By Al Pickett, special contributor.

Blowout prevention, already a science, is an art as well, especially in new shale plays such as the Permian Basin. For drilling operations, finding good well service people is the key.

Safety has always been a top priority in the oil patch, according to Larry Chapman, but even so, as the well control expert himself observed, public scrutiny of the oil and gas industry has increased following the April 2010 Macondo well blowout, or “BP oil spill,” in the Gulf of Mexico. Eleven rig workers were killed in the British Petroleum offshore rig explosion that saw some 200 million gallons of crude spew from the bottom of the sea.

“Training has taken on a higher profile since the BP explosion,” Chapman said. “It was just an accident, but it changed public perception. We need a better PR [public relations] guy.”

Chapman is the president of Chapman and Associates, a Lafayette, La.-based company that conducts well control training, including ongoing classes that Chapman teaches at the Petroleum Professional Development Center at Midland College.

“Training has taken on a higher profile since the BP explosion.”

Government-mandated well control training, conducted by the Minerals Management Service (MMS), used to be required for off-shore drilling and obviously had an overlap with onshore drilling activities. But the MMS got out of the training business a number of years ago, Chapman pointed out, so the program fell under the International Association of Drilling Contractors (IADC), which oversees and audits the structured training program.

“The program that most people accept as the standard for well control training is WELLCAP, which stands for Well Control Accreditation Program,” he explained. “The training is for drillers, tool pushers, company people, and consultants. Although the program is no longer mandated, I think the Texas Railroad Commission requires at least one person on each rig that has received the training. Most companies are using the WELLCAP program for their employees.”

Chapman, who is a WELLCAP-certified instructor, noted that the number of those taking his training has picked up in the post-BP-accident era, even though offshore drilling was halted for more than a year because of a government-imposed moratorium.

“That has been softened by a lot of shale exploration,” he added. “That has made a big difference, with more rigs and more people working.”

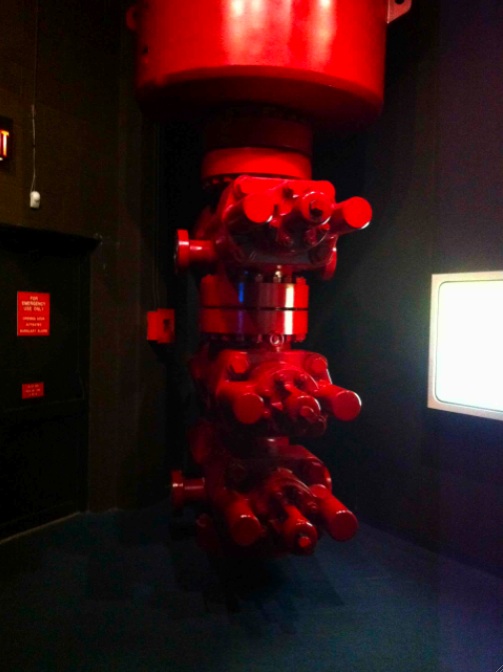

This hefty specimen of a blowout prevention resides in the Permian Basin Petroleum Museum in Midland. The door at left gives some sense of scale to the BOP.

Shale drilling from the Barnett in North Texas to the Eagle Ford in South Texas, the Haynesville in Louisiana, the Marcellus in Pennsylvania, and the Bakken in North Dakota has rig counts and people working in the industry at near-record numbers. The same is true, of course, in the Permian Basin, where the Wolfberry and Bone Spring plays have rig counts and drilling activities at levels not seen in nearly 40 years.

“Our training is designed to prevent kicks, blowouts, or, most importantly, loss of life.”

While drilling horizontal wells in shale rock has revolutionized the oil and gas industry in the last few years, it hasn’t changed the well control training that Chapman provides.

“We are still talking about porosity, permeability, and controlling pressure,” he contended. “The physics haven’t changed just because we are producing from a different kind of rocks. The pressure from the well is pushing up and you are trying to push it down. That hasn’t changed.”

The most important concern in terms of well control and blowout prevention in the Permian Basin, according to Chapman, is having experienced people working on the rig.

“The number one issue in the Permian Basin and everywhere is getting employees that are trainable and available,” he emphasized. “The number one issue is finding enough people to work. We can train you and get you up to speed. It used to be that you worked for a few years and learned by watching a mentor. Now, we have to do it at a faster pace. There aren’t enough people to have guys watching someone else work. It is a unique challenge. We have a lot of people to get ramped up.”

