Geophysical companies work to expand opportunities in a challenging economy.

By Paul Wiseman

Every stratum of the seismic industry is struggling as the explosion of oil and gas production creates low price shock waves for the industry across the globe. The small privately-owned company that interprets and stores data, the publicly-owned geophysical firm and the multinational company that shoots and interprets data and manufactures the equipment used—they’re all facing earth-shaking staff reductions and looking for new ways to use seismic data in order to stay alive.

Low commodity prices are not the only challenge. Seismic companies were already fighting the idea that, in 90 years of collecting data, there’s no more to be learned—instead pointing out that, with new technologies and new ways to combine seismic with production data, producers can both drill and frac with greater accuracy than ever before. Plus, smaller companies in particular must battle rising overhead such as rent, healthcare costs, and more.

To the question of “Where do you see the seismic industry in five years?” answers ranged from a nervous laugh and “I hope we’re still here,” to “That’s a tough question.” To stay alive, a sector that has already morphed greatly in the last 20 years continues to seek ways to adapt.

The early 1990s saw the last seismic revolution with the development of 3-D, said Steve Jumper, chairman of the board, president, and CEO of Dawson Geophysical. “In 1994 the question we addressed more than anything else was at what point would we have it all shot,” he recalled. “That’s 21 years ago and [now] we’re back in the Basin.”

Keeping them in the Basin and elsewhere is the fact that data needs have changed along with changing production methods. Unconventional reservoir and microseismic monitoring of the hydraulic fracturing process are two significant developments in that category.

“We can monitor and record hydraulic fractures during the process, and maybe get an understanding of what the frac actually did, where did it go,” Jumper said. “From a completion standpoint, we’re going from a lateral wellbore with a frac in it to, probably, stacked and/or staggered wellbores that’ll be a volume completion, not just a linear completion.” Passive seismic can be used to show if the frac went all the way through. Jumper sees this kind of tracking as something with growth potential.

The challenge in tracking a low-energy event—as opposed to one where the seismic trucks use machinery to create trackable waves—is to separate the signal from the noise. In other words, to separate vibrations from trucks and wind from the noise of the perf shot or from rocks breaking a few thousand feet underground.

Dawson is working with its equipment suppliers on how to position equipment and ways to focus the incoming energy in order for it to be recorded and interpreted. “It works better in the Eagle Ford,” Jumper said, “Eagle Ford rocks break pretty loudly. Out here, this rock doesn’t break quite as loudly.”

The Permian’s hard surface rock makes seismic data more difficult to interpret than that from many other places, including offshore, Eagle Ford, and elsewhere, agreed Debbie Lawrence, owner of Pinnacle Seismic Ltd. “We have too much hard rock on the surface out here, in a lot of places.”

Dawson focuses on acquiring data while Pinnacle does interpretation and data storage.

Lawrence also addressed the need for additional data for new production methods. “In the earlier days, before all the big stuff was found, they were looking [just] for big structures that are easy to see. Now when you get a dataset and see a big structure, you know somebody’s already drilled it.”

With new shale plays producers are looking for the properties of the rock, not just the formation itself. “They know where the oil is because the shale is a thick enough layer that they know where it’s at, but they want to guide the drill bit. To do that, they want to avoid small fractures, faulting, and things like that,” Lawrence continued.

Historically this information was difficult to see, but then it was not necessary with older production methods. New technology, spawned by the need, now lets geophysical companies “see” these fractures that would potentially channel oil flows away from the wellbore.

Jumper describes the benefits of seismic in unconventionals as “keeping the well path in the zone. Make sure there’s not a fault in the way, make sure you’ve got the structural dip in the right direction, mainly just geohazard assessment.”

Dawson is getting some of the additional data Lawrence referred to by adding additional channels and using multi-component recording. Now, in addition to recording the conventional compressional or primary waves—in which the rock particle motion is parallel to the direction of its propagation—the company is adding the shear component. Shear waves are perpendicular to the direction of propagation. Jumper described this as, “In a crude sense, the aftershock of an earthquake.”

The benefit is, “If you can start to understand the difference between how the compressional response varies, on a ratio standpoint, from the shear component, you can learn a little bit more about rock properties and I think there’s some real upside.”

Jumper compared the progress in seismic logging details over the years to moving from an X-Ray to a CT scan to, soon he hopes, an MRI and eventually an HD signal.

Additional details come from larger surveys—200-300 square miles instead of the 50 or so of previous eras—plus the additional number of channels recorded. In the late 90s, for example, “If we had 4,000 channels on a crew, that was a pretty good size crew. I think it’s not uncommon for us to be upwards of 15,000 now.” And 20,000 channel-shoots are becoming more common in some areas as well.

Even this use for seismic data was slow in coming—producers in resource plays did not at first see the need for new data, which made for lean times in the business. Fortunately, geographical expansion came along just in time in the early years of the new century.

Both companies found new business in gas plays since 2003—Pinnacle in Kansas and Dawson in the Ft. Worth area’s Barnett Shale. “About 40 percent of my business has come out of Kansas in the last few years,” said Lawrence. “That’s what saved me during the big boom here.” Then as the boom continued in the Permian Basin and producers saw the need for more data, business shifted back to the Basin in 2014—then the bust hit.

