On April 20, 2020, the benchmark price of oil—WTI—fell to an unprecedented level of -$37.61 for May 2020 futures contracts. While this event was not on the level of the invasion of Normandy or the release of the next iPhone version, its shock waves ripped through oil and gas boardrooms around the world—mostly because it was the blackest of black swans. No one had seen this before, nor had they seen this one coming.

There are varying opinions as to whether this event was truly significant. Only a few barrels changed hands at that price on paper, and probably no actual barrels. The situation only lasted one day, and nothing like it happened to Brent Crude or other benchmark oils.

As with most major events, the causes were more than meets the eye. Because of that there are varying opinions on how it happened and what the markets learned. Certainly, the demand drop caused by Coronavirus stay-at-home orders was the main driver, but there were other factors as well. Here, three experts look back at the event, its significance, and its aftermath.

Trisha Curtis is CEO of PetroNerds, an oil and gas consulting firm. She sees the exact event as less significant than what happened around it.

“I think the price going negative is a bit of a double dip—it’s sort of important and non-important. Prices could have gone to zero or gone to a dollar and it probably would’ve had the same jarring effect. But the fact that it technically went negative is obviously a big deal.

“But the volumes [at that price] were very small.” CME Group, a leading exchange organization that handles futures trading in oil and gas and other derivatives, had changed its rules, allowing negative trading, the weekend before the crash, Curtis said. “So people who held those contracts didn’t buy this knowing that, technically, the contracts could actually go negative—at least some of them didn’t.”

She related that only about 6 million barrels were involved in the negative trades.

It is significant to note that only WTI suffered that crash, “and that tells you a lot. Remember, Brent didn’t go negative. That’s [just] trading.”

So what caused it in the United States? Prices had already been sliding since the first days of 2020 because, she said, those prices were too high at that point, around $60 per barrel, compared to the fundamentals of supply and demand. “They weren’t hot because demand was elevated, they were hot because we had those Saudi outages and there were supply issues that happened in January.”

But, she said, “Ultimately, fundamentals win the day.” The slide actually began in February, before COVID-19 quarantines and travel bans took effect.

Over the previous five years including February of 2020, the WTI price had averaged $53 per barrel. So with the prelude to the pandemic revolving around a belief in stable oil prices, “then you drop so dramatically from there, that has a lot to do with how people responded to the dramatic impact” of crude inventory suddenly skyrocketing.

As those prices slid, the market share battle between Saudi and Russian oil suppliers began to heat up, and, Curtis said, “They did not understand what was going on.” They gravely miscalculated in their decisions to flood the market just as demand was crashing worldwide. “To be fair, this is something they maybe should’ve thought about, but it was a Black Swan they couldn’t have really predicted. They never would have done it [flooded the market with crude] if they’d understood that demand was going to come down 30 million barrels per day and put them in a devastating situation.”

What happened in the United States was more nuanced, and less reported in the news. Operators here quickly realized that there was nowhere to sell their production. “That was what caused the fear, and the prices going negative. It was that storage was filling up so fast that you couldn’t move barrels of oil,” she said.

Even though storage never actually filled up, she pointed out that the approach of such a status was enough to trigger a price collapse. There was also the fact that most pipelines were full—some were actually being used for storage—so even if Cushing or elsewhere had room for crude, there would be no way to get it there.

“The idea that it went to -$37 and back up within a day—nothing changed within a day to actually reflect that. That was not fundamentals, that was trading.”

Raoul LeBlanc, vice president of North American Onshore for IHS Markit, agrees with Curtis that the price drop was caused by market factors instead of fundamentals, and that surrounding events were more significant than the negative price itself.

Speculators had bought oil futures on paper that they wanted to sell—at a profit—before having to take physical delivery. Speculators do not have actual tanks in which to store oil. Those contracts were expiring, LeBlanc pointed out, so they had to get rid of them in a panic.

This affected only a few players, but some of them lost some serious money. “While the overall downdraft in oil prices was a real factor, that was a sideshow based on futures dynamics and somebody getting caught out,” he said. While it created headlines, the negative price wasn’t the story.

“The story really was what happened the next week or so, when you had prices sustained below $10. Negative prices don’t make any sense for any period of time, and they’re a fluke.”

As prices stayed below $10 in actual field sales, “That was the pain.” Because those prices were ongoing, not just for one day on paper, “Those were the prices people actually had to sell their oil at.”

Even at -$37 on that day, LeBlanc said, a producer planning to drill in a proven field might go ahead and drill if they had the cash in hand. Futures prices then were coming in at $30-$40, so by the time a new well could come online, it would be profitable.

The challenge was that, at $10 for the current price, the producer would have no profits in the meantime. “You get a temporary Popeye [actually Wimpy] problem of liquidity—I will gladly pay you on Tuesday for a hamburger today—which was a massive cash flow problem because money’s not coming in the door, the acid test of the business.” With no current income, few wells, no matter their promise, could be drilled.

