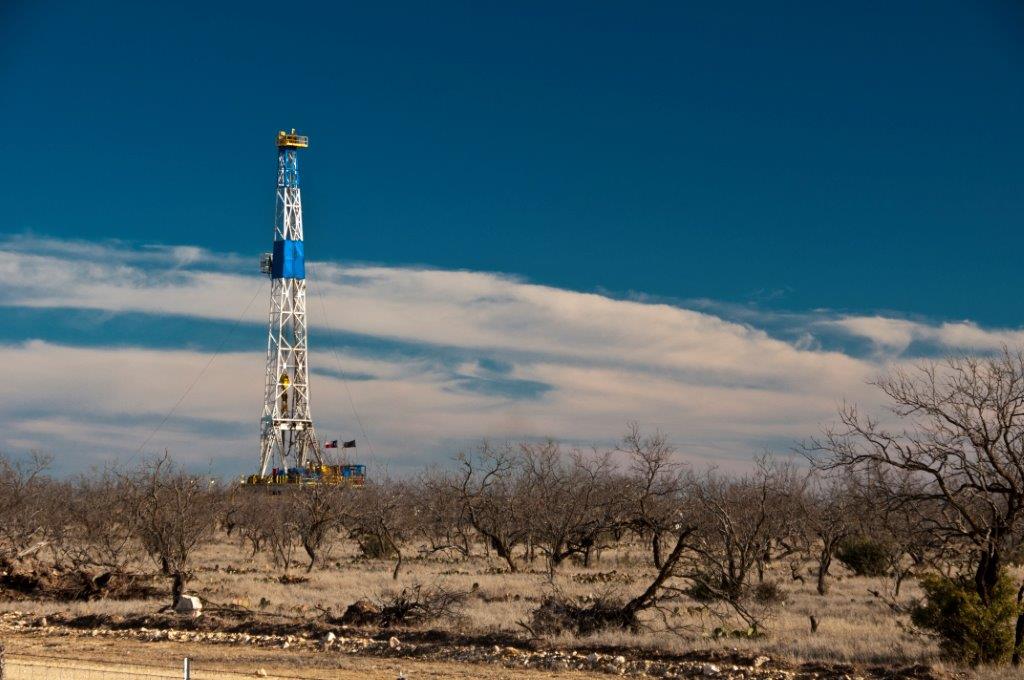

J. Ross Craft, chairman and CEO of Approach Resources, has a career that is intertwined with the storied “career” of the Wolfcamp play. Like Jim Henry before him, who pioneered the Wolfcamp vertical shale play, Craft and his contemporaries have made some “lateral” moves that have changed the landscape.

by Jesse Mullins

Permian

Pure and Simple

That pretty much sums up Approach Resources today. Its founder, J. Ross Craft, has overseen oil and gas operations in locales as farflung as Tunisia, but from the early 2000s he and his teams were already in the Permian Basin—even before it was known as an “unconventional shale play”—and it is here in the Permian Basin that he and Approach Resources have concentrated their efforts and made themselves the striking success that they are.

Approach Resources—now a public company, traded on the Nasdaq (it wasn’t always public)—currently has 138,000 gross acres in the Basin. Approach employs 100 people, with about 60 of them employed in the company’s field office in Ozona, and the rest of them employed in the headquarters in Fort Worth.

Craft, an engineer by background, has more than 30 years’ experience in the oil and gas industry. A graduate of Texas A&M, he is a member of both the Permian Basin Petroleum Association and the Texas Oil and Gas Association. In 2012 he was a regional winner of the Ernst and Young Entrepreneur of the Year Award.

It hasn’t always been this sunny for Approach. With the onset of the recession of 2009, the company hit a rough stretch.

“When gas prices collapsed in 2009, I shut all my rigs down,” Craft says. “I didn’t have to drill, I wasn’t going to drill. And it wasn’t a good business decision to continue to drill in a bad environment. I had seven rigs working. I shut them down. Wall Street hated me for it. I mean, Wall Street crucified me—our stock fell quite a bit. But at the same time, I paid off about $30 million in debt that year. And at the same time, I started working on the Wolfcamp, because I knew I had to do something different. [Approach had previously been drilling wells in the Canyon gas play, and those deep gas wells lay in a zone beneath the Wolfcamp.] And so we started working on the Wolfcamp, I guess in 2009, about the same time EOG, our partner, our next-door neighbors out here, started working on their play in the Wolfcamp. And so they drilled the first two horizontal Wolfcamp wells, and I think we drilled the third or fourth one. And in 2010, I think it was October 2010, we were the first company to present the Wolfcamp to Wall Street in New York in a big analyst presentation that we hosted. And so, it was quite interesting back then, because Wolfcamp was a ‘concept,’ but at the same time, we were looking at it from a reserve standpoint, and from the large areal extents, and [had decided that] this thing is world-class. We had already pretty much refined the completion process to where we knew that it would work. We just had to continue to work on it to get the well costs down and the EURs up.”