Chapman said the WELLCAP program provides 40 hours of training in a week that he equates to a semester class. He pointed out that people often ask him if they can be hired by a company if they pass the training program. It doesn’t work that way, however, according to Chapman.

“Service companies work hard with training.”

“I tell them that if they get the opportunity [and] find work with a service company or drilling contractor, then they will send you to the school,” he explained. “Our training is designed to prevent kicks, blowouts, or, most importantly, loss of life.”

Although a drilling rig such as the Deepwater Horizon involved in the BP explosion can be a $1 million-a-day operation, Chapman said money is not the most important thing when discussing well control and blowout prevention.

“You can always clean up the oil or buy new iron, but you can’t replace the folks working on the rig,” he emphasized. “Safety has always been important, but everyone has safety an even higher priority these days.”

Planning and preparation

Dan Bohannon, senior vice president of operations for CUDD Energy Services in its Midland office, cited planning and preparation are the two most important things in addition to training in well control and blowout prevention.

“We do a lot of rig inspections,” he said, “to make sure the flow path is connected properly and there is a double barrier in case one fails. Training is an issue, but we try to eliminate the pre-job possibilities by checking the blowout preventers [BOPs] and flow paths.”

Bohannon admitted there are still those in the industry who will try to cut corners, a mistake that can come back to bite them.

“The industry is gravitating toward API standards in other service work,” he stated. “Even in the Permian Basin, you can find a strange zone and get a kick that you weren’t expecting. We have even seen a well come in without the proper amount of pipe cemented in. How can you pump a well if you don’t have enough pipe? There is always the potential for more kick than people were expecting from new zones or some overcharged older zones. We still find new pressure pockets.”

Bohannon noted that the Abo Shale in New Mexico has a history of just such pressure pockets that can give a kick, causing well control issues. He said he expects the increased drilling in the new Bone Spring/Avalon Shale play in Culberson County could cause the same type of problem.

CUDD, which is based in Houston, is a world-wide leader in pumping and coiled tubing services, as well as well control.

“We are a legacy pressure control company,” Bohannon noted, “founded in 1978 by Bobby Joe Cudd, who was a legend in Oklahoma. He is from the same era of Red Adair and Boots and Coots.”

Bohannon agreed with Chapman that training, in addition to planning and preparation, is extremely important today.

“The experience level is getting thinner,” he lamented. “The last job I responded to, the kid who closed the pipe rams has been on the job four months. He reacted properly, but I’m not sure he knew why he did what he did.”

Workover Pressure Control

Much of the work in the Permian Basin, of course, involves well service or workover rigs. That training is not part of the IADC’s WELLCAP program, but the PPDC at Midland College offers a one-day course called “Well Service and Workover Pressure Control.”

Mike Cure, who owns Cure Consulting in Midland, said the course, which is designed to provide a common-sense understanding of the oil and gas industry, was first developed for a major service company in the Permian Basin. Cure has now been teaching the course at Midland College for nearly seven years.

Ninety-five percent of all blowouts are the result of human error.

“A lot of our work in the Permian Basin involves workovers and completions,” he continued, “where it is not controlling pressure coming from the well bore but pressure that we cause from pumping fracs, acid, nitrogen, water, or CO2. Those pressures and volumes are very high. The difference is that most of things we pump don’t catch fire. CO2, nitrogen, or water are not normally flammable.”

Cure equated his class to looking under the hood of car, trying to provide an understanding of how things work.

“We try to offer a common-sense understanding of how pressure reacts, how seals seal, etc. Just an understanding of how things work,” he added. “A good number of these workers don’t speak English as a first language, either.”

For example, Cure said he tries to explain in his class what is inside a valve, what seals are, and how non-compressible water reacts differently when pressure is applied when compared to compressible fluids or air that store up a lot of energy when pressure is applied.

“Service companies work hard with training,” he offered. “You can intellectually learn something, but you don’t really understand it until you do it.”

Cure agreed with Chapman and Bohannon that everyone is green today with so many new people and new equipment in the oil patch. Cure praised the PPDC and Midland College for the work it does in meeting the industry’s need for well control and blowout prevention training.

While blowout prevention equipment and the accompanying testing is critical in well control, there is no substitute for communication, planning, preparation, and proper training, according to all three well control experts, because it has been estimated that 95 percent of all blowouts are the result of human error.