, he always decides at some point to “head my ass back home.”

Well, I had a buddy back in ’81 and we made ourselves a great pact

We were headin’ for the new pipeline, we were never comin’ back

We worked 80 hours makin’ time and a half but La Grange was too damn hot

So we drove back home here at the end of the week and we spent it all on pot

As for the reference to pipelining, “During my freshman and sophomore summers in high school, I worked as a welder’s helper on a pipelining crew on a ranch in Giddings,” Charlie said, “And I got to know roustabouts and ranchers involved with the oil field.”

Giddings (Lee County) and La Grange (Fayette County) are far removed from the Permian Basin, but Robison put these encounters to good use in “Loving County,” an oil patch tale of love, murder, and betrayal.

Loving County is positioned on the Permian Basin’s western edge just south of the New Mexico state line. Since the first discovery well was tapped in 1925, oil and gas drove the local economy, but the population (or lack thereof) is what continues to contribute to the county’s notoriety. For years, Loving County—remote, desolate, and arid—has been a contender for least populated county in the United States. With fewer than 100 permanent residents, the populace swells to more than 300 each day when oil field crews commute in from Pecos, Odessa, and Midland.

The setting of “Loving County” is deserving of a Jim Thompson byline. Thompson, the king of pulp crime fiction, in fact spent time in the West Texas oil fields in the mid-1920s soaking up the culture, which he later incorporated in four of his novels with a cast of grifters and losers who populate a land where murder on impulse is commonplace. In Robison’s scenario, a roughneck based in Odessa falls for a pretty young girl from Pecos. But she runs off with an “oil company bum ’cause a diamond was not on her hand.” The roughneck turns to the bottle for consolation before fate intervenes.

I walked in that bar and I drank myself crazy

Thinking about her and that man

When in walked a woman lookin’ richer than sin

And ten years’ worth of work on her hand

Well I followed her home and when she was alone

I put my gun to her head

I don’t recall what happened next at all

But now that rich woman she’s dead

He then takes the ring—“the diamond how it sparkles in the lights of Loving County”—and proposes marriage to his flighty lover. Instead of keeping mum about the engagement as he asks, she shows off the ring in town, “and her diamond how it sparkled in the lights of Loving County.” The dead woman just happens to be the sheriff’s wife. The lawman quickly tracks down her murderer in El Paso, on the run dazed and confused: “See I’d lost my mind on that broken white line/Fore I ever reached Balmorhea.” After the arrest, the sheriff buries his wife with the recovered ring on her hand. As for the Pecos gal, “Now she’s in Fort Worth and she’s just given birth/To the son of that oil company man.”

Robison confided to the Austin Chronicle’s Andy Langer, “I’m the only one that really knows ‘Loving County’ is about me… that I was going out with a wealthy woman when my career wasn’t going well. It’s a metaphor for what you’ll do in your life to be someone you’re not.” The dirge-like pacing of the melody further contributes to the foreboding and a sense of the inevitable. “The sparseness, plus the Loving landscape, lends itself to the song,” Robison added.

After his trial and conviction, the roughneck is incarcerated on the other side of the state, but for him the lights of Loving County have not dimmed. “Sometimes they let me look up at that East Texas sky/And the rain on the pines oh, Lord, how it shines/Like my darlin’ little diamond in the lights of Loving County.”

For all the song’s bleakness, its poignancy has touched a chord with many listeners. Brandon Cook, the blog creator and host of Lone Star STOMP, was in the audience for a Charlie Robison concert at Dos Amigos Cantina in Odessa in 2011. He reported that “a highlight was when [Robison] hit the opening to ‘Loving County’… Hearing a room full of Odessa roughnecks and roustabouts yell along [with the words] was certainly something.”

Joe W. Specht is at work on Smell That Sweet Perfume: Oil Patch Songs on Record, a project focusing on commercially recorded songs with petroleum-related themes as sung/written by performers with roots in the Gulf-Southwest. If you have a song that fits, contact him at jspecht@mcm.edu.