Straight Down or to the Side? Operators and drillers venture opinions on the place of verticals in a world gone heavily horizontal.

By Hanaba Munn Welch

A vertical well is a vertical well. Directional wells represent a broader category—essentially all wells that aren’t simply vertical, including wells that feature horizontal legs.

Technological advances have enabled drilling to follow all sorts of trajectories with precision. The future may hold spaghetti loops. Compared to all the variations, conventional vertical drilling can seem—for lack of a better word—boring.

But even though the ratio of vertical wells to horizontals has been steadily shifting toward a preponderance of horizontals—at least in Texas, where percentages based on completions have been changing by four to eight percent a year—a year’s worth of vertical completions still outnumbered horizontals at the end of 2014. By the end of 2015, year-end totals may tell a different story.

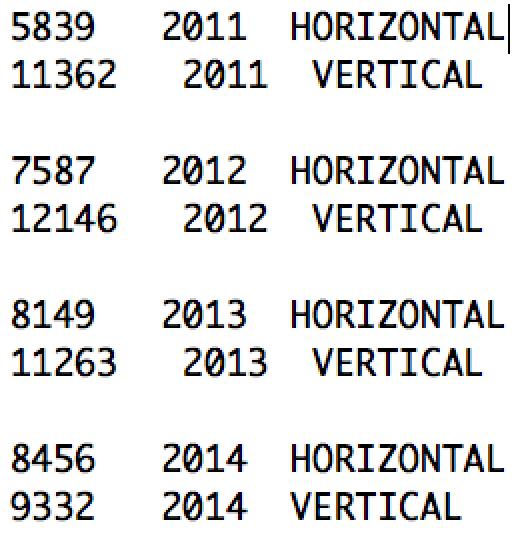

Texas Railroad Commission records for wells completed in Texas from 2011 through 2014 illustrate the trend:

In 2011, horizontal wells represented 34 percent of completions. By 2014, that percentage had increased to 48 percent. Horizontal wells are on track to surpass verticals by the end of this year.

But, if oil prices remain low, could the sheer expense of drilling horizontals affect the trend toward drilling them?

“They’re so damned expensive,” said Johnny Mulloy, Midland-based drilling consultant, weighing in on the topic. Sometimes verticals are a more cost-effective way to achieve production, Mulloy said.

“What you’re looking for is exposure to the reservoir,” Mulloy said. “If you can get exposure on four cheap vertical wells that you can get from one or two horizontal wells, that may be the way you want to go.”

But, as Mulloy and others of his ilk understand, cost-benefit ratios differ depending on various factors. A 1960 graduate of Texas Tech University in petroleum engineering, Mulloy has seen horizontals make their mark over time. In some cases, verticals make way for horizontal drilling. Mulloy remembers his first horizontal drilling experience. “The very first horizontal work I did, it’s been a good many years ago, it was for Texaco before the Texaco-Chevron merger.”

The location was near Levelland in the Slaughter Field. “We cut a window in them [the existing wells],” he said. From that point, the drilling proceeded horizontally. “I don’t remember how many feet,” Mulloy said, estimating the horizontal trajectories were from 1,200 to 1,500 feet.

The proverbial oilfield water can is worth a laugh amid the banter at Crescent Supply Co. in Abilene. “If you ever drink out of that water can, it’s like cocaine,” said customer Derrell Riggan, right, referring to the addictive nature of working in the oil industry. “You can’t get off of it,” said Scott Tarpley, Crescent manager. “You’re done.” Behind the counter is Rickey Weaver, assistant manager. Riggan owns DWR Oil Co. in Merkel. PHOTO BY HANABA MUNN WELCH

The strategy worked, enabling the recovery of virgin oil from the formation in areas between the previously drilled verticals. “It was cheaper because you already had the vertical wells there to work with,” he said. “It was a re-entry, so to speak.”

Sometimes a vertical well can provide information to let an operator know whether a horizontal trajectory would be a feasible undertaking for a zone in question. Mulloy, based on his years of consulting, wouldn’t advise horizontal drilling in areas where information is scant.

