Sam Baker and Buckshot Bradley made their marks singing about life out where the derricks stand tall and the pump jacks keep rocking to that steady rhythm.

by Joe W. Specht

Sam Baker is well aware of the darker side to the oil patch. While attending North Texas State University during the 1970s oil boom, he alternated semesters employed as a bank examiner traveling in a Chevrolet El Camino with one suit of clothes. His team regularly audited the transactions of financial institutions in West Texas. “We were in Midland, Odessa, Kermit, Fort Stockton, and even Abilene,” Baker confirmed. “Optimism ran rampant… the bankers had incredible confidence—little realizing the 1980s bust was right around the corner.” Outside the boardrooms, “I ran into oil field people everywhere… mud pumpers, tool pushers, roughnecks.” Baker also had a family tie to the patch: his grandfather was a petroleum engineer. Subsequently, he incorporated this first-hand knowledge into two of his songs, “Truale” and “Odessa.”

Sam Baker was born in 1954 in Itasca, Texas, a small town in Hill County about equal distance between Fort Worth and Waco. The hymns his mother played as the organist at the Itasca Presbyterian Church and the platters in his father’s record collection, which included Lightnin’ Hopkins and Johnny Cash, framed his early musical listening. Graduating from North Texas with a degree in General Business, Baker eventually quit his bank examiner’s job and moved to Terlingua, where he worked as a whitewater rafting guide on the Rio Grande. In 1986, on a tourist outing in Cuzco, Peru, a terrorist bomb explosion seriously injured him; the incident left Sam without the use of three fingers on his left hand, partial deafness, and head trauma that affected his speech and memory.

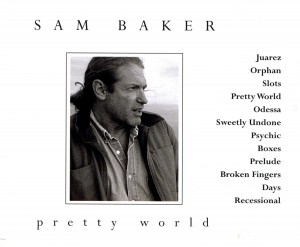

After a lengthy convalesce, Baker returned to work as a bank examiner, writing short stories on the side, dabbling with poetry. Chris Baker-Davies, Sam’s sister, adapted three of the poems as songs on her 2000 album Southern Wind. Soon after, Baker started performing at open-mic nights in small clubs in Austin (he had settled in the Capital City in the early 1990s) picking guitar left-handed, chording with his good right hand. And finally in 2004 at age 50, he released mercy (sambakermusic.com), the first of four highly acclaimed albums.

Baker’s abilities to draw precise, affecting portraits are often singled-out by critics and fans alike. For Sam, the creative process is a waiting game: “At some point, the characters take over and tell me what to write… My job is to give them the time and space to do what they need to do and say what they need to say.” “Truale” from the mercy album is a fine example.

In “Truale,” petroleum is omnipresent as the story unfolds to Baker’s cadence-like vocals, chanting the rhythms of the oil field.

There was oil

Oil to be found

Everywhere you put a boot

There was oil in the ground

Oil in the ground

Oil in the mud

Pump long enough

It gets in the blood

A young woman celebrates her 15th birthday with “a roughneck with a hand-done tattoo.” They take off “in his hot rod four forty two” and end up in Dallas “in a family way.” But the story takes a different turn from the usual scenario of girl runs off with boy, boy leaves girl pregnant and in the lurch, girl shamefully slinks back to her family. Instead, 15 years later, the woman returns to the family ranch, “Just her and the girls / Never said why she left him / But she wore cultured pearls.” The prodigal daughter refuses to fill in the blanks for her father: “No questions / No lies.” And now she cruises the countryside in “a t-bird with the top down / A cold beer between her thighs.” When asked how our heroine made her way so successfully in Big D, Baker demurs and grins, “That’s for you to decide.”

“Odessa” is included on Baker’s second album, pretty world (sambakermusic.com), recorded in 2007. Unlike the woman in “Truale,” who takes control of her destiny, in “Odessa,” Baker spins a tale of “an Odessa boy with a daddy in the money,” whose life slips irrevocably out of control. Sister Chris, who provided harmony vocals on “Truale,” opens and closes “Odessa,” singing the first and third verses of Stephen Foster’s “Hard Times Come Again No More.” However, in an ironic twist, the hard times for this family have not been caused by poverty but just the opposite.

He never learned to work but that never really mattered

‘Cause the dark crude flowed

The wild oats scattered

Dark crude flowed

He fought he flattered

And he got what he wanted

It was the only thing that mattered

The spoiled rich kid played football for Odessa Permian “back in the 1970s boom.” He drives a Corvette. Life comes easy. “The big jacks pumped / Pulling cash from the Permian field / Cabinets full of high-grade scotch / Garage full of high-speed steel.” The entitled, reckless attitude gets a girlfriend killed when he “rolls” the Corvette, but his father hires a high-priced lawyer to settle the case. His mother takes to the bottle: “She kind of knew.” Years later with both parents gone, he’s an old man living alone in the family mansion. He never married. More significantly, he’s haunted by the memory of “the girl who was penned in the Vette / Talks to her everyday / Her face was blood and diamonds / He remembers her that way.”

