By Paul Wiseman

“What the world needs now

Is light, sweet crude…”

With apologies to Burt Bacharach and Dionne Warwick for that song hack, its truth is nonetheless valid—if you add natural gas to what’s needed. Since Congress reopened the U.S. oil market to exports in Q4 2015, the oil- and gas-rich Permian has dived in head-over-heels, supplying oil and natural gas to a world now in crisis due to war-inspired embargoes. The Basin’s massive reserves connect by pipeline to refineries and export terminals in Houston, Corpus, and elsewhere without crossing the regulatory black holes otherwise known as state lines. It is a dream come true for all three streams: up, mid, and down.

The United States as a whole is exporting more oil and gas than ever before, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). In September, the agency reported, “U.S. exports of petroleum products averaged nearly 6 million barrels per day (b/d), the most first-half-of-year exports in Petroleum Supply Monthly data, going back to 1973. U.S. petroleum product exports increased in the first half of 2022 by 11 percent (596,000 b/d) compared with the first half of 2021—the fastest growth rate for that time period since 2017. Nearly all petroleum products contributed to increased exports, and the largest volumes came from distillate fuel oil and hydrocarbon gas liquids (HGLs), which include propane.”

An Export Expert

Aaron Brady, Executive Director, S&P Global, said total U.S. exports of just crude oil hit a new record in July of 2022 at 3.8 million barrels per day. “Most of those exports are moving out of the Gulf Coast.” While that includes a few exports from Alaska and some pipeline exports to Canada (the United States and Canada trade light for heavy oil to meet refinery requirements), most comes from the Gulf Coast and, therefore, the Permian Basin.

Pipelines carry some from the Eagle Ford and South Texas as well as the Bakken, Oklahoma, and Louisiana as well. About 80-85 percent of Gulf Coast exports consist of light, sweet West Texas Intermediate (WTI). As the name implies, most of that oil originates in the Permian, which includes the southeast corner of New Mexico.

Brady notes that one possible reason for export increases has been the Biden Administration’s release of oil from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR), creating a surplus that is available for export. The surplus-to-export opportunity is further boosted by Permian production increases that continue to break records month to month, a trend that began late in 2021.

Natural Gas and Natural Gas Liquids (NGLs)

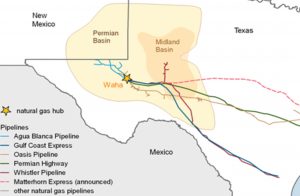

With the loss of Russian oil and natural gas due to sanctions based on its Ukraine invasion, the world also needs natural gas. The Permian is also producing record amounts of this substance, a significant portion of which is being liquefied and sent out through two main Gulf Coast terminals: Freeport LNG, and Chenier Energy’s Sabine Pass facility on the Louisiana side of the Texas/Louisiana border. Other gas production is exported in its original gassy state, through pipelines into Mexico.

In June of 2022, LNG exports dropped significantly due to the explosion and fire that shut in the Freeport LNG facility. Due to the resulting reduction in demand for supplies from Texas, natural gas prices also fell at the Waha Hub, where most of the Basin’s gas departs for markets, compared to the Henry Hub, which sets national prices. At this writing, ownership plans to begin reopening the terminal in early November, with a return to 85 percent capacity by the end of the month. They expect full capacity to resume by March of 2023.

NGLs including propane, butane, isobutene, ethane, natural gasoline, etc., also leave the Permian Basin bound for the world, some as raw materials and some in processed form.

Consultant Julius Leitner of Leitner Energy, through an association with Reese Energy Consulting, Inc., aggregated information from the EIA and the Texas Railroad Commission (TRRC) to estimate Permian Basin shares of the above exports.

For the period spanning January-June 2022 (most recent available data), total LNG exports from Texas’s two LNG export terminals, Cheniere’s Corpus Christi Liquefaction facility and Freeport LNG, totaled 680,058,395 MCF. January’s daily average was 4,215,945, dropping to 2,701,459, with the change mainly due to the Freeport explosion, which happened on the 8th of the latter month. Leitner estimates that, for the period, the Permian Basin accounted for 29.97 percent of total Texas LNG exports.

Natural gas pipeline traffic from the Basin to Mexico is also on the rise, says the EIA. Exports “have grown steadily in recent years, doubling from 0.6 Bcf/d in 2019 to 1.2 Bcf/d in 2021 as more connecting pipelines in Central and Southwest Mexico have been placed in service in the past three years,” said EIA analysts. The EIA reports 1.55 Bcf/d was exported directly from the Permian Basin in July 2022, the latest month reported.