“In a wildcat area you would be very foolish to drill a horizontal well,” he said.

Derrell Riggan of Merkel would agree with Mulloy. Riggan owns DWR Oil Co.

“This is wildcat country,” he said, talking about his home turf in more than one direction from Abilene (Merkel is a suburb of Abilene). Vertical wells are the rule and horizontals the exception.

“We went and staked one [a vertical] today on the Guitar Ranch in Callahan County,” Riggan said. “These little shallow zones, that’s the only way you can make it profitable.”

Riggan is no stranger to profitability. Verticals wells have been good to him, particularly the time he drilled 80 in a row before he put a dry hole on the map. “We found the Clear Fork,” he said, referring to the formation. “We drilled about 80 or 90 wells.”

Now that prices are down—not just for oil but also for drilling and even for pipe—a vertical prospect is more affordable than ever. “You can get these wells drilled for $14 to $15 a foot,” he said. “They were $24 to $25.”

But the rewards are less too, meaning less incentive for anyone to take advantage of cheaper prices.

Riggan himself has lived long enough to see good times and lean times in the oil field. And tragedy. “My dad got killed on a drilling rig in ’81,” he said.

But it’s his way of life. “I started out roughnecking on a rig when I was probably 16 or 17,” he said. “We’d cut class and go roughneck.”

Earning $50 to replace a hand who didn’t show up was big money to a teenager. Riggan was hooked. He tried college, attending McMurry University on a track scholarship. His event was the high jump, and he won the conference his freshman year. “One year of college was all I could make it,” he said. “My buddies had new cars [ostensibly from money they were earning in the oilfield]. I had one that wouldn’t run.”

One new drilling location already staked for the day, Derrell Riggan relaxes at mid-day in late July at the break table at Crescent Supply Co. in Abilene. Taking a call from a Crescent service crew is Scott Tarpley, manager.

It was back to the rigs for Riggan. “Once you’ve drunk out of that water can, it’s like cocaine,” he said.

His friend Scott Tarpley, also of Merkel, grinned and agreed with him about the addictive nature of the oil business and picked up on the water can theme. “You’re done,” Tarpley said. “You can’t get off of it.”

Tarpley manages Crescent Supply Co. in Abilene, an oilfield equipment business. He even sells water cans, albeit the orange plastic kind. The business is a place where stories flow like oil. “This is kind of an oilfield beauty shop here,” he quipped. “One of the places where the lies get started.”

But Tarpley didn’t have time to tell many the day Riggan dropped by. His phone kept ringing. Cellphone to his ear, he told a hand how to deal with a heavy piece of equipment. “We’ve got no way to get a forklift out there,” he told the caller.

The service side of the Crescent operation is still fairly busy despite the slump in the industry, he said. “Knock on wood,” Tarpley said. “We’re not as busy as we were, but we’re keeping our heads above water.”

Along with other supplies and equipment, pumping units are part of the inventory. Most Tarpley sells are for vertical wells, he said. “In Abilene, it’s still a vertical business,” he said.

Riggan considers horizontal drilling a possible way to enhance some existing vertical production. “Chances are we could drill horizontal in Canyon sands,” he said.

To accommodate possible future horizontal drilling, Riggan runs eight-inch casing instead of five-inch in vertical wells that he believes might be worth enhancing laterally. Riggan obviously believes in being ready for change. But he conjectures it will arrive later rather than sooner in his part of the oilfield world. “We’re the last to get the technology,” he said. “You’ve got to get the economics down to where it will work around here.”

And as long as the price of oil remains low, the incentive to develop oilfield technology is less. For lack of options, conventional methods tend to remain in place by default.

As the slump continues to affect exploration, even the plugging of wells is affected—down by some reports.

“It’s slowed way down,” said Chuck Cassey, who works for DJ&T Services out of Abilene. “Nobody wants to spend the money. People that are plugging are the ones that absolutely have to.”

To plug or to drill or to do neither? Such questions always seem easier to answer when times are booming. And they’re not.

Freelance writer Hanaba Munn Welch writes regularly for PBOG. She maintains a website at www.hanaba.net.