Dawson’s move to unconventional work began around 2004 with gas plays in the Barnett Shale, Woodford, Haynesville, and the Marcellus. “Up until the financial crisis of ’08-’09, we were natural gas-driven,” said Jumper.

By 2011 Dawson’s business came from liquids, but still on the unconventional side. “That took us back in the Permian, Eagle Ford, Bakken, Niobrara, Mississippi Lime, Mid-Continent, those types of regions.” In the last year, the Permian Basin, Delaware Basin, and northern Eagle Ford have been their bread and butter, with a smattering of business elsewhere. Jumper noted that their last significant business in the Barnett ended in 2007.

Yet another way to boost seismic data usage is to combine its predictive power with results from completed wells, making the data more robust in the future. “I think we can get a seat at the table as they begin to further integrate sciences—engineering, petrophysical, geological, add geophysical in there.”

By combining well logs and other information from completed wells of varying production rates with the seismic data, Jumper hopes to refine the understanding of seismic to make it a better predictor of a well’s production capacity. “Seismic information really becomes helpful when you have a base of information that you can integrate into seismic data,” he said. The more wells providing data in an area, the better producers can predict what happens in the next well nearby.

Would those improvements ever lead to finding oil itself rather than formations that likely hide it? Jumper said more technology is needed for onshore operations, but offshore it’s already happening. Joe Dryer, vice president of data licensing for Fairfield Nodal, agreed, noting that 4-D seismic offshore does locate changes in fluid properties of reservoirs, plus finding what the industry terms “bright spots” for gas plays.

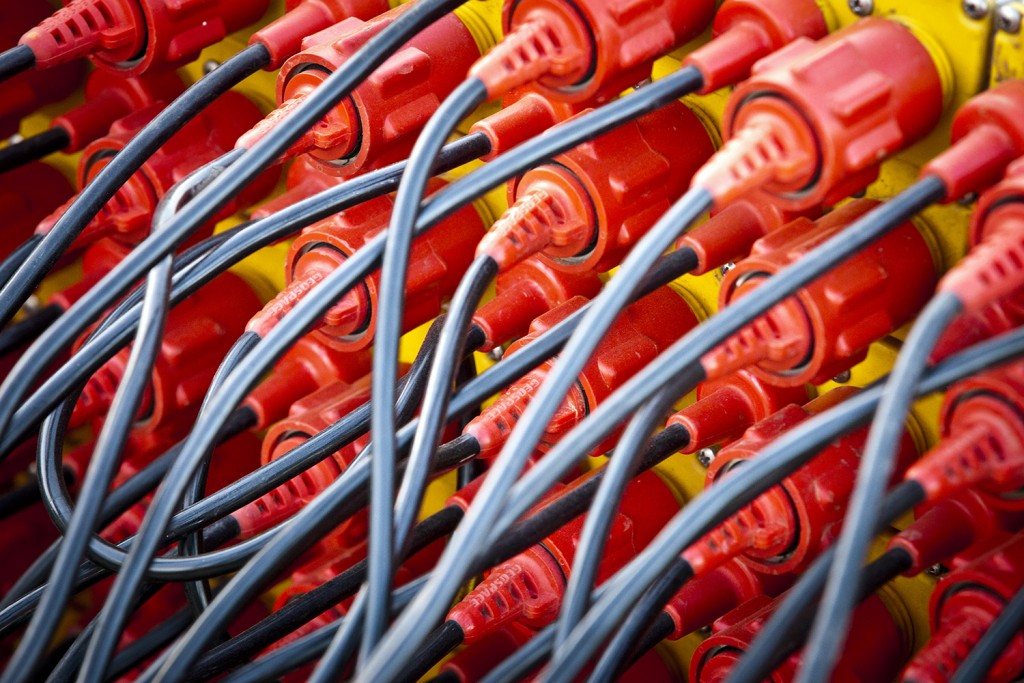

Whatever advancements in technology and equipment, both companies stressed the human factor. Lawrence noted that interpretation still requires the human eye and experience to extract its meaning. Jumper pointed out that the acquisition of data requires experienced field personnel to place all the equipment and record the data.

Houston-based Fairfield Nodal has its fingers in virtually all slices of the seismic pie, including acquisition, interpretation, and manufacturing of equipment. The company’s Joe Dryer, said Fairfield is addressing the downturn with reductions in costs and reductions in staffing—an issue Dawson and Pinnacle have also dealt with.

Fairfield, while active onshore only in the Delaware and some other Permian Basin locations, is finding its best business offshore in the Gulf of Mexico. “We’re busy doing field development surveys in deep water,” Dryer related. In the Basin, “We’re building a large regional dataset by overshooting existing data using new technology.” The new data will be better sampled with better resolution and better offsets, he stated, using more channels and wide-azimuth acquisition to accomplish this.

Regarding manufacturing, Dryer said the challenges involve heavy competition worldwide in addition to lower demand for equipment due to oil prices. He said Saudi Arabia is one of the few countries still using seismic data and equipment.

Over the last 20 years, the number of seismic companies has already fallen significantly, mostly due to mergers and acquisitions. While the current survivors continue to scan the horizon for more business, the economics are quite challenging. Lawrence acknowledged as much in saying, “In 18 years in the business, this is the worst I’ve seen.” Hopefully things will work out to where there are many more years in business for Lawrence and her cohorts.