Of oil and gas’s three industry sectors—upstream, midstream, and downstream—midstream has been where the action’s at in 2018, and it’s driving decisions in both upstream and downstream as well.

By Paul Wiseman

Anyone who has ever held the business end of a garden hose while someone else—around the corner and out of sight—controlled the faucet has a general idea of how it feels to be a midstream company in the Permian Basin these days. The plants are in danger of drowning.

Greatly increased production from the Permian since prices began to rebound in Q4 2016 is the faucet that’s opening wider and wider on a daily basis. Midstream companies holding the hose are struggling to keep up with capacity. A long list of midstream projects, both oil and natural gas, are slated to come online starting in Q4 2019 and continuing into 2020.

As that hose fills up, it creates a variety of backlogs. The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) tracks 45 top companies it considers bellwethers of the industry as a whole. Earlier this year the EIA aggregated those firms’ second quarter reports and noted that “several U.S. oil companies with operations in the Permian region of Texas and New Mexico discussed increasing transportation constraints in the region. Insufficient pipeline takeaway capacity in the Permian Basin has contributed to significant crude oil price declines in the region compared with the U.S. Gulf Coast. The price of Permian crude oil reached more than $20 per barrel below Gulf Coast crude oil in August and in September. EIA expects these constraints to persist through mid-2019.”

As a result, some companies are moving expenditures out of the Permian and into other basins.

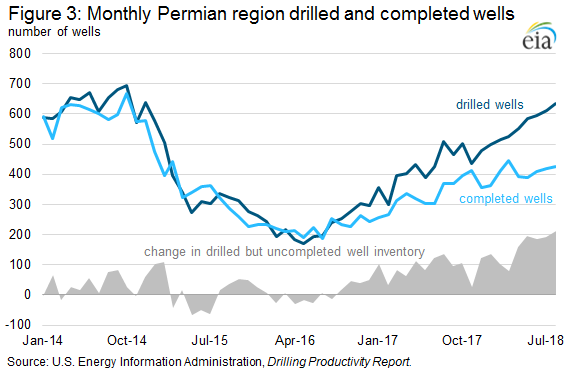

Others are continuing to drill but postponing completions until additional pipeline capacity becomes available. The graph on this page shows the rise in DUCs (drilled but uncompleted wells), especially since Q1 of 2017.

The list of in-process pipeline projects is long, most of which are one to two years out.

Ironically, natural gas pipeline capacity has been the real challenge—and it is fortunate that at least a little relief there came in July, with the completion of distribution networks in northern Mexico. The EIA reports that exports from Texas to Mexico rose from 4.4 Bcf/d in the first six months of 2018 to more than 5 Bcf/d in July due to the commissioning of several key pipelines south of the border. A significant portion of the increased flow is coming from the Permian Basin.

Eagle Claw Midstream, in partnership with Kinder Morgan Texas Pipeline, LLC, is among the companies working toward a solution. Eagle Claw CEO Robert A. Milam described how their Permian Highway natural gas pipeline project, slated to come online in Q4 2020, came into existence.

“We looked at several of the competing pipes,” during their own planning stage. “What Kinder Morgan brought to the table was interconnectivity on the market side,” he said. Eagle Claw did not want to just plug into facilities in Corpus Christi or Agua Dulce, as some other systems did.

“What Kinder brought was interconnectivity to their whole intrastate pipeline system. That made it pretty much a no-brainer to us that that’s the pipe we wanted to be on. Then it was a race to FID [final investment decision],” Milam said.

The FID came quickly because, with production outstripping takeaway capacity, the Permian Highway project lined up a “stellar anchor base of customers” and thus it was pretty much fully subscribed right away.

Currently a 50-50 partnership between Eagle Claw and Kinder Morgan, the deal is one whose percentages could change because Apache may exercise its option to acquire a percentage of the project.

Up till now Eagle Claw has been a small player, so connecting with the previously-mentioned blue chippers has vaulted the company into rarified air—a position Milam welcomes.

“We’re really excited about what that does for Eagle Claw,” he said, although he admitted that Q4 2020 seems like a long way off. “We think that really changes who we are and how we believe we’re perceived.”

Gas from this line will pass through the crowded Waha hub in Pecos County, but Milam stresses that the pipeline will also carry it out. With so many others running only into—and not out of—Waha, “We kind of think that may be where the train wreck happens.”

