MIDLAND, TEXAS—When Harold Hamm and a few members of his executive staff sat down with PB Oil and Gas Magazine in the Petroleum Museum in this oil-centric capital one sunny day this fall, the founder and leader of Continental Resources was keeping a timetable that would soon see them huddling up with the Permian Basin Petroleum Association’s executive committee. Their agenda matched the committee’s—it was all about industry advocacy. Always in the vanguard for oil and gas—that has been Hamm’s hallmark. Maybe no one in American energy has championed harder and longer for the hydrocarbons cause than Harold Hamm.

MIDLAND, TEXAS—When Harold Hamm and a few members of his executive staff sat down with PB Oil and Gas Magazine in the Petroleum Museum in this oil-centric capital one sunny day this fall, the founder and leader of Continental Resources was keeping a timetable that would soon see them huddling up with the Permian Basin Petroleum Association’s executive committee. Their agenda matched the committee’s—it was all about industry advocacy. Always in the vanguard for oil and gas—that has been Hamm’s hallmark. Maybe no one in American energy has championed harder and longer for the hydrocarbons cause than Harold Hamm.

And yet Hamm and his team are quick to lift up their Midland peers. One team member, Blu Hulsey, who is seated with Hamm and who serves as Continental Resource’s SVP of Government and Regulatory Affairs, says, “It can’t be overstated how important that room of leaders is [here he nodded toward the room where the PBPA officers and key team members were soon to gather] to our industry.”

Hamm, one of the nation’s wealthiest individuals, at a net worth approaching $20 billion, could easily delegate this task but he has made the trip personally to the nerve center of the nation’s biggest oil basin so that he can help strategize for the industry’s, and the region’s, sake.

And then, too, there is a culture for him to absorb here. Oil industry observers automatically associate the name Harold Hamm with the Bakken Shale of North Dakota and Montana. But Continental Resources took a huge stake in the Permian when, two years ago, they bought out the Delaware Basin holdings of Pioneer Natural Resources. That makes Continental one of the biggest-and-yet-least-known players in the Permian.

It’s easy to imagine that Hamm and his cohorts want to establish good-neighbor status within the Permian community, and this year they’ve gone about it with gusto, making this swing as well as committing one of their executives, attorney Will Houser, to the PBPA Board of Directors for the current term. And it’s easy to imagine that Continental Resource’s new partiality for the Permian is a good thing for the Permian, bringing yet another strong player and strong industry voice into the Permian Basin and PBPA fold.

With the Permian Basin producing roughly half of the hydrocarbon molecules that comprise America’s total output, the messaging that goes forth from far West Texas and New Mexico is of national import, always.

The words “optimism” and “optimist” come up with frequency in Hamm’s book, and his sentiments and actions are consistent with that theme. He has been an ambassador for the American Energy Renaissance, as he calls it. A friend of President Trump and other key national figures, Hamm has ties with the highly influential.

In 2011, the Wall Street Journal published their article, “How North Dakota Became Saudi Arabia,” citing Hamm as the main factor in North Dakota’s ascension. In 2012, TIME Magazine named him as one of their “100 Most Influential People in the World.”

Former U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said this in his foreword to Hamm’s 2023 book Game Changer: “I hope readers will appreciate Harold’s exceptional life and understand the truth that lies at the center of it. As we look toward the future, understanding the true advantage that American oil and natural gas provide is essential to our economic well-being and national security.”

Hamm told PB Oil and Gas Magazine that PBPA does a good job.

“These associations handle a lot of issues locally and also they hook up with national organizations like the Independent Petroleum Association of America [IPAA], the Domestic Energy Producer Alliance [DEPA], the American Petroleum Institute [API], and others, to make things happen on a much broader scale. They’ve been very supportive of the ‘national issues,’ as we call them. Like the lifting of the ban on crude oil exports. The industry was able to do that. It was something I played a role in. And Blu [Hulsey] played a big role in that, too.”

It’s been a long road for Hamm, with more than 55 years in oil and gas.

In his book Game Changer, Hamm tells a little about his early years as the 13th child of a poor, sharecropping family in south central Oklahoma. “My dad was a tenant farmer,” Hamm writes. “He didn’t even own the land where we lived. Every autumn our family would pile into the back of our pickup truck and drive to West Texas to pull cotton to make extra money. The whole family participated. I was five years old picking cotton bolls and piling them up in the middle of the row for my dad to swoop up into the cotton sack. We were paid by weight—a whopping two cents per pound.

“Our cotton-picking jobs would end around Christmastime or when the first snow fell. That was the signal to return to school. Since my brothers, sisters, and I had to forgo school for most of the fall to help support our family, I always started the school year a little behind my fellow students when it came to the curriculum. I had a burning desire to learn, and I wanted to be first in the class (and never last), so I always managed to quickly catch up.”