Since then, it’s been better and better.

Craft is someone with a plenitude of common sense, according to Kirk Cleere, CEO of Sendero Drilling, which has offices in San Angelo and Midland. Sendero has drilled many wells for Approach Resources. And Cleere, working in other, former capacities, has drilled a multitude of wells for Craft, when Craft worked in other, former capacities as well.

Cleere, speaking by phone from San Angelo, said that just hearing the name Ross Craft, “made me smile.”

“I think the world of Ross Craft,” said Cleere. “Always have. I’ve been working for him ever since back in the early 1990s. One thing Ross has always had is great practical knowledge. There are a lot of guys out there who are brilliant in book knowledge. There are a lot of engineers who were great students. What’s different about Ross is that he understood the field operations and could actually take that technical data and put it to work in a common sense application.

“A lot of engineers are really smart but the thing I think is neat about Ross is—especially when it comes to frac’ing—like when he made a career out of the tight sands in the Canyon Sands play, whether with vertical or horizontal wells—he not only understood the technical angles, where frac’ing is concerned—the process or the frac fluids, for instance—but he also understood the geology.

“On top of that, he is, from the business perspective, extremely honorable. And loyal. He is good with contracts, etc., but the thing is, you could do anything you wanted to with him on a handshake. Extremely honorable. For him, a deal is a deal.”

The deals are done in Fort Worth, where Approach is headquartered, and where Ross and his wife of 30 years, Donna, have been all along. They have one son, Corbin, who currently attends Abilene Christian University.

This iteration of Approach Resources is the third company Ross Craft has started.

“After we sold American Cometra [Craft was with that company in the ’90s], the president of American Cometra and I formed a company in 1997 called Athanor Resources,” Craft said. “It was an international company with operations in North Africa and West Texas. Kind of a mixed bag. So we sold that company in 2002, and then the same financial backers that backed me in Athanor formed Approach One in 2002. Eventually West Texas oriented—looking for tight gas plays at that time, in the Ozona and Crockett County area. We picked up quite a bit of acreage and drilled quite a few vertical wells, obviously. Probably close to 600 vertical wells in that period of time, up through probably 2009. And that’s when the gas prices pretty much started collapsing on everybody.”

Craft went public with the business in 2007. “We were going to sell Approach One. And then we formed Approach Two, piggybacking off of that. And then because of market conditions and such, we decided not to sell either one and roll it into a public company. So we did, we went public in 2007 and then we went through that little downturn. But the beauty about it was, we had a lot of this acreage in Canyon Gas, and we made a major discovery in the Canyon field that everybody forgot about. Nobody knew it was there. This was in about 2006. It was a 50 million BOE discovery. But the interesting thing about this acreage is that, since the Canyon’s deeper than the Wolfcamp, was that there were airholes and I was taking logs and had mud loggers on these airholes, which nobody did, and that’s when I started seeing the Wolfcamp shows. And that was back in 2006, 2007, 2008, and I really didn’t pay much attention to it because I looked at it and I saw that it was a big shale zone. But it was interesting, because I got some really robust shows out of it.”

This was all in the Canyon tight gas sands play. The Canyon was prevalent throughout Sutton County and Crockett County and up into Irion County.

“Our first three [Wolfcamp] wells weren’t very good,” Craft says. “But then we started figuring out how to do it, and the best way to do it. Meanwhile, a company called Broad Oak Energy drilled a horizontal Wolfcamp well about the same time as EOG and Approach. So that’s kind of where the play kicked off in the Southern Midland Basin, down in the northern Crockett, Irion County area. And the rest is pretty much history. We started drilling and commercializing the play; we were the first ones to commercialize all three zones: A, B, and C. A lot of the nomenclature being used in the Wolfcamp is what we developed back in 2009, and since that point, I think we’ve got close to 189 horizontal wells online. In the southern part of the basin, where the play kicked off, there’s got to be 2,000 horizontal wells, maybe more.

