In 1977, following the 1975 passage of the Energy Policy and Conservation Act (EPCA), almost all petroleum exports from the United States were banned. The Commerce department was allowed to make a few exceptions, such as for trade with neighbors Canada and Mexico. All this was, of course, in response to the OPEC oil embargo of 1973. The act also established the Strategic Petroleum Reserve and set up guidelines for energy conservation and further efforts toward reducing dependence on foreign oil.

In 1977, following the 1975 passage of the Energy Policy and Conservation Act (EPCA), almost all petroleum exports from the United States were banned. The Commerce department was allowed to make a few exceptions, such as for trade with neighbors Canada and Mexico. All this was, of course, in response to the OPEC oil embargo of 1973. The act also established the Strategic Petroleum Reserve and set up guidelines for energy conservation and further efforts toward reducing dependence on foreign oil.

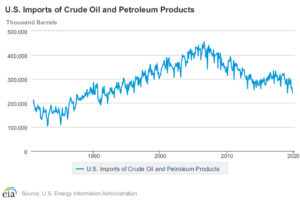

Having peaked in 1970 at 9.64 million barrels per day, U.S. oil production was slowly declining however, causing imports to rise over the years. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (USEIA), imports of crude oil and refined products peaked in August of 2006 at 455,000 barrels per month.

By 2015, the shale revolution had opened new basins, such as Texas’s Eagle Ford and North Dakota’s Bakken, was in the process of more than doubling production elsewhere, including the Permian Basin, and imports were dropping.

But there was a problem—after decades of importing heavier crude from OPEC and elsewhere, U.S. refineries were not set up to refine the light, sweet crude from most U.S. fields. So domestic production was stranded except for a few barrels swapped with Canada and Mexico, and the United States remained a net importer.

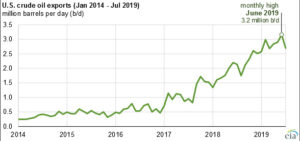

On December 16, 2015, President Obama signed into effect The Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2016, repealing section 113 of the EPCA, which had restricted exports.

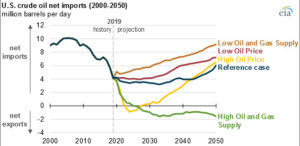

From the attached USEIA chart, it is clear that only a few months were required for this to begin dramatically changing the export landscape. As of the summer of 2019, the United States became a net exporter of oil and refined products, while still importing significant amounts of heavy crude.

https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=42795

https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=41553

Complex Markets

It sounds so simple: get the oil and gas to a port city, load it on ships and export it, make money. But those ships have to be headed toward buyers, prospects who’ve decided to buy from the United States instead of others clamoring to reach the same markets.

The late 2019 trade agreement with China, wherein the most populous nation on earth agreed to buy $18.5 billion in energy products in 2020, would seem to be a good start, if those numbers are reachable.

Even if they’re not, an open door and reduced tariffs would allow the United States to send more oil there in 2020 than has been possible before, says Enverus’s Senior Director of Crude Market Analytics, Jesse Mercer.

Returning to 2017 levels, before trade negotiations began, would only equal about $4 billion (around 220 MBbl/d), but it would be more than China has bought from the United States since 2017. “Increasing those volumes to around 500 MBbl/d would certainly go a long way toward meeting about half of that $18.5 billion goal, but that looks unlikely to happen given the extent to which Chinese refiners have had to cut runs due to the coronavirus outbreak’s impact on refined product demand in the country,” Mercer said in an email interview. “The $18.5 billion figure was a stretch to begin with before coronavirus hit, and the goal of $33.9 billion in 2021 is going to be an even tougher hurdle to clear.”

Along with trade agreement there are indications that China will grant tariff exemptions to qualified importers, reducing costs to refiners. These export opportunities are not likely to boost prices, Mercer feels, because they will only “displace spot cargos that were going to China from places like West Africa or Brazil. There’s just too much supply in the system right now.”

The two-year-long negotiations had unintended benefits, said Mercer. Trade with Europe expanded, and the number of destinations for U.S. oil increased as well. “The list of destinations has since grown to 42 countries [from 36 before the sanctions], of which nine consistently import over 100 MBbl/d. Five of those actually import more than China did on average in 2017.

Output changes from other producing countries—whether up due to new fields or down due to embargoes or unrest—also affect the supply/demand balance. “There has been an increase in waterborne supply from the new Johan Sverdrup field in the North Sea, the Liza field in Guyana, as well as continued growth in Brazilian offshore production.

“The cargo market would actually be a lot worse shape right now if not for the disruption to Libyan exports, which took about 1 MMBbl/d of light sweet off the market. Since U.S. Gulf Coast exports are predominately light sweets, any increase in Libyan production would likely reduce European demand for spot cargos from the United States.”