Hmm in the kitchen of his first apartment, in Enid, Okla., when he was cramming in a midnight study session. At the time was attending high school and working a 60-hour week.

If there ever was a real “Horatio Alger” story in the oil business, surely Hamm’s story qualifies. (In fact, in 2016 he was awarded the annually bestowed Horatio Alger Award by the Horatio Alger Assocation.) At the time, Hamm told the Association that one of the reasons he became interested in oil and gas in the first place is because he saw the generosity of oil industry leaders. “Frank and Jane Phillips gave away every dime of their huge oil and gas fortune. Waite Phillips, Sam Noble, the Skellys, the list goes on and on of oilmen and women who gave their wealth away to make their community and the world a better place. In Oklahoma, most of the oil people I have ever known fit that same mold.”

In 1966, at age 20, Hamm, a self-described “blue collar worker,” bought a truck to get himself into self-employment. In 1967, he incorporated his E&P, the Shelly Dean Oil Company, which would eventually become Continental Resources (though this venture would remain relatively dormant for a number of years). In 1968, he expanded into oilfield service. In 1974, shortly before his 30th birthday, he enrolled in college to study geology. He would take a lot of coursework but eventually departed school prior to graduation because of familial and business obligations.

By the 1980s, he and a partner, Les Phillips, were running the largest oilfield service company in Oklahoma, and also were active in five surrounding states. By the 1990s, he had shifted his focus to exploration, and ventured into Montana and North Dakota to wildcat new fields there. Then came his entry into the Bakken, and the rest is history.

So why did he make the move into the Permian Basin?

Said Hamm: “We’d actually done quite a bit of geology work out here prior to that [purchase]. Actually, at the time we bought Pioneer’s [position in the Delaware], we probably had maybe a hundred thousand acres of oil and gas leases. But we didn’t have a lot of oil and gas production. Just leasehold.”

Asked how Continental Resource’s Permian play compares to the company’s operations in three other basins—the Bakken in North Dakota, the Powder River in Wyoming, and the SCOOP/STACK in Oklahoma—Hamm says the Permian is clearly different. But he finds it bears the greatest similarity to Continental’s SCOOP/STACK position, which he alternately refers to as the Anadarko Basin and the Woodford Shale. “Southern Oklahoma has a great legacy of production, and the Permian is like that. They’re both 120 years old. So you’ve got legacy production and also, in Oklahoma, you’ve got the abundance of pay interval, which you have here in both the Midland and Delaware basins.”

As for the comparison between the Permian and the Bakken, Hamm said their main similarity was in depth. You can get into some deeper stuff here, but in the Bakken the depths can be similar—anywhere from 9,800 to about 10,200 feet. But it [the Permian Basin] is one heck of an oilfield.”

Asked why he thought Pioneer Natural Resources sold their Delaware position to Continental, while holding onto their Midland Basin position for a year or more longer, only to sell it to Exxon-Mobil, Hamm said he thought the sequence made sense at that time. “It was for ease of operation,” he said. “Most of Pioneer’s production was in the Midland, and so simply for ease of operations, it fit. And Scott [Scott Sheffield, then-CEO of Pioneer] wanted to carve some debt down, and so he made a quick sale to us and was able to do that. Of course, that paved the way, I guess, for his big deal with Exxon later.”

Flying was a love of Hamm’s, and he would eventually log 6,000 hours crisscrossing the oilfields of the Mid-Continent. Here he poses beside his first aircraft, a 1968 Mooney Executive.

Hamm said that his company had looked at the Permian Basin as early as the 1990s, when Continental was doing pioneering work in horizontal drilling in the Bakken. “We thought horizontal oil would work here,” he said. Such a move would have predated horizontal drilling (on a sizeable scale, anyway) in the Permian by a good many years. “Our company drilled the first-ever horizontal oil field in the world with the Red River B production in the Cedar Hills [play].”

Part of what Continental had learned there was how well horizontal drilling would work in thin-bedded reservoirs. “The Red River B reservoir was only about 14 feet thick. It’s 250 million barrel field. And our company and one other were the only companies ever to drill a well in it. So it was completely developed with horizontal wells.”

In 1993, Hamm was recognized as Member of the Year by the Oklahoma Independent Petroleum Association.

Hamm tells his company’s story in depth in his 2023 book, which has sold some 60,000 copies and is still going strong. “Nobody had told the complete story of horizontal drilling,” he said. “It is such a phenomenal thing, and it brought about the Energy Renaissance in America. Horizontal drilling took us from less than five million barrels a day to 13.3 million, which is where we are now. And as for natural gas, it took us from thinking we were going to need to import natural gas to [instead] exporting 15 MCF a day, and going to 25 MCF a day by 2026. You ask yourself about the turnaround in that and what brought that about? One thing. Horizontal drilling.”