The narrative reality of “Odessa” is further reinforced by actual eye witness accounts. In his capacity as a landman for 30 years, Clarence C. Pope saw the destructive effects that oil field wealth could have on subsequent generations. Pope substantiated Baker’s observations: “Most of the people I knew who suddenly came into big riches just weren’t able to handle it. One way or another it ruined most of them or at least ruined their sons and daughters, and their grandchildren.”

Based in San Angelo and fronted by Clete Carillo, the group’s principal songwriter, Buckshot Bradley regularly toured the West Texas barroom circuit from 2007 to 2012, mixing originals and cover songs in the mode of their Texas-Red Dirt Music heroes Jason Boland, Wade Bowen, and Reckless Kelly. The band made multiple appearances at Crude Fest, a jamboree billed by promoters as three days and three nights of the biggest oil and gas celebration in Texas and held each year on the Star Ranch in between Midland and Odessa.

In 2009, Carillo and his mates—Robert Raney on bass, John Gill on drums, and then lead guitarist Adrian Blanco—recorded a self-released compact disc, Pumpjack, at the Honey Hut studio in Robert Lee, just up the road from the Concho City in Coke County. Rowdy and boisterous, with a sing-a-long chorus, the title song proved to be a readymade anthem for the band.

So meet me at the pumpjack

Well, I don’t care what time we get back

Sittin’ way too close to someone’s daughter

Throwin’ down some Shiner Bock

When I’m broke it’s Keystone Light

Nothin’ like watchin’ the sun come up at the pumpjack

Well, hell, why don’t you meet down, down at the pumpjack

Pump jacks (nowadays proper parlance in the patch is “pumping unit”) are, of course, as commonplace as mesquites in the Permian Basin often dotting the landscape as far as the eye can see. Affectionately known as a “noodling donkey,” “grasshopper,” “horse-head,” or “thirsty bird,” the pump jack has become an archetypical symbol of the petroleum industry frequently displayed on company logos and a variety of commercial products. Various devices have been used since the nineteenth century to extract oil from the ground. Walter Trout developed the now-familiar counterbalanced pump jack in 1925 in Lufkin, Texas, for Lufkin Foundry & Machine, and, with continual technological upgrades, it remains the workhorse in the oil field.

The first verse of “Pumpjack” sets the scene. “When you’re headin’ west down I-20 / Know you’re getting’ close to the West Texas plains / When you say, ‘What’s that smell? Well, it’s money’ / You can see those derricks miles away.” So grab your girl, some beer, and “loaded up on 30s off we go.” “30s” being street jargon for the prescription drug Percocet 30 mg, taken recreationally for a euphoric high. You have to be ever watchful, though: “Well, someone said they spotted the sheriff along the highway / We’re at a different pumpjack than the other day.”

Since oil companies built roads, usually made of caliche (a calcium rich surface soil) mixed with gravel and oil field waste, to get to and from the well site, this made the locale accessible to would-be Casanovas looking for a secluded place to make out. “Well, she grabbed my hand said, ‘Boy, you ready?’ / Well, we fogged up the windows in my old Chevrolet.” These good-time Charlies could also dance the evening away on the caliche pad, which was constructed to provide a stable foundation for the rig platform and subsequent pumping operation. Turn on the car radio, open the doors, and scoot a boot “with Willie Nelson on the radio all through the night.”

There were other sounds in the air, too. Oil field historian and folklorist Bobby Weaver reminisced about an oil patch rite of passage: “When I was a teenager we always took our girls parking out on some lonely location where a pump jack was running. I can almost hear those old one-lunged engines popping… another thing we did was ride the pump jack like a bucking horse… playing rodeo.… [We] never gave it a thought to what might happen, only to the thrill of the moment.”

Elmer Kelton, in his capacity as farm and ranch reporter for the San Angelo Standard Times and later as editor of Livestock Weekly, collected several pump jack aphorisms from ranchers, who had a jocular appreciation for the lease money and royalty payments that allowed them to stay on the land through hard times of drought and depressed livestock prices. For example, “A standing joke says the best mineral supplement for cattle is a working pump jack.” Moreover, a pump jack provided “the most rewarding type of shade for cattle or sheep….” And as Buckshot Bradley’s “Pumpjack” makes clear, the caliche pad was not only a gathering place for cows but also a retreat for young folk to rendezvous and social network.

Joe W. Specht is at work on Smell That Sweet Perfume: Oil Patch Songs on Record, a project focusing on commercially recorded songs with petroleum-related themes as sung/written by performers with roots in the Gulf-Southwest. If you have a song that fits, contact him at