“The thickest portion of the play in the southern part of the [Midland] Basin, and then it gets thinner as it moves to the north but it also gets deeper, and that’s why it holds more oil, and it holds in longer than to the south.

Asked how this history affects the way that Approach operates now, Craft turns to the “Pure Permian Play” concept.

“Well, obviously, before we found the Wolfcamp and started devoting everything to the Wolfcamp, we had plays all over the place. We had some acreage up in British Columbia, we had some stuff in Kentucky, some stuff in New Mexico. These were all exploration plays. Plus the Canyon play down here and some East Texas assets. Since the Wolfcamp developed, we’ve now started full-time development of Wolfcamp, and we basically sold all the other assets and devoted all of our capital to developing the Wolfcamp.”

SWITCH to third tape:

Of course, the downturn of 2014-16 hit Approach like it hit everyone else.

“This downturn has not been friendly to Approach,”Craft says. “There’s no question about it. You know, we’ve had to pull back in and work on our balance sheet, which we have done. We reduced our debt in ’17 by roughly $127 million, and we had to do that so we could be competitive again.”

Which leads us to what is, for Craft, the best advice he can offer, where the oil business is concerned.

“The best advice I could give anybody is go at your own speed,” Craft says. “Don’t let Wall Street dictate what you do. Wall Street, back when we went public, was ‘growth at any cost.’ Our stock went as high as almost $40 a share, but it was growth at any cost. They didn’t care what you spent as long as you could show growth in your production. IPs [initial production figures] were the thing. And from the start, I told everybody in conferences, such as when I spoke at the DUG Conference, that IPs mean nothing.”

He pauses.

“Well, you know, we made the mistake,” he says. “We tried to do what Wall Street wanted us to. In 2014 we had a $400 million budget. That was the wrong thing to do. That’s what I spent the next three years since ’14 trying to do—to reduce that—because we took some high yield out, and we shouldn’t have done that. We should have just slowed it down. The key is to get into a play, but go at a pace that can be supported by the cash flow. It’s all right to take on debt, but take on debt in a very, very controlled manner. You know, there’s been over 100 bankruptcies, 100 companies that have filed for bankruptcy, and maybe more, since this downturn in the energy sector.

“It’s all because they got ahead of their skis, over their skis with debt,” he concluded. “Debt will kill you, so just go at your own pace. Develop what you can the best you can, and things will work good. It will work out for you. Don’t try to let somebody dictate how fast you need to go, because that’s not the way to do it.”

The Serendipitous Wolfcamp

PBOG: How fortunate is it for Approach that when this whole thing happened—this shale revolution—you were in the Permian. You had a position here and in a great place.

Craft: Yeah, it was fortunate and hyou known nobody really thought about the Wolfcamp. They knew from a long time back that it was a source rock. In our particular area of the Basin, in the southern part of the basin, it’s 1,200 feet thick, of pay. But nobody really could figure out how to unlock it, nor were they really looking at that. So, luckily, it was George Mitchell on the Barnett Shale, basically, who said, “Hey, not only can you frac it and make money at it, but it’s a world class resource play.” Then, as we all know, shale [development] went [into] several different plays and then the Midland Basin started popping off. And that’s where we really got interested, because we knew it had so much hydrocarbons in it because of the thickness and that it was something that would be world class at some point. We started playing around with it and luckily for us, the acreage that we had picked up for a completely different play, was in the right position.

PBOG: But you were into that area for gas wells, right?

Craft: Yes. Because of drilling the deeper gas wells, we were able, starting in 2002, 2003, 2004, to collect a lot of good data on the Wolfcamp. Even though at the time, we didn’t know what it really meant. At the time we were collecting this data—and I’m a data freak anyway, that’s my petroleum engineering background—I said, “Well, let’s try this.” So we played around with it, but it wasn’t until the gas price collapsed in 2008 and that financial meltdown came in 2008 and 2009, that we made a wholehearted attempt at trying to put this together and figure out what’s the best way. Can it be frac’ed? Can it be produced and all that? We came back and yes, it can.

