Recollections of the old “Fort Worth Spudder” and other early-day portable drilling machines.

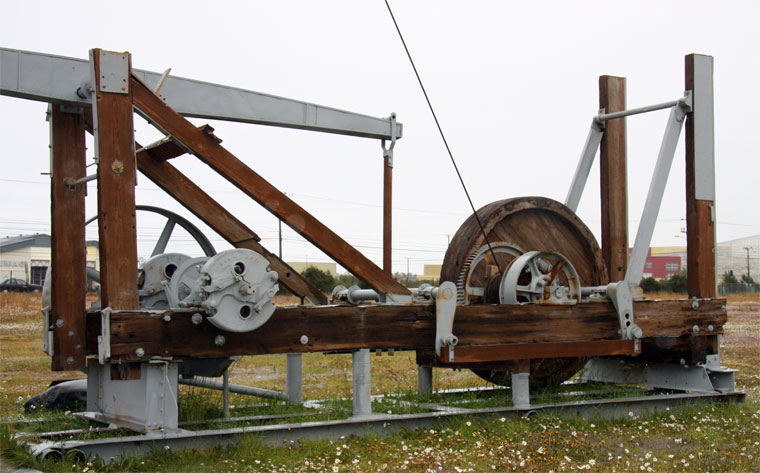

This photo shows what appears to be a stripped-down framework of an old Fort Worth Spudder. See other photos for comparison.

by Bobby Weaver

Probably the most recognizable imagery related to the oil field is a towering derrick. That was especially true in the early days of the industry, when it was not uncommon to see a veritable forest of those derricks clustered in a confined area, creating a sight that all-but-screamed “Oil field!” Such imagery evokes a common assumption dating from those times—the notion that oil wells were drilled only by what came to be called “standard” drilling rigs, having derricks whose tall superstructures were of a semi-permanent nature, which many times stayed in place after a well was completed. What is often overlooked is that a significant number of those early wells were drilled by portable drilling machines, units using either single- or double-pole masts that were folded down when they were moved. Their collapsible nature never lent them the dramatic visual impact of standard drilling rig derricks. Those machines were relatively efficient for drilling as long as well depth remained in the 1,500 to 2,000 foot range and most were suitable for use as workovers in wells up to 6,000 feet in depth.

From the very beginning of the oil and gas industry those portable cable tool drilling units played a significant role. Although developed in the 1870s and 1880s and used primarily for water well drilling, they experienced considerable modification and change over the years, an evolution that witnessed an increase in their drilling capabilities and overall efficiency. By the beginning of the 20th century they were being used throughout the oilfields in the United States.

Cable tool drilling machines are commonly called spudders, although that term is somewhat misleading unless you have some understanding of the machine’s early use. That name developed in the early days when, in order to start a well, a guide pipe was set in the ground to keep the drill bit vertically oriented at the beginning of the drilling process. In the very earliest times putting that pipe in place was accomplished by digging a cellar and setting the guide pipe in by hand. Later that labor-intensive process was abandoned in favor of using the drilling machine itself to actually pound the guide pipe into the ground. The bit used to drive that guide pipe was a blunt-ended drilling device called a spud bit. Because of that process, those drilling machines came to be called “spudders” and from it developed the term “spudding,” or “spudding in,” to identify the beginning process of drilling an oil well. Today, well over 100 years later, the term “spudding in” like so many other oil field terms, has transcended its lowly beginnings and is still used in the oil patch to signify the beginning of the drilling process on a well.

All manufacturers of those machines produced several models, ranging from lightweight machines capable of drilling only a few hundred feet and used to drill water wells to larger models, some of which were rated for as much as 4,000 feet, although the larger ones were rarely used because of weight considerations. In those areas where oil wells stayed in the 2,000-foot range or less, drilling machines were extremely popular both for drilling and running casing. Using them negated the need to employ expensive rig building crews and all the transport problems associated with moving men and construction materials to drill sites. Some were self propelled, but most were towed to the well site by teams of horses or in later times by track-type tractors. In the early days spudders were all steam powered, but by the 1920s just as was the case with the standard drilling rigs, a significant number became powered by internal combustion engines.

There were a number of manufacturers of those drilling machines, but only a few models became widely used. The first practical machine was invented by R.M. Downie in 1879 as a water well drilling device and was manufactured in Pittsburgh under the name Keystone. After a few years Downie moved the operation to Beaver Falls, Pa., where he established the Keystone Driller Company, which over the next decade or so instituted a number of innovations that made their machine suitable for oilfield use—including the step of introducing hard rubber wheels. After internal combustion engines were available in the early 1920s, they introduced some units with crawler-track tractor wheels. Keystone remained among the leaders in portable drilling machines until the 1940s, when the company was dissolved.