Propane is another significant export product from a district known as PADD 3. PADD 3 (Petroleum Administration for Defense District) is one of five PADDs into which the United States is divided. PADD 3 encompasses New Mexico, Texas, and the Gulf Coast as far as Alabama. For the January-July 2022 period, Leitner says the region, dominated by Texas facilities, exported an average of 1,201 thousand barrels per day, 82 percent of which went to export. Production in the area is dominated by the Permian Basin.

Butane, which share’s propane’s ability to easily change from gas to liquid under moderate pressure, saw average exports of 300,000 barrels per day, which accounts for 66 percent of production for PADD 3. Much of that export traffic goes nearby, to South America, especially during the U.S. summer months, and to the Caribbean.

Pipelines to Paradise

Getting those Permian products to market—domestic or international—is a continuing see-saw battle. As production rises to record levels, pipelines of all types reach capacity, creating bottlenecks and price challenges as old lines are expanded and new ones built. Experts have predicted that capacity is about to cycle back into shortage mode, though several gas and crude lines are slated for completion through 2023-25.

As for getting crude overseas, the Port of Corpus Christi (POCC) was the first Texas facility to embrace exports. Until then the vast majority of Gulf Coast pipelines terminated along the Houston-Baytown-Beaumont corridor because of their high concentration of refineries making gasoline, diesel, and other fuels and products for the domestic market. While there are few refining options at POCC, the exports opportunities are growing rapidly. The port currently is the jumping-off spot for 60 percent of U.S. crude exports.

This POCC expansion began in 2019, Brady said, when several pipelines to the port began delivering oil to the port. And, as crude carriers get larger—the current champion is the VLCC class (very large crude carrier) that holds two million barrels—their draw gets deeper. Ports must adapt, or do a sort of daisy chain process where a smaller ship is loaded several times, then sails a short distance to transfer its load to the larger ship, a process that can take days.

VLCCs draw 75, a depth only currently available at the Louisiana Offshore Oil Port (LOOP), located offshore from Grande Isle, La. POCC and Houston have deepened their bays but not enough to fully load a VLCC.

Sailing Off in All Directions

With the war in Ukraine and the resulting boycotts of Russian oil, Brady pointed out that “increasingly, a lot of it’s going to Europe. That’s been a big shift this year.” In 2021, the United States sent 1-1.2 million barrels per day to Europe. “Now we’re seeing it approaching 1.7 million barrels per day,” he observed.

The next biggest destination is Asia, although shipments to India have dropped since February. That nation has taken advantage of sanctions, as Russia has shifted to selling its boycotted oil at a discount to whoever will still take it—and that includes India.

Still the U.S. exports about 1.5 million barrels a day across the International Date Line, mainly to South Korea, Singapore, India, and Taiwan. For LNG, the EIA reports that 39.5 percent of U.S. exports go to Europe, with the East Asia/Pacific region coming second at 34.1 percent.

Exporting the Future

For Brady, the future of exports from the Permian and elsewhere in the United States hinges on two questions: “Is production going to continue to grow? It’s been a little bit bumpy since the COVID collapse in 2020. U.S. production peaked at 13 million barrels per day right before the pandemic started and now it’s bumping up to around 12 million.” Which is still less than before. For U.S. exports to grow, production must continue to provide enough supply to export. “The Permian is recovering faster than other basins,” he observed.

“The other question is, what is going to happen to these SPR releases?” Those releases have averaged nearly a million barrels per day at times. As previously noted, that much oil added to the supply provides margin for exports.

“Will they be continued or renewed? They’re supposed to taper this quarter, but the administration could announce another round,” he said.

As stated, Congress reopened U.S. oil to export in Q4 2015, overturning that section of the 1975-enacted Energy Policy and Conservation Act, which had been a response to the events following the Arab oil embargo of two years earlier. Some in Congress are suggesting a return to pre-2015 restrictions, again in response to price rises resulting from production losses out of OPEC+. But, as Brady noted, oil markets are even more internationalized now than they were in the 1970s, so discontinuing exports would not likely disconnect U.S. oil from price increases related to overseas production cuts.

As one of the most prolific basins in the world, the Permian Basin is poised to be a significant force in oil, gas, and NGLs for both domestic use and export for the foreseeable future.