How monetary policy pushed the industry over the edge.

by Chase Beakley

The Permian Basin has been inextricably tied to the global oil market since its inception, and although every warm body in the Basin knows this, there remains a feeling that the forces controlling their lives remain just beyond their understanding. And in truth, as the global economy has grown ever more integrated, the number of variables that determine the price of a barrel of oil has increased exponentially such that even the brightest minds in energy are often left scratching their heads and rushing to protect their asset(s). However, as the 1980s slowdown showed this region, and the 2008 Financial Crisis showed this country, surrendering to the complexity and blindly hoping that things will work out can be catastrophic.

Much has been said and written about the more obvious causes of the slowdown: OPEC’s unwillingness to curtail production, slowdowns in China and emerging markets, and the combination of debt and hedged prices that kept rigs drilling long after demand had fallen off. But very little has been said about the staggering, and in hindsight unhealthy, rate of growth in the Texas oil industry from 2010 to 2014 that led so many companies to overspend and overleverage, and what role quantitative easing (QE) may have played in that process.

A QE Primer

In order to understand the impact that QE might have had on the overcapitalization of the Texas oil industry, it’s important to understand what QE was and what it was not.

After Lehman Brothers folded in September of 2008, it became clear that the Federal Reserve would have to act to prevent the U.S. economy from sinking into a full-blown depression. The Fed needed to stabilize the financial institutions that had crippled themselves through the creation of toxic debt securities, and provide incentives for investors to put their money back into the market. The steady lowering of interest rates beginning in 2008 came as no surprise, but the economy was in such dire straits that the Fed made an extraordinary move, purchasing the toxic mortgage-backed securities and debt of Fannie and Freddie to stave off further volatility. This asset purchase would later come to be known as QE1, and showed that the Fed would, as chairman Ben Bernanke put it, “Do whatever is necessary” to support the United States economy. But while things began to level out in the following years, growth remained anemic and the long-term outlook dreary.

By 2010, interest rates were effectively zero, so the Fed needed to find another way to get money moving. In November of that same year, the Fed announced another round of asset purchases, $600 billion of long-dated treasury bills at a rate of $75 billion a month now called QE2. We could quickly get into the weeds about the mechanics of QE but the essence is this: this asset purchase decreased the yield of safe investments like treasury bills and government bonds, and signaled to the market that interest rates would remain low in the long term. This, the Fed hoped, would encourage investors to move money out of safe low-yield vehicles and into riskier investments with a higher returns.

It’s important to note that QE was designed not to increase the amount of money in circulation, which can lead to inflation. Although the Fed did print money to purchase assets from banks, that money was retained as reserves so that none of it could be introduced directly into the market. One would think that such an increase in commercial bank reserves would encourage those banks to lend more and therefore increase the money in circulation; however, even as the Fed’s assets grew and the banks’ reserves climbed, the velocity of money stayed low. Low velocity of money meant that there was little real increase in the money in circulation, despite the overall increase in the money supply and thus very little inflation. After the market recovers, the Fed plans to sell its assets and destroy the cash it receives, returning the money supply to pre-QE levels and shielding the market from inflation.

With that in mind, it’s clear that QE’s purpose was not to permanently alter the money supply, but to decrease long term interest rates beyond what could be accomplished with ZIRP (zero interest rate policy) alone, depress the yield of safe investment vehicles like government bonds and savings accounts, and encourage investors to seek higher returns in equity, corporate bonds, and commodity derivatives.

It’s almost impossible to assign direct blame to QE for any aberration in the market. By its very nature QE’s effect on the market is indirect, and that makes it impossible to establish a 1-to-1 causal relationship between QE and any market trend. Any effect QE might have had on a particular industry must be experienced in concert with a variety of other macroeconomic forces. However, given that the goal of QE was to push money out of safe investments and into riskier areas of the market, one could conclude that QE encouraged money to flow into emerging markets and commodity derivatives which supported high oil prices, and released a flood of capital on the Texas oil industry above and beyond what the actual market forces would have dictated.

All Roads Lead to Rome

Writing on quantitative easing’s effect on commodities for Reuters, John Kemp summarized the situation well in a 2010 blog post.

“The forecast effect on commodity prices… is impossible to quantify. Massive uncertainty surrounding other variables, the transmission mechanisms, and how QE will interact with investor preferences dominates any price forecast. It is essentially meaningless to say that $X billion of QE would add $Y to the price of a barrel of oil or a ton of zinc. The uncertainty is simply too large for the prediction to be useful,” Kemp wrote.

“But it is possible to predict [that] the effect on prices will be positive (since all the transmission mechanisms point in the same direction, from higher QE to increased investor demand for commodity derivatives and inventories).”

Kemp concluded: “It seems likely the biggest impact will be felt in markets where fundamentals are already strongest (given the non-linear nature of commodity pricing relationships and the heightened potential for bubbles to form as a result of positive feedback loops and self-validating price movements).”

By Kemp’s assessment, commodity-dependent markets with strong fundamentals would be the most likely to be effected by QE, and the likely result of such artificial growth would be positive feedback loops and self-validating price movements. Sound familiar to anyone?

One of the principal critiques of any QE program is that rather than cultivating growth across the entire economy, QE shoots capital like a fire hose into the most profitable sectors and floods them with money until they pop. Making savings accounts and bonds ostensibly useless forces investors to put their money anywhere else, and this can lead to a lot of money going to the same places.