If U.S. refiners were to adapt more to the processing of lighter oil from domestic producers, there might be less oil to export, but less need to import as well. Mercer said refiners are thinking creatively in order to do just that, on at least a limited scale. They are importing greater amounts of other countries’ residuum, the “leftovers” from the processing of sour crude, to mix with light sweet in their process.

“This has been driven by the relatively high price of imported Middle Eastern grades, the sanctions the Trump Administration imposed on Venezuelan cargos, and the IMO2020 global spec change for marine fuels,” said Mercer.

“Marathon Petroleum, and Phillips 66 all reported increased domestic light sweet runs in 2019 vs. 2018.”

On the natural gas side, LNG export facilities are being built at breakneck speed, but what Enverus’s Rob McBride called Europe’s “winter that never was” has created a storage glut. This means that less gas will be needed during the summer, the traditional season for refilling storage facilities. Prices in late February were already reflecting this reality. Said Mc Bride, who is the company’s Senior Director –Strategy and Analytics, “We expect the global market to remain oversupplied into 2021.”

Port of Corpus Christi Becomes Export Hub

Ports on the Texas Gulf Coast have shouldered much of the export burden, with the Port of Corpus Christi leading the way. The more-developed Port of Houston is the center of refinery activity, with less room to grow exports, although exports have grown there as well.

Mercer noted, “Most U.S. crude exports leave through the ports of Corpus Christi, Houston, and the Nederland/Beaumont area. Considerable volumes also exit via the Seaway facility in Freeport, Texas, as well as the Louisiana Offshore Oil Port (LOOP).”

According to Sean Strawbridge, CEO at the Port of Corpus Christi Authority, “Crude exports represented about 46 percent of our total bulk movements in 2019.” Total liquid bulk movements include refined products, crude, and natural gas liquids.

Strawbridge said 2019 was a record year for the POCC, its fourth in a row. “Our fourth quarter of 2019 was the best we’d ever had, December [2019] was the best month we’d ever had” as well as the year as a whole being a record. The year began with the port handling 700,000-800,000 barrels per day. “We ended 2019 averaging between 1.7 and 1.8 million barrels per day. We added another million barrels per day to the export market.”

The increased volume comes from new pipelines, including Cactus II, Epic, and Grey Oak, the latter of which goes to Valero’s Three Rivers refinery.

The increased volume comes from new pipelines, including Cactus II, Epic, and Grey Oak, the latter of which goes to Valero’s Three Rivers refinery.

As the state’s natural gas pipelines continue to expand, POCC’s liquefied natural gas (LNG) capacity has grown as well. “We have about 6 million tons of incremental LNG [capacity] in 2019 over 2018,” he said, explaining, “That was primarily a result of Chenier having their second train come online.”

Development continues at the port, with expansions of slips and of loading facilities, even as investment in upstream sectors has slowed. Strawbridge attributes at least part of POCC’s continued funding to the fact that they are a government agency.

“The Port Authority itself is a governmental agency, so we’ve got the good fortune of having access to public capital—and there’s been a demand for investment-grade municipal bonds. We issued some debt in 2018 that was significantly overly subscribed.”

Much of the bond money is earmarked for the deepening and widening of the POCC ship channel, a Federal project executed by the Army Corps of Engineers. The bonds were raised to cover the POCC portion of the cost.

Phase one of the four-phase project was being completed at the end of January. At that time the Corps of Engineers was reviewing bids submitted for the next phase.

Upon completion, “That will give the Port of Corpus Christi the deepest and widest draft channel on the U.S. Gulf,” said Strawbridge.

He does not see the Corpus Christi port competing with Houston’s larger and more established facility. “We do zero containers—that’s a badge of honor for us—there’s one major container port in Texas, it’s Houston. I firmly don’t believe that Texas ports compete with each other because we’re not in the container business, which is 70 percent of the Port of Houston’s business.” Neither does POCC aspire to reaching the refining capacity available in Houston, which is currently several times that of its southern neighbor. He sees Houston’s refineries making it a destination market, whereas POCC focuses on being a departure point for exports.

While the great majority of exports are waterborne, Mercer said some exports to Canada travel through pipelines.

“Also note that of the roughly 460 MBbl/d of U.S. crude exported to Canada last year, approximately 160 MBbl/d did so over land via Enbridge Line 9 [namely Bakken crude going to refineries in Ontario and Quebec]. The remaining 300 MBbl/d is exported to refineries in Eastern Canada via terminals on the U.S. Gulf Coast,” he said.

The United States also exports significant natural gas into Mexico, with 158,633 mm cubic feet traveling to Mexico by pipeline in November of 2019. A small amount of LNG also went to Mexico by truck.

Trade with Mexico additionally includes importing crude and returning refined products to Mexico.

With interconnected economies and technologies wrapping the globe ever more tightly, oil and gas markets reflect international events on an almost hourly basis. The supply chain is susceptible to numerous choke points, with supply/demand based commodity prices controlling the valves at those choke points.

The times, it seems, are as volatile as oil and gas themselves.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

By: Paul Wiseman