Hamm, in his media appearances and speaking engagements around the country has made a big point about horizontal drilling being a bigger factor than hydraulic fracturing, when it comes to revolutionizing oil and gas extraction. Turning the bit meant far greater exposure to payzones, and that has been the most critical development.

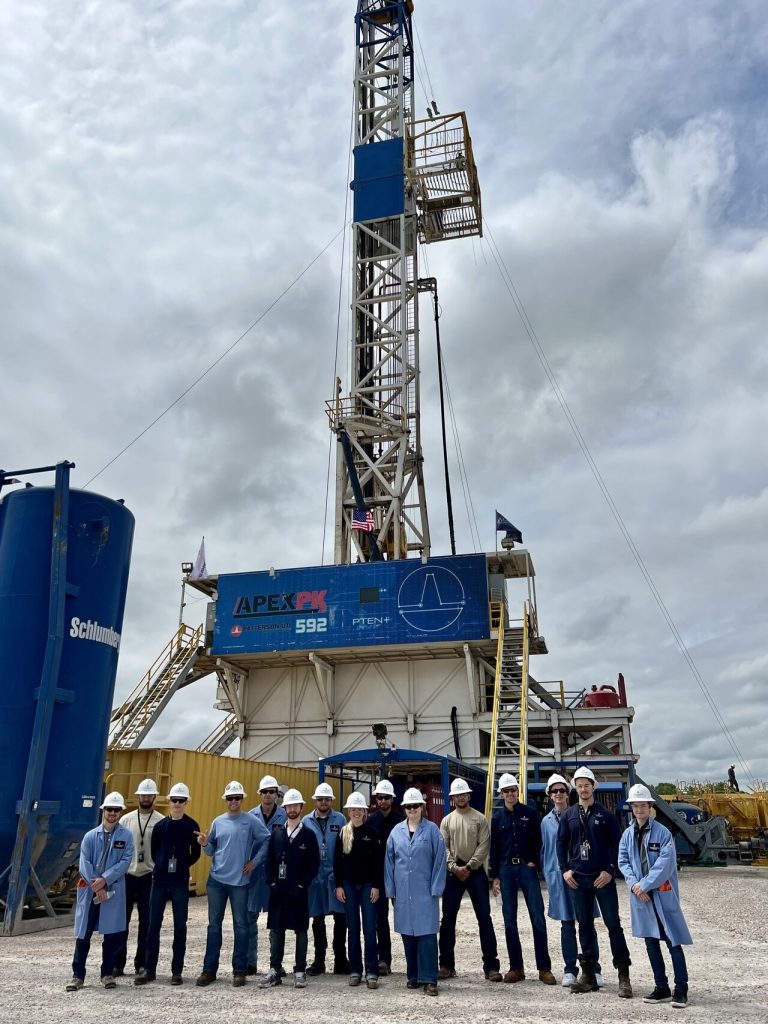

Continental Resources interns had the opportunity to see the drilling life cycle in action earlier this year, spending a full day on location for the company’s annual intern rig tour.

“The book has been a great tool to change the narrative somewhat and tell it like it is,” Hamm said. “And it’s been a big seller. When I wrote it, I didn’t think anybody would read it.” He smiled. “But actually, it’s a pretty quick read, as anyone will find out.”

In terms of community service, there have been two big developments for Hamm.

“Our foundation, the Hamm Family Foundation, has three pillars,” he said. “One is education, which helped me out the poverty cycle. Health is another. (The Foundation built and runs the Harold Hamm Diabetes Center at the University of Oklahoma.) And the third pillar is energy advocacy. (The Foundation created the Hamm Institute for American Energy, headquartered in Oklahoma City.) We want to advocate for this industry that’s so wonderful. This industry that’s done so much for me and my family.”

Asked about his opinion of his friend Donald Trump, Hamm says that the President is a wonderful person. “He’s very smart, a highly intelligent fellow, and he loves America. He wants to do the right thing with the country. I don’t know why anybody with his wealth, his everything… would want to run for that office [and go through what he has gone through], but the reason he does it is because he loves America and he wants to help America. And he has a great deal.”

Sounds a little like Harold Hamm.

Let’s close with a thought Hamm shares in his book. A moment of self reflection. He says,

“There is a part of me that gets excited about… opportunities to share why energy is the key driver of America’s economy and what is needed politically to keep the engine running. I suppose that’s because I am a farm boy at heart, always an optimist believing that good things will come from those interactions, and because maybe I will inspire the next generation, that their voices can also make a difference.”

Make a difference. It’s what you’re here for.

Hamm recently traveled to South Korea, where his book was released in the Korean language. He spoke as part of Korea University’s lecture series, discussion the positive impact clean-burning natural gas can have on air quality globally.

Jesse Mullins, editor of Permian Basin Oil and Gas, grew up in Oklahoma about 12 miles from where Harold Hamm did.