In a paper entitled “Effects of U.S. Quantitative Easing on Emerging Market Economies,” Dr. Saroj Bhattarai, professor of economics at the University of Texas, found that, “QE led to an increase in capital flows to emerging markets while decreasing interest rates in those countries and appreciating their exchange rates [bilateral with the U.S. dollar].” This spike in American investing had largely adverse effects on foreign currency prices in several emerging markets, so much so that Brazilian Finance Minister Guido Mantega called the policy a “currency war.”

Dr. Bhattarai’s research shows that QE created a capital flight to emerging markets because they (the markets) provided much more upside than similar investments in the States, and that this capital injection had adverse effects on the markets in question. Did a similar capital flood wash over the Texas oil industry? Permian Basin oilmen think so.

“I think QE had a massive effect on the horizontal and frac’ing boom,” said Jeff Phillips of Orion Drilling. “Lower interest rates urged anyone with money to take it out of the bank and invest it, and with the stock market in flux, participating in a horizontal well with a 4-6 percent return almost guaranteed seemed very attractive.”

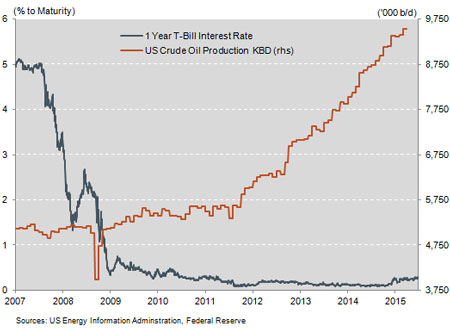

As interest rates shrank toward zero, United States oil production shot through the roof. One could argue that the innovations in horizontal drilling would have sparked this growth regardless, but data from Baker Hughes shows a spike in traditional vertical wells over the same 2010-14 period. Surely horizontal technologies had a lot to do with the growth in Texas oil during that time, but the surge in vertical drilling reveals that there was money to be made in oil outside of the opportunities new technology provided.

Keeping in mind that QE2 went into effect in November of 2010, and QE3, a similar Fed asset purchase, was announced in September 2012, these graphs start to look very interesting indeed.

Shortly after QE2 went into effect, equity investments in E&P companies were in vogue. Out-of-state tycoons and private equity funds lined up to buy portions of independent oil companies, and although equity is generally a riskier asset to hold, at that time every Permian Basin drilling company was growing at a shocking click and new ones were springing up every day. In an otherwise lackluster market, Texas oil looked bulletproof. Between 2010 and 2012, the rig count in the Permian Basin quadrupled.

But even those without the capital to buy chunks of equity could invest in the Texas oil industry. Retirement funds and nest egg savers needed a higher-yield replacement for bonds and savings accounts, and share of MLPs made the perfect substitute. Their legal structure protected shareholders from losses and they offered the same fixed income distribution as a bond or money market account, but with a much higher yield.

Leroy Peterson, of Patriot Drilling, was shocked by amount of money that flowed into the Basin. “It still blows my mind to think about the billions of dollars being spent just in the Permian Basin. For a while there, we had 600 wells going at an average of $5 million each, finishing every 20 days.” That comes out to $4.5 billion/month being spent in an area smaller than the state of Nebraska. The fire hose metaphor seems appropriate.

Jeff Phillips likely would concur. “All this money was driving up commodity prices, including oil and natural gas, fattening the profitability of producing wells,” Phillips said.

This is an important point. QE forced money into commodities derivatives and emerging markets, both of which buoy oil prices. Now the price of oil is determined by many more factors than U.S. QE, but it would be difficult to argue that QE didn’t support oil prices that were already high by historic standards. All signs point in one direction, upward.

So QE helped push investors to move money into the Texas oil companies, and encouraged market action that propped up high oil prices that in turn made Texas oil companies increasingly profitable and attractive to investors. The result was self-validating growth based more on artificial influence than real market forces—in short, a bubble, just like the housing bubble to which QE was a response.

Caveats and Conclusions

Just to reiterate, it would be intellectually dishonest to say that QE alone caused the U.S. oil industry crisis and subsequent global supply glut. There are a host of interconnected market forces at work on oil at any given time, and none can be assigned sole responsibility for volatility. However, all the signs suggest that QE played a part in the out-of-control growth and subsequent crash the Permian Basin oil industry experienced from 2010 to today, and there are lessons to be learned.

Michael Burry, the real-life fund manager who inspired the character in the Oscar-nominated film The Big Short, recently said in an interview, “Interest rates are used to price risk, and so in the current environment, the risk-pricing mechanism is broken. That is not healthy for an economy. We are building up terrific stresses in the system, and any fault lines there will certainly harm the outlook.” It’s clear that after the Financial Crisis, the U.S. economy’s relationship to risk came unhinged from reality.

Steve Pruett, of Elevation Resources in Midland, reinforced this point, saying, “Interest rates that were low for too long created incentives for investors without appropriate levels of risk and pretty soon 4 million barrels of shale production helped create the excess supply worldwide.” In the future, oil companies might be served by treating low interest rates more cautiously, and perhaps with the Basin as a case study, the Fed ought to be more hesitant to institute monetary policies that encourage mindless risk-taking.”

J. Chase Beakley is a freelance writer living in Odessa, Texas. His article on the impact of the recent downturn on Midland and Odessa (viewed comparatively) appears in the April 2016 issue of the Permian Basin Oil and Gas Magazine.