Oil and gas are changed for all time. How each company responds to those changes will determine its fortunes.

by Jesse Mullins

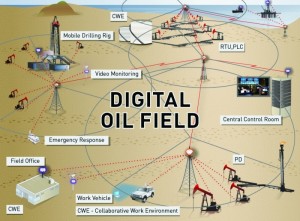

Editor’s Note: In this, Part 2 of our first-ever look at Information Technology (I.T.) as it pertains to the oilfield, we spoke with a handful of experts in the field. Technology and communications have, separately, made great strides within our industry, but together, technology and communications have linked the farthest corners of the oilfield and drawn every farflung component into a unitized whole—one that has a dynamic all its own. That change has changed the game, not just for data security (which is now more critical than ever) but for operations on the whole. It’s one world out there, and the Digital Oilfield, which is everyone’s oilfield, is connected to every single part of it, for good or ill, here or abroad.

The ripples that have gone out from the Digital Oilfield have reached some far shores—including even governmental bodies, regulatory agencies, and I.T. and cyber professionals of every imaginable persuasion. You know that the oil patch has entered the highest circles of high technology when state authorities responsible for information security statewide are speaking at oil and gas conferences.

Which is something Brian Engle was doing just a few months ago. The Chief Information Security Officer for the State of Texas was one of the speakers at the Cyber Security for Oil and Gas Conference, held in Houston in June. Increasingly, top oil and gas executives and security professionals from the Permian Basin and other oil-producing regions are making their way to these conferences to network and share strategies and learn the latest policies and procedures in an industry that is truly entering a new phase and a new age.

Engle spoke with PBOG Magazine for this report—as did Lance Tolar (an I.T. professional and consultant who heads Abilene-based Tolar Systems, Inc.) and James “Skip” Anderson, director of sales and marketing for Skycasters, a company that specializes in satellite communications. Engle pointed out just how pervasive the risk factors are, where information is concerned, and how much education is needed to close that security gap.

Engle said that as CISO for the state of Texas, his job is focused on setting the standards for oversight of security for the state agencies in the various levels of state government in Texas, which of course extends through the state’s systems of higher education. Further, his office establishes, through state law, an administrative code to execute those security standards for those organizations. But beyond that, his office has been called to reach out more into the state’s private sector.

“Additionally and somewhat recently, we’ve started to do things more in the areas outside of state government—although we’ve always had an interaction with federal government entities and law enforcement and so on,” Engle said. “But in the 83rd Legislature there were a couple of bills that modified my office’s role to perform more coordination functions throughout the state so that we would be working to improve security across the critical infrastructure and in industry.”

One of the key ingredients to that challenge, Engle said, arises from the realization—one that is supported by many statistics and facts—that the number of security professionals who are employed in the state is well under the number that would be deemed necessary if all such organizations are to have adequate information security. And because of that perceived shortfall of professionals, Engle and his peers are striving to “utilize some of the resources of our educational system in higher education to supply a greater and more capable cyber security workforce.”

Engle and others in his profession want to inculcate a sense of information security that applies from the C-Suite level on down. A newer and broader awareness of what cyber security means, and how it can be protected. He asks, “How can we do things on that level to [put more professionals into industry]? What about developing Masters programs? If you’re getting your MBA, how aware are you of information risk and the types of things that need to be thought about in an organization as you use technology to perform whatever it is you do in your business?”

Sensory Equipment

High level overviews are one thing, and practical applications are another—and to learn about some of the hands-on aspects of I.T. security, we spoke with Tolar and Anderson, two who deal with the needs of companies in West Texas and elsewhere.

Tolar, for his part, was quick to point out that information technology and automation—as time-saving and money-making as they are—are not unmixed blessings. Every company needs to stay aware that the deeper they move into technological solutions in the oilfield, the more they need to be aware of what they are leaving behind, some of which was good.

“What I’m trying to get people to understand,” Tolar said, “is that you can’t just pull the human out and plug the technology in and expect everything to go perfectly, without any side-effects. Because humans aren’t digital, and digital equipment isn’t human. There are some components there that bring you gains, but there is also the loss of some ingredients. You have to strategically understand what you’re gaining and what you’re losing so that the net effect is that your information is accurate and actionable. That’s when companies are going to succeed and grow—it’s when they have dependable, accurate information.

“It’s as simple as that, and it’s also as complex as that,” he added. “Sellers of technology often will come to a prospective buyer and say, ‘Hey, here’s this magic bullet, or here’s this magic widget that’s just going to make everything better.’ And then the buyer implements the technology, but it’s not part of an overall strategy—it’s just a ‘fix’—and then the company finds that its people can’t make that solution work. The answer has to be a team effort, and the technology has to be a part of the team. The technology is a personality. It needs to be thought of as a team member, almost as an employee. It has a job to do. It needs to have a place at the table. It needs a support system—it requires the proper environment to be placed in, the proper air conditioning, backup systems, and other components. And it needs to be able to interface with the other systems in place and to be able to do a job. A job that must be done daily.”

It helps to develop that mindset, Tolar said. It helps to begin to think of technology not just as a tool but as an individual. “You have to learn to listen to it,” he said. “It’s communicating with you, but you have to learn its language.”

He compared that kind of language, that kind of familiarity, with the familiarity that a pumper or an engineer would have with the field equipment he oversees or maintains.