“We will also lay a residue line from our plants to PHP (Permian Highway Pipeline) there at Waha—and while it’s going to look like we’re laying a line to Waha—because of our ownership and dedication, it’s really that we’re taking gas through Waha straight to the Gulf Coast markets.” Eagle Claw has also connected with several direct-to-Mexico lines.

One thing driving the schedule for PHP, Milam said, was getting their steel order in from domestic providers before tariffs greatly raised prices on imported steel. “That was a big, big deal on trying to come up with domestic steel, and be the first one out. The next guys that go out will most likely face lengthy delays before they can get domestic steel again because this was such a large portion of the domestic steel production of the 42 inch coil.”

In some ways, however, Milam notes that adding gas pipelines only pushes the bottlenecks downstream.

“The thing that’s the tightest, I believe, today, is fractionation capacity,” in plants at Mont Belvieu. “We are seeing some curtailment of NGL (natural gas liquids) volume from dedicated acreage,” Milam said. He understands that Lone Star has a fractionation plant scheduled to open in March-April of 2019.

Yet another backlog, also involving pipelines at least to some extent, revolves around how to handle the increasing flood of produced water that accompanies oil production increases.

“Water is a big issue out here,” Milam noted. And with the September acquisition of Caprock Midstream, Eagle Claw is now in the water midstream business.

“I’m kind of excited about this water—you’re seeing a lot of private equity teams launch out into this water business, and it’s something that the producers have never been willing to turn loose of because it’s so vital to oil production. If you don’t take the water, you shut the well in,” which makes that more of a problem by-product than gas. Natural gas can at least be flared for a while, with proper permitting, but “if your water tanks fill up, you’re done.”

While the oil business has always had a water component that needed some attention, the proliferation of produced water dates back only to the ramping up of directional drilling. Its sometimes miles-long laterals combined with millions of gallons of water and thousands of tons of frac sand began unleashing a torrent in about 2011. As the number and percentage of fractured horizontal wells mushroomed, so did the water issue.

In just the last 2-3 years this flood has created a midstream for water—and that midstream is also feeling the pressure of greatly expanded drilling and production.

Sam Oliver is chief commercial officer for Blackbuck Resources, a water midstream company.

He said, “It’s a development of horizontal [drilling] programs that leads to more sand, more water on the front end, [then] more oil, more gas, more water on the back end. And when you start stacking rig counts on rig counts, the infrastructure that was in place in 2011, or 2005, or 2001 [was swamped].”

Even now, he said, many wells produce more than is expected, so water infrastructure planned at the same time as the wells is still not adequate. And pipeline projects move much more slowly than do drilling projects.

Plus, noted Blackbuck’s CEO, Justin Love, the rapid decline curve typical of horizontal wells requires continued drilling. “You can never plan for it,” he said. “By the time you drill your thousandth well over the course of however many years, how could you build your infrastructure ahead of time to accommodate that?”

And because drilling is a moving target, water pipelines laid today may either be inadequate—over-filled—or unnecessary as the drilling activity moves to another field, or slows due to a price downturn. Balancing the water supply with the need is the key.

Some industry veterans on the production side say they mostly produce water, with a little oil mixed in. Oliver says the figures bear that out. In the New Mexico portion of the Permian, the water cut is usually 2.5 times the amount of oil, while for some Delaware Basin wells the water is 10 times the oil amount. The average is closer to 4x water to oil.

The idea of producers sharing produced water among themselves in order to achieve that supply-demand balance is where water midstream companies like Blackbuck come into play. But getting producer buy-in is still a challenge.

Said Oliver, “I think that’s where commercial players like ourselves fit in that space—not to say that we act as brokers. But I think it’s easier for a Blackbuck to get into that space and bring two operators together with a plan and commercialize multiple pieces of a puzzle.”

Earlier in 2018, the EIA reported that the United States likely became the world’s number one oil producer, surpassing both Russia and Saudi Arabia. The Permian Basin is a major part of those production numbers—and they’re actually being restrained by pipeline challenges. Rail capacity is limited and trucking oil to refineries is cost-prohibitive.

So starting in Q4 2019, U.S. and Permian production could very well cement the United States as the world’s top oil producer.

Paul Wiseman is a freelance writer in Midland, Texas.