I still remember the first well we tried and it wasn’t very good. We were using gel on it, gel fracs. The second well was a gel frac and it wasn’t very good. I’d joke around with people, and I’d say, “You know, our first few wells that we spent probably close to $17 million on didn’t even make enough grease to grease a tricycle.” But I knew I had to have something because our market cap at the time was only $160 million, so this was a big deal for us. Then we started playing around with the slick water frac concept, doing what they had been doing in other plays, and that’s when we really turned the corner on these wells.

Craft on Cost Containment

PBOG: Based on what you’ve said about your company’s evolution, getting your costs down has been an important step. Can you comment?

Craft: Yes. What’s interesting was when we first started drilling out here, the well costs were running about eight-and-a-half million a well. At the time, we were looking at somewhere around 350,000 BOEs of production. That was back in 2010, and we knew right there that that wasn’t going to be sustainable. So we had to get our well costs down, and we had to figure out ways to get the reserves up. So we started working on getting the well costs down. I think in 2014 we were down around $5.5 million per well. We had raised the EUR type curve up to about 510 MBOEs per well.

Then we started looking at ways to further reduce the costs. Actually, let me digress a little bit. In 2012 we started looking at part of our cost reduction to get to the $5.5 million a well, and we basically said, “Well, here’s the biggest chunk of our cost, and it’s frac’ing, it’s water handling, it’s water movement, and oil takeaways, and things like that.” So, we designed and invested into a major infrastructure program because the acreage was all contiguous.

With it being all right there together, contiguous, it allowed us to build this large infrastructure system on which we spent close to $100 million. We have our own gathering system for gas, for oil. We have a water system that brings produced water in to a central facility and then it takes frac water out and redelivers to the well site, both produced water and low chloride water. Plus we have a gas lift system that goes to every well, so everything’s on gas lift and—that right there—that alone saved us about a million dollars a well by doing this. And not only that, but it’s also reduced our operating cost considerably. Right now our operating cost is one of the lowest operating cost out here.

PBOG: And you had some success with takeaway, too, correct?

Craft: Yes. We also, in 2013, because there wasn’t much oil takeaway out of the southern part of the Basin, it was all a gas play before, so we were getting hammered on trucking differentials. Trucking differentials to get your oil up to Cushing was running about $10 a barrel. So I was sitting there at dinner one night [doing some figures, writing on an envelope] and I saw I could build a pipeline up to the Plains facility, the Owens Facility, 38 miles from here and that it would only cost me X, and I can deliver my production through my own pipeline.

So we started working on the design of it. It wasn’t going to be very expensive and the beauty about that, it was going across mostly University land so we knew we could get the right-of-ways. Then I said, “Well, let me get a small third party midstream company to slide in here and I will give them the design, and they can build it and operate it, and they can have 50 percent and I’ll keep 50 percent.” So we built this oil system, and then probably within a year and a half after building it, we flipped it for 6X return and kept the transportation rights on it. So that was a pretty good deal for us back then.

PBOG: So, you decided to become proactive in getting the oil takeaway…

Craft: Yes. We were the first ones to do it out here. A lot of people thought we were nuts, and we said, “No, this is the way to do it,” because we had already proven the play and we knew the play had this huge amount of resource potential. So we said, “Now let’s start cutting the cost.” And so, by us installing the system in 2012, and finishing it in ’13, we had the same corridors to every future well, we have this pipeline right-of-way that’s got six different lines in, buried. We’ve got three 8″ water lines, we have an 8″ low pressure oil line, an 8″ low pressure gas gathering line, and then we have an 8″ high pressure gas line for gas lift. So that has dramatically reduced the cost of the wells—even to a point where our wells we drilled in 2017 were $4.3 million a well.

PBOG: It’s like oil companies just have to think differently today.

Craft: Yeah, you have to think outside the box because there’s only two ways to change the rate of return of a well. You either can improve the reserves or you can decrease the cost. Or hopefully, you can do both, and we have done both. We just announced recently that our type curve increased from 510 MBOE to 700 MBOE per well, which is a 30 percent jump in type curve. And that’s just based on completions and what we’ve learned about that. But even more interesting was that we started looking at the frac’ water reuse concept and in cleaning produced water up and using it. We started working on that project in 2014. We were the first company to build a large water recycling facility. Actually, we got the Bruno Hanson Environmental Award for it. It’s a 320,000-barrel-storage, above-ground facility where we can process 40,000 barrels of produced water per day.