Because the act of producing existing wells at that price is a money-losing proposition, producers began shutting them in.

As for the Russia-Saudi price war’s effect, “It aggravated the situation. What was really happening, though, was that demand was being totally obliterated by the reaction to the virus.” Demand fell by approximately 20 percent.

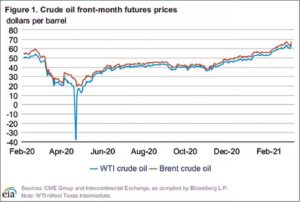

Just how big of a dip was the Big Dip? This chart from the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) gives an indication. Notice that Brent crude did not suffer the same collapse.

Demand is not “price elastic,” he noted. When oil prices go up, people still have to go to the office—and when prices are down, “nobody’s going to drive to work twice. When the price goes down, you only have marginal incremental demand come onstream.” The only thing the oil markets could do was to wait for supply to fall.

As soon as oil prices began to rise, Le Blanc noted, producers restarted many of the shut-in wells.

Matt Smith is director of commodity research for ClipperData, a global leader in cargo data. His unique perspective revolves around offshore storage, which was one of the significant issues in the price collapse.

Along with Curtis and Le Blanc, Smith sees the timing of the demand debacle coinciding with the OPEC+ price war-caused supply glut as the recipe for a price disaster, the magnitude of which would have been hard to foresee. Some of the explanation, for him, lies in the fact that oil shipped from Saudi and Russian ports doesn’t arrive at most destinations until two months later.

“The price war got going and that crude was coming across right at the peak of the demand impact of the coronavirus. So these two things combined,” he said. Many of the market-share-based price war’s extra barrels were shipped in March, before the crash, and they turned up on the U.S. coast in April through June, when demand had disappeared.

That demand drop caused U.S. inventories to hit record levels, topping at 541 million barrels for the week ending June 19, according to the USEIA. At the same time, offshore storage stranded in tankers also reached all-time records, surpassing 200 million barrels. “You were seeing [stranded tankers] in the United States, off the West Coast, you were seeing it off the Gulf coast as well. But you were also seeing it off of Singapore and other major demand hubs.”

Even though near term prices were impossibly low, Smith noted that futures prices further out were still above $40, a contango situation. So anyone who had storage space could buy low at that point and hope to sell high in a few months. The trouble was, storage, as noted, was filling up. Storage concerns were to the point that makers of any kind of tank began advertising their product as suitable for oil storage—and that jokes were made about swimming pools in Houston being employed in the same way.

Ironically, Smith believes it was a Chinese act of self-interest that solved the storage issue and restored markets to solvency. “When prices crashed, they saw this huge opportunity, so China went out and bought everything they possibly could—bargain basement crude,” taking advantage of those prices to build up their energy security.

Between May and September, “they were pulling in an average of about 10.5 million barrels a day. They actually peaked in June—they discharged 11.2 million barrels per day [into onshore storage], purely from vessels coming from all around the world.” Smith pointed out that this is just what was imported from vessels, his area of specialty. Other crude was flowing in from pipelines connected to Asian oilfields.

The Lessons

Smith:

Something like this cannot pass without lessons being learned, Smith’s top “lessons learned” include the fact that “even though the United States is much more in control of its own destiny, in terms of production, the Middle East is still that swing producer on a global basis. They have the ability to really impact prices in both directions.”

Additionally, “What happened with China, with them buying up all this crude, has just reflected the growing influence Asia has on the global markets.”

The irony here, for Smith, is that as the United States becomes less reliant on the Middle East for imports, it becomes more reliant on Asia as a destination for exports.

LeBlanc:

Should there be another COVID-19 travel ban and resulting demand drop, LeBlanc believes investors learned some valuable lessons that will prevent a recurrence. Investors who’ve “seen this movie before” would see a buying opportunity at around $10-$20. That buying activity would push prices up, avoiding another below-zero event.

Curtis:

She notes that, since the crash, the market has seen the Saudis and Russians more willing to cut production to boost prices—announcing support for prices around $50—so it would appear that market leaders have learned an important lesson about the greater importance of pricing over market share.

The price recovery after the crash, she believes, was more about market forces than a Chinese buy-in. What drove the market back into equilibrium were “the fundamentals of the market, and a gradual recovery.” During that time, she pointed out that the U.S. stock market was booming, “But oil prices got stuck in the $40 range and that reflected reality. We were only at $53 WTI prior for five years, so $40 oil, considering COVID and all that was happening around the world, was a relatively healthy price, actually.”

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

Paul Wiseman is a freelance writer in oil and gas. His email address is fittoprint414@gmail.com.