“These experienced hands, they can go into out to an oil site and they can just look at things and say, ‘Hey, that pump over there sounds funny.’ Or they can go to the next oil site, and they’ll say, ‘Well, that hardware always sounds like that. That’s just the way that one sounds.’ These veteran oilmen, they instinctively know these things. Now, you put a meter out there, and all of all of a sudden things start breaking down. And then you wonder, ‘Well how did that happen? It’s all because that old pro had this vast information. He can just go out there and, almost by merely noticing the way the wind is blowing, and the smells that he smells, that something’s not right. Something doesn’t smell right, or feel right, or look right. It’s difficult to put a sensor out there to do that. That’s what I call ‘body language.’ [See sidebar for more on “body language” and “The Human Quotient”] Those professionals are just ingesting all this information with all their senses.”

Tolar’s point, then, is that companies need to be aware of not just the capabilities of technology, but the limitations of technology, and they need to factor that awareness into their overall thinking. And further, in “listening” to their technological solutions, they need to listen for the data that is not there, just as they must heed the data that is there.

Doing Business in Real Time

Besides data and automation, there is communication, and that is often the unacknowledged third leg of the Digital Oilfield—a leg without which it could not stand. James “Skip” Anderson, of Skycasters, deals in that reality every day. For Anderson and his peers, the oilfield has become the bigger part of what they do.

“It is now by far our biggest business segment,” said Anderson. “I would say a good 50 percent of our business right now is growth in the oil and gas market. Whether it is the actual drillers, the suppliers, the service industries, or whoever. It’s where our growth is strongest.

Skycasters does business across North America, including Canada and Central America and the Caribbean, but the Permian Basin is, as far as Skycasters’ business is concerned, as big of an oil play as they serve.

And it doesn’t matter where on the continent the oilfield is, it’s generally in a “remote” location.

“These oilfields are in the middle of nowhere,” Anderson said. “And they’re able to put these rigs up so quickly that there’s no infrastructure. There is no phone lines, there’s no fiber connection, there’s no cable. In order for them to do their jobs properly they have to communicate on an ongoing basis, not just verbally, but also through data streams they’re sending back to their headquarters. That’s where we come in. In the old days, they’d be writing down notes, and maybe at the end of the day they’d call them in. Or once a week they’d send them in. Now, it’s real-time data that they’re dispatching, so they can inform the geologists back in the office or the head guys, wherever they’re at. And they’re getting replies back, saying, “Okay, change your drill speed, angle right, angle left, change out the drill bits.” They can do all of that in real time even if they don’t have local infrastructure. [That is, they can do so with satellite communications.] This speeds up their drilling process.”

Does that also mean that an operating company can take one geologist or engineer and utilize him on more than one rig as far as decision making is concerned?

“That’s the way we’ve always understood it from some of our larger customers,” Anderson said. “It iss easier for one geologist to be in headquarters and receive multiple data streams from different rigs. That doesn’t mean that they may not want one on site, depending on the type of drilling they’re doing.”

And there’s more to it than that.

“You’ve also got monitors that are looking at pressure, that are looking at gases that are being discharged. And they’re monitoring the frac’ing tanks. They’re monitoring all kinds of equipment and that’s all in real time, so if there’s going to be a maintenance issue a lot of the sensors can pick that stuff up and it can be transmitted. So, the next thing you know, maintenance crews are showing up without even being called.

“It’s all because of this constant data. If the oil company has a good internet connection through fiber or cable or phone, then in that case we’re sort of a last resort.”

But even then—even when thought of as a “last resort,”—the satellite connection is critical. Why? “Because we’re a backup for their critical systems,” Anderson said. “There are some things that you just don’t want to go off-line, ever.”

On some of these big frac jobs, the clock is ticking, and the meter is running, and the rate is high. Very high.

“In some cases the costs are $10,000 an hour to have some of this equipment sitting out there and when it’s not producing or it’s not working they’re still paying them,” Anderson said. “You just don’t want to have to shut those operations down.”

Moreover, there is a human connection that shouldn’t be undervalued.

“A lot of these guys are on these rigs in the middle of nowhere for weeks at a time, and we [Skycasters] are an internet site, so really they can touch base with their family via email or video calls or face-timing on their phones. If they’re somewhere where there’s no data or no cellular service they can use the internet, through the satellite, to provide this service.”

Commenting on the roles that companies such as Skycasters play, Lance Tolar remarked that the connections speed up all processes, and there are many processes going on simultaneously on a large drilling site.

“Companies like Skycasters provide the technology so that a geologist can sit in Midland, Texas, or Houston, Texas, or wherever,” Tolar said. “It’s the same technology that radiologists use and doctors use to examine x-rays from a patient that may be in Mexico City. Today it’s not necessary for a hospital to overnight those x-rays or overnight those MRI results. The doctor can look at it right there in real time. In the same way, a pumper, sitting in an office, can look at that monitoring system across the country just as easy as he can if he’s staying in a trailer on site. That’s where the real benefit where digital technology is. That’s the benefit of the digital technology—it’s in being able to transport that information anywhere almost instantly, and being able to utilize people across greater geographical areas. A company like Skycasters can say, ‘I don’t care what you want to do. You want to do voice, data, or video? We can do it in South America. In the middle of the jungle.’ There is no issue with that. That’s a benefit, and you can leave our equipment there, and it’ll work.”

Conferencing to Stay Informed

Engle, asked about the benefits of conferencing on the topic of cyber security, said one benefit for oil and gas professionals is that it exposes them to some actionable steps they can take when they get back to the home office.

“Sometimes it’s a chance to encounter those people whom you don’t normally see or whom you haven’t met before,” he said. “That exchange of business cards can be really important because it gives the opportunity to bounce something off of somebody later or to develop that peer relationship that is quite frankly very, very necessary in this environment. If we were all left to make it all up on our own, we would struggle mightily. Where we can interact and collaborate with each other we have a much, much better chance of putting in things that are going to be resilient, things that can answer what we’re facing.”