By the 1890s the National Supply Company had introduced a skid-mounted drilling machine, though with later models they changed to a wheel-mounted design. The National was advertised as, “The rig that displaced the old standard derrick.” The National played an important role in oil well drilling at least through the 1930s. Along with Keystone, these two makers were part of a large field of nationally known drilling machine companies. In the early days their brands included well known names such as Parkersburg, Columbia, Wolfe, Leidecker, and Buycrus-Erie. There were a host of lesser-known drilling machines whose markets were restricted to the immediate areas where they were built. Meanwhile, yet other, lesser-known lines—makers of machines that were, for all practical purposes, homemade devices—have left little record of their existence beyond a bare mention in local histories.

Beginning in the 1890s and continuing until after WWII, perhaps the most widely used drilling machines in the oil patch were manufactured by the Star Drilling Machine Company of Akron, Ohio. That company boasted that their Akron facility was, “The largest factory in the world manufacturing only portable drilling machines.” They even claimed that, “Ninety-five percent of all oil wells in the world drilled by portable machines were drilled by Star Drilling Machines.” That advertising hyperbole aside, the Star does appear to have been universally popular throughout the oil patch and probably dominated the market.

The machine best remembered in West Texas, particularly in the 1930s through the 1950s, was the Fort Worth Spudder, manufactured by the Fort Worth Machinery and Supply Company of Texas. By 1935 they offered eight sizes of machines capable of drilling from 200 to several thousand feet. Five of those models were heavy duty portable units specifically designed for oilfield use. Their Jumbo J model machine was even advertised as being capable of drilling to a depth of 6,000 feet.

The first documented use of a portable drilling machine in the Permian Basin occurred on January 8, 1921, in association with the Santa Rita #1, whose completion set off the activity that ultimately produced the Permian Basin oil field. Frank Pickrell, who was trying to keep possession of his lease on the Santa Rita property, was running out of time to show good faith on beginning work on the well. Not even having rig builders on the site and with only a couple of days left to begin drilling, he had a portable rig brought in, began drilling a water well to supply the proposed drilling site, and found two passing cowboys to sign an affidavit that drilling was taking place. The ploy worked and more than two years later, using a standard drilling rig, the well was completed at a depth of 3,050 feet and the boom was on. So it could be argued that the Permian Basin discovery well would not have happened without the help of one of those portable drilling machines.

The beginning of Permian Basin activity coincided almost exactly with the changeover to gasoline-powered drilling machines. Because water was critical to the operation of the steam powered machines and the Permian Basin was an arid to a semi-arid region where water was at a premium, equipment that didn’t need excessive amounts of water had an decided advantage. The problem was that almost all the wells were in excess of 3,000 feet, which was at the limit for most of those portable units. Nevertheless, hundreds of those drilling machines were used mostly to drill water wells and to a lesser extent to drill producing wells in areas where the depths ranged in the 2,000 foot category.

There was one major exception to that rule. The Yates field in an isolated region in southeastern Pecos County was discovered in late 1926 and reached flush production in 1929 to became one of the most prolific oilfields of that era, with more than 500 producing wells. One of its wells came in at more than 8,000 barrels and many flowed in the 3,000-barrel range. Most of the early wells in the Yates were drilled at a cost of less than $15,000 each. The low drilling costs can be attributed to a combination of factors: the well depths were in the relatively shallow 1,200- to 1,500-foot range and practically all of them were drilled with portable drilling machines, whose cost of operation was very low.

During the 1930s well depth in the Permian Basin gradually became much greater, which caused cable tool drilling to give way to rotary rigs. During that same time period the portable cable tool machines became more and more obsolete, although they continued to do some in-fill drilling in the older fields and many were converted to well servicing type activities. By the post-WWII era they were mostly an out-of-date curiosity of the past. Today the best and most complete representation of those mostly forgotten pieces of oilfield technology can be found in the outdoor exhibits at the Permian Basin Petroleum Museum at Midland, Texas, where curators have done a remarkable job of preserving those important elements of oilfield history.

Bobby Weaver writes regular for Permian Basin Oil and Gas Magazine. His humor column, Oil Patch Tales (see page tktktktk